June 2023

Ohyescoolgreat

︎︎︎Published in The Plant #19

Years, moment, Ohyescoolgreat

*

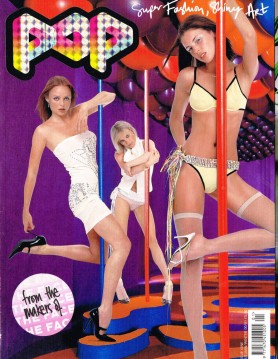

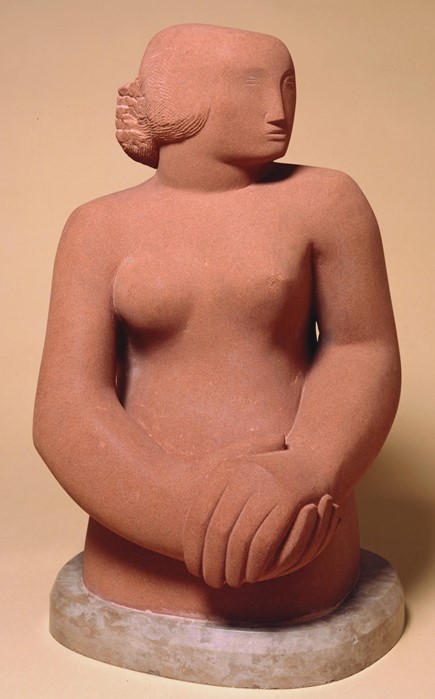

Bless N°05 is not a product - it is an opportunity.

It is an invitation from BLESS to customers with a critical outlook on taste and fashion. The BLESS N° 05 is a test of the conviction of BLESS customers to the fashion form that BLESS pioneers. It gives the chance through investment into the future design of BLESS to prove relevance of trust and the faith of customers. Here is the chance to participate in the creation of a new phase of design and to enable the development of new products. The goal is to achieve a partnership with customers which enables both parties to feel a sense of achievement at each new product that is created through this process. The pre-financing through subscription helps BLESS maintain it's freedom. Through this freedom one can concentrate on the essentials. The customer also benefits from this new interpretation of the coulture idea in the meaning of a special service. The offer is strictly limited and intentionally so to allow direct contact with the participating members to encourage and contribute to the interaction between BLESS and it's customers. The offer is a purchasable right to be part of the "trust partnership" and is valid for one year. This entitles the member to certain inalienable rights which are: • Special services, as i.e. the choice of a personel limited-number. • Exclusive delivery (before the general public) • Special conditions for the BLESS advanced line and other special products • Cost savings on BLESS products • Laid back consumption __ The cost od participating in the BLESS "trust partnership" is DM 1000.-, which means to receive the next 4 BLESS products free. __ subscribe BLESS / abonnez- BLESS / abonniere BLESS / pay once 1000,- DM and get the next 4 BLESS products, relax for 1 year. For subscribtions call: BLESS Paris +33 1 48 01 67 43 • BLESS Berlin +49 30 44 01 01 00 • BLESS GbR Kaag/Heiss ∞ Oderberger Strasse 60, 10435 Berlin, Germany * Bankverbindung/ Relation banquaire/ Bank Account: BLESS GbR Kaag / Heiss ™ Dresdener Bank, Berlin (Bereich 262) • BLZ / Code etablissement: 120 800 00 • Konto / Numero de compte: 40 486 036 00 M•&-**/ FOR INFORMATIONS CALL: PRESS PARIS +33-1-42 01 5100 • pressing@wanadoo.fr • PRESS MILANO +39-02-58 10 55 20 • fsoncini@planet.it www.bless-service.de blessparis@wanadoo.fr blessberlin@csi.com

- BLESS N°05 Subscribe BLESS (1998)

BLESS is best explored as a speculative project for a different kind of fashion making. The creative platform established 26 years ago by designers Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag sits directly within (or outside of) all of the creative disciplines and resists formal categorisation. BLESS products are rigorous, fantastic, poetic, spiritual and sometimes, joyfully odd.

Formally trained in fashion, both Heiss and Kaag were suspicious of the discipline’s glittery veneer from the start. The period in which they met – the early 1990s – felt like a particularly free time for young designers and artists. Despite an underlying sense of both climate and political crises, things seemed possible. In fashion, the left shoulder on a two-button jacket could be yanked up 10 inches and it would be accepted; a skirt could become an object for the home. Upcycling army surplus was pragmatic, not profound. A transgressive naiveté flourished and as a result “the nineties” have become shorthand for bold ideas previously uncomplicated by the engulfing scale of the internet. Today, even the rambunctious pseudo-intellectual silhouettes of Rei Kawakubo have been flattened into little more than bejewelled seasonal blips. The very notion of being – let alone surviving as – a ‘conceptual fashion designer’ has been erased with every software update.

Demimoorebag, life, wondered

Despite BLESS not being underground nor unknown, it feels like a challenge to try and get to know what it is or who Heiss and Kaag are. They have enjoyed a level of personal anonymity that is difficult to imagine in our byzantine digital age. Early on they refused to have their portraits taken, which Heiss says was ‘almost like an educational statement to explain that the core of our work is not about us as people. It's really about what we want to say with our products.’ After releasing a series of accessories, their first full clothing collection – BLESS N°09 Merchandising – was offered in 1999 as an answer to the dilemma of persisting press requests for portraits of the designers and included t-shirts with their pictures on. Two years ago they decided to make a new product-cum-portrait, this time creating a handloom jacquard of their merged faces. ‘Supposedly, BLESS is a child – now of 26 years old – which is a great age,’ Kaag says. ‘This is BLESS today.’

When the pair first met in 1993 at an international competition in Paris they had not been used to the rhythm and demands of creative collaboration. Heiss, studying at Hochschule für Angewandte Kunst in Vienna, navigated the English eccentricity of guest professor Vivienne Westwood with the sensual rigour of Helmut Lang and later costume designer Frida Parmeggiani. Kaag meanwhile spent her time at Fachhochschule für Kunst und Design in Hanover exploring what ‘innovation’ meant within the context of fashion. They were immediately drawn to the handcrafted alchemy of each other’s work: Heiss using crochet and Kaag felt.

They kept in touch and worked on an edition of 20 sheer summer tops in 1995. They spread posters around Vienna and Berlin of collaged women wearing them with only the name BLESS and a telephone number underneath. Soon after, using money borrowed from their parents, they placed ads in i-D, Self Service and Purple Fashion listing the same number next to a Polaroid of the first BLESS product: a fur wig. Martin Margiela commissioned the duo to make more out of old fur coats for his A/W 1997 show. BLESS’s creative output was – and is – fuelled by a kind of rational naiveté.

When they first had the idea to collaborate, they penned a manifesto:

‘BLESS is a visionary substitute to make the near future worth living for. She is an outspoken female – more woman than girl. She’s not a chosen beauty, but doesn’t go unnoticed. Without a definite age she could be more between her mid twenties and forties. B. hangs around with a special style of man. She has no nationality and thinks that sport is quite nice. She’s always attracted by temptations and loves change. She lives right now and her surroundings are charged by her presence. She tends to be future orientated.

BLESS is a project that presents ideal and artistic values by products to the public.’

In the same way we try to give bodies to the chatbots and A.I. machines intruding on our lives today, BLESS was personified as the ideal woman of the 1990s. A free spirited and open minded, confident somebody. Heiss and Kaag knowingly created an avatar to protect themselves from the disturbance of celebrity. ‘When 10 years had passed, we were reflecting on that manifesto and asking if it was still valid. We thought that as we were older, we wouldn’t have done it in the same way but now, after another 10 years has passed, it somehow feels valid again,’ Kaag says.

‘When we started to work together, the urge to define who we are and what we have in common was important and that's when this character appeared,’ Heiss says. ‘The manifesto talks about things that were dear to us and also some wishful thinking… how we would like to be. It was not intended to be the starting point for the outside, it was the starting point for us, to understand what we were. We wanted to establish our own values and invent a world – and everyday life – that we could live.’

These values were designed to negate certain norms. Heiss and Kaag call what they do a ‘made-to-measure profession’, it is something that they have grown with and into. Whose needs would they serve? How would they make money and survive? BLESS was ‘a pot where you could put in wishes for a better future’. They were realistic in what they did not want. Kaag says: ‘Observing what’s happening today, young people in general tend to dream for bigger things but it's very rare that people take the time to sketch out a schedule for the week or for the year on how you would like to live and work. This is something we did in a very playful way in the beginning, wanting to take the time to think about a product and then release it the moment it was finished.’ Yet quickly it became apparent that the structure of the industry – its seasons – helped to formalise their way of working rather than hinder it. ‘It took me years to really accept that the seasonal rhythm made more sense for us, but this was good because otherwise we would have been far too slow’ Kaag says.

Armpitshirt, thought, feel

Too easily BLESS can seem like an esoteric post-modernist charade. A wooden hairbrush which has flowing locks of human hair in place of bristles is not an inert Surrealist object but rather a tool whose purpose is to preserve hair as a souvenir, a practice associated with Victorian mourning traditions. Chairs designed for BLESS N°07 Living-Room Conquerers (1999) on which denim or cotton-Lycra is held taut by tall fiberglass sticks maintain their functionality despite looking entirely new. Since 2005 Heiss and Kaag have continued to transform the appearance of the electronic cords, cables, and chargers omnipresent in all our homes by threading them with wooden beads, artificial stones and plastic bangles. ‘There was always this questioning of “is this a good idea?”’ Kaag says. ‘That’s why we started to develop all these side activities and this dilettantism to work with things that we didn’t know. This is something we are proud of, more than having a certain career in interior design or fashion or whatever. What has not changed over these 26 years is that we are better in doing things than talking about them.’

The duo are impressed by the sheer fact that they still exist. The complexity of creative thinking which BLESS has applied to everything from their retail spaces (a residential flat in East Berlin) to the things they make has established a new way of contributing to the worlds of fashion, art, interior design and philosophy. ‘There has been no recipe or even anything we wanted to transmit but we’re so lucky that we’ve found the glimpse of how life could work for us,’ Heiss says. ‘If you take your own values and your own needs as a base for whatever you create, it's necessarily meaningful. It's not hollow. And it's also tough in a way because of course, you fail permanently.’ The duo have always approached BLESS as an ongoing research project that will eventually come to an end.

Important, understand, point

Presently Heiss and Kaag are working on their third printed volume Celebrating 25 Years of Always Stress with BLESS N°42 – N°74 which will be released this summer. Like the two books before it (Celebrating Ten Years of Themelessness: N°00 – No°29 (2006) and Retroperspective Home N°30 – N°41 (2010) published by Sternberg Press) the book brings together their archive alongside illustrations, photography and special projects. BLESS’s relationship to its archive is pragmatic. Since the start Heiss and Kaag have numbered their projects, so it is easy to follow the thread of each idea and trace how they connect. The rhythm of the fashion cycle and life’s changing moods reveal themselves via BLESS’s interventions. The concerns of today – the climate crisis, the fashion system, consumerism, capitalism, individualism, and collaborative networks – are present throughout their archives. Their work – no matter how strange or fantastic – pulsates with a contented, benevolent rigour whether presented within the halls of an international museum or at a child’s 7th birthday party.

The manifesto composed at the conception of BLESS has changed in meaning and relevance with each passing decade – as they approach a third, their ‘more woman than girl’ has aged. She has in some ways become more formal, more complete. So what are her interests now? Kaag says: ‘it has entirely changed but on the other hand, I am still questioning the same things.’ Perhaps then it is not about how things change but how they evolve. ‘When we did the first book, I can remember that the reactions to our things were not really that great but then, 10-15 years later, people come and say “Oh, it was so fantastic what you did back then!” and like with every year you evolve, of course you can build on that corpus that you created. It gives more density,’ Heiss says. ‘I have the feeling what we do now is more consistent. We can work with stuff retrospectively; we can feel inspired by our own products and do new versions using a vocabulary that we have created. We salute a kind of pragmatic, troubleshooting kind of creativity that has to serve a need.’

This term “creativity” is a contentious one today, splattered liberally across the western world as a kind of big blue pill for happiness. There’s a common misunderstanding that “creativity” stands for freedom and leisure time. ‘It's extremely boring,’ Kaag says. ‘You must be creative to run a business, maybe more than to decide if a jacket should be red or blue or in leather or whatever – that is not the creativity that we need. Creativity is more about how to survive in a world without losing patience.’

A/W 2022

Now, Now.

︎︎︎Published in Ima Japan Vol.38

Now, Now.

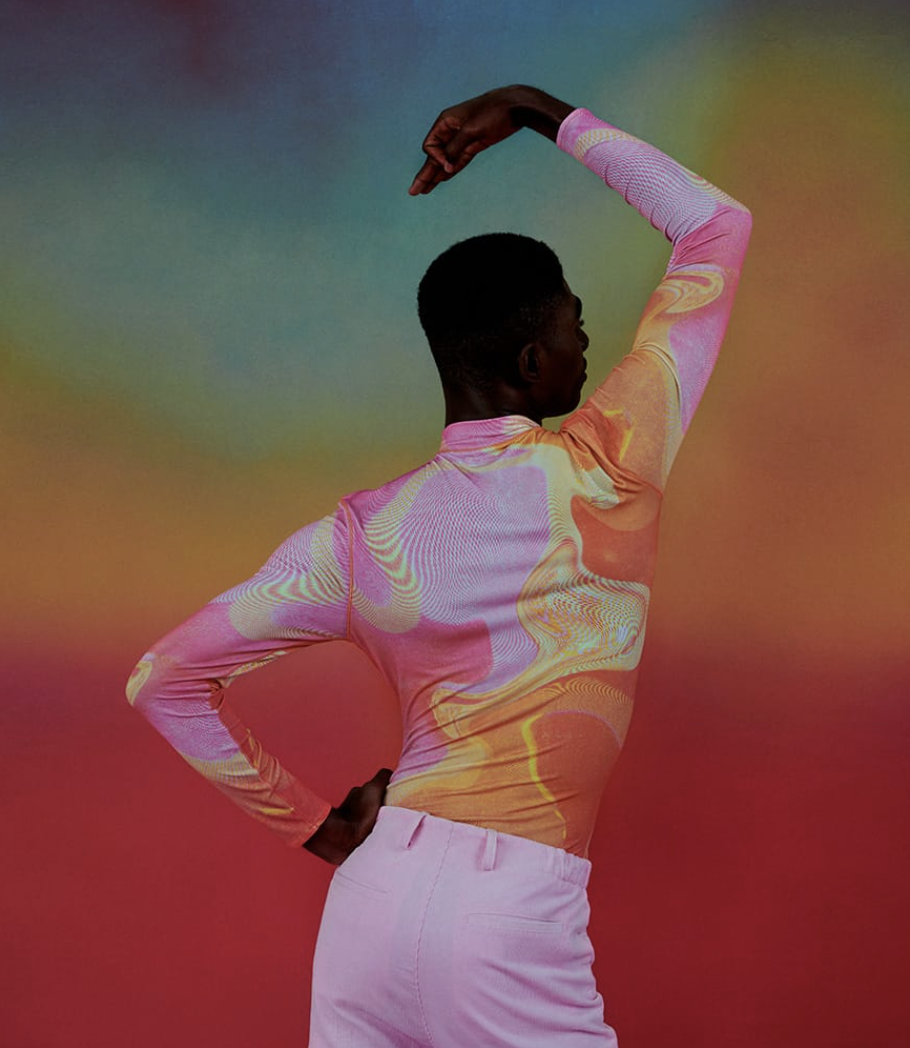

Is it the pose that makes a fashion picture? Maybe it is the make-up and hair and nails? Is it defined by the texture of a pavement or the colour of a wall? Is it about the clothes? The works presented here by Hugo Comte, Thomas Albdorf, Feng Li, Valeria Herklotz, John Yuyi, Campbell Addy and Jet Swan are technically fashion pictures because they have been made mostly for the commercial context of a magazine, billboard or advertisement, yet there is something else going on. On their own, either yanked from the spine of a magazine, or as they are here (single jpegs on a screen), these pictures perform in a different way. They exist as fragments of an attitude. A frame of mind.

Fashion is a strange mix of nostalgia and impertinence. The conventional belief that a fashion photographer’s trade is to freezeframe a buzzy moment into something that will only last a single month has become undone in an age where all pictures outlast their welcome. They don’t go away when a billboard is replaced, or a magazine trashed; they languish online forever. And so, in reaction to this permanence, the creative generation making work today unanimously try to avoid the uncomplicated label of “fashion photographer” – instead preferring looser, more ambiguous terms like “artist” or “image maker.” The disciplines of fine art, creative direction, graphic design, sculpture and photography have collided to form a more changeable discipline. The business of making pictures takes more than the click of a button.

Hugo Comte studied architecture in Paris before pursuing photography. He dedicated months to researching fashion editorials from the 1980s and 1990s to understand what had been made before him. As a result his own glossy work channels a kind of nostalgic hero-worship; its composition, lighting and attitude is from a previous epoch. The closeness of Comte’s pictures to the iconic body of work produced by Steven Meisel between 1996-2001 makes them almost pastiche, except, Comte’s is so tightly observed that they trick the modern eye. Comte refers to himself as an “image-maker” rather than “photographer”—his influence presides over all aspects of the image, not just the final frame we see.

Berlin-based Valeria Herklotz makes photographs that are informed by her previous experience as a model scout. Her work is discussed, introduced and framed more as portraiture than straight photography. The Chengdu-based Feng Li was—or perhaps still is—a “street photographer” and more recently has become a “fashion photographer”. What it means to become a fashion photographer is a topic of discussion that more editors and photographers should be asking themselves. The South-London born Campbell Addy is a “photographer and filmmaker” but his richly toned work, focused often somewhere between the Black body, cultural identity and queerness, feels also like a political and curatorial act. He told British Vogue that his “culture” is a “hyphen.”

After working for several years as a Graphic Designer and Art Director, Vienna-based Thomas Albdorf’s photographic sculptures—mainly still life—take their inspiration from artists Fischli & Weiss, Roman Signer and Koki Tanaka. They bring together attitudes and processes previously reserved for the art gallery. If you were to ask him, Albdorf is simply an “artist”. The Taiwanese Chiang Yu-yi (who is known professionally under the moniker John Yuyi) is a “visual artist”. The British-based Jet Swan is modestly a “photographer.”

There has been a redefinition of the term fashion photographer to something more elastic, which suggests that photography—and more specifically fashion photography—has become too narrow a term. There is an invisible line between the function of Albdorf’s absurdist and surreal constructions deployed to sell handbags and shoes and purses and their formal conceptual contexts for example. Born in Linz, Upper Austria, Albdorf studied Transmedia Art and so has been focused on the contemporary status quo of the photographic image and the decontextualization triggered by internet distribution.

John Yuyi’s work is shaped by the internet too—it is a kind of revulsion of her own online addiction. A pre-or maybe post-internet attitude shapes her pictures that are layered and memeable. They involve human skin in a way that goes beyond make-up—there is a sense of collaboration and commodification as faces and bodies appear in the pictures more than once. They are refracted and replayed in a number of ways. Her practice explores aspects of social media, and her own hefty online presence.

The process of making pictures has been changed by how we now live our lives online, but how has it changed their content? In Comte’s work, the internet influences a knowledge of the archive and what has come before. Often, Comte’s photos look like they are from the 1990s when they flick up on Instagram. Herein lies their appeal—they are familiar, comfortable. They maintain the hierarchy of glamour and grunge and sleaze that so much of contemporary fashion photography is based upon. “90s images really express an energy more than anything; some eras it’s about style or concept, but this specific era was about expressing a human energy,” Comte told i-D in 2020. His photos have a metallic din, skin is very precise in texture that it is almost cyborgian. His photos reflect the glow of the screen; faces are lit with a gentle radiance.

Valeria Herklotz makes pictures that feel like today in part due to their vivacity, energy and simplicity. The women in her pictures are often young and caught mid-pose. They are de-glamourised. Her taste in clothes—which is something we need to always remember when looking at fashion photography—is dishevelled, layered, not quite right. With her work she is tugging at traditions of portraiture.

Location is central to the fashion image. When we leave the safety and anonymity of the studio and take to the streets, we can more easily capture a clearer sense of time. Based in the Chinese city of Chengdu, Feng Li’s work takes a more playful, less Eurocentric idea of beauty and has some fun with it. His pictures have life and vigour. Fashion photographs made in Europe that claim to be inspired by movement often feel very still, very posed. Li’s photos are wild with smiles, arms flying, feet askew. They radiate a happy, idiosyncratic charm. The clothes he shoots are extreme too and are given equal status in the gestures of the models. They get the performance they deserve.

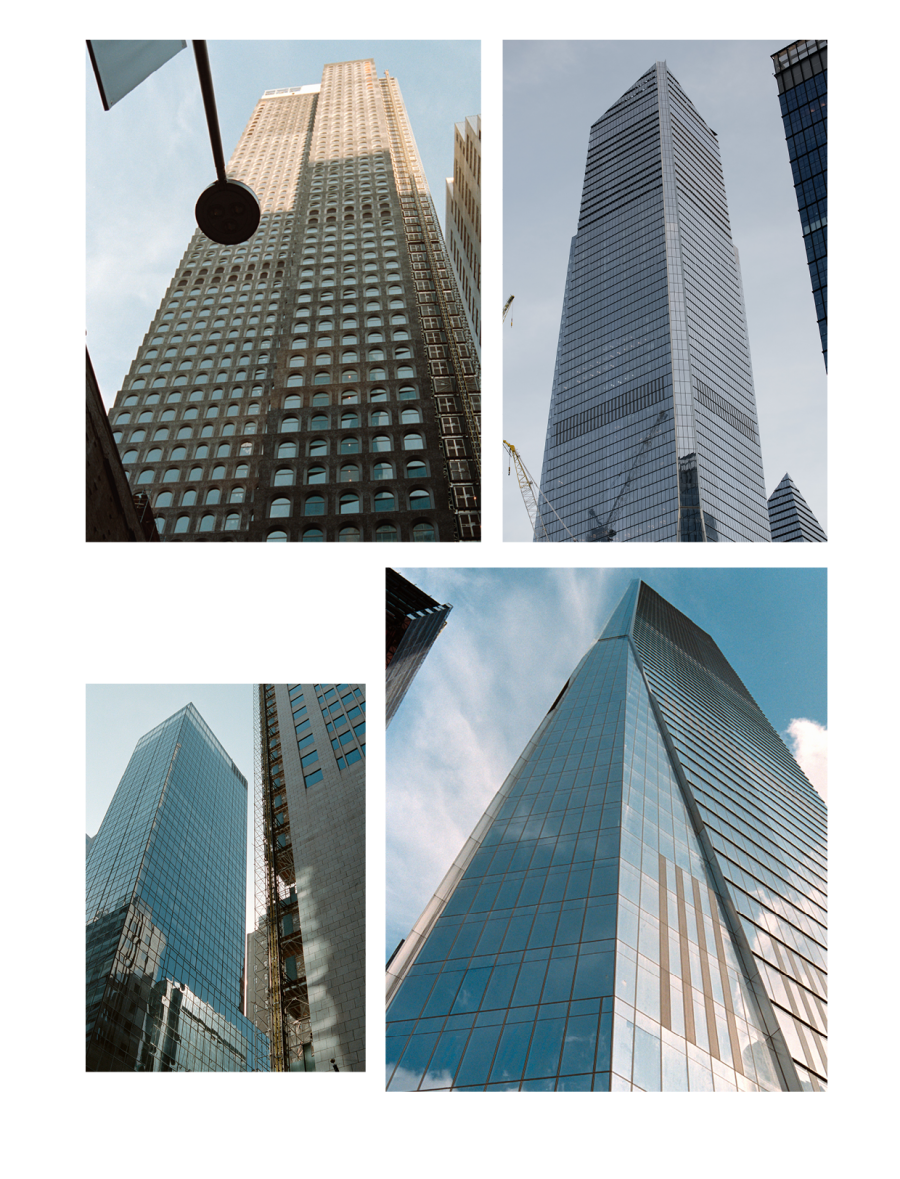

That Li began as a street photographer is key to his practice and approach. He took up photography in 1996 before securing a civil service job working as a photographer for the Sichuan provincial department of communication. That job involved photographing technological hubs, high tech factories, and CEOs. His fashion work needed to be the antithesis of this, for his own sanity.

I have been thinking about which of these images look like now. This is an absurd feat but nevertheless it is the primary function that fashion pictures need to serve. Campbell Addy’s lens always seems to luxuriate in their subjects; women and men are strong and bathed in colour and light. Addy’s work borrows the classism of the 1950s studio setting but jolts it into the now with an unabashed reverence for queer glamour.

Jet Swan’s body of work has a perversity to it that feels like it could only exist today too. There is always something off or surreal or ugly in her pictures which seems to puncture any preconceptions we have about a woman making pictures that are adjunct to or informed by fashion. Swan’s debut monograph Material gathered together three years’ worth of photographs and portraits she had made of strangers. A lot of her subjects are rarely identifiable; their heads cut off and their bodies exposed. There is a rawness in the work that is confrontational. She presents the female body in its truest and most multifaceted way. Never airbrushed perfect, in fact, Swan seems to highlight the bumpiness of skin, the outline of the body, the push and pull of veins.

Her pictures prove that to us that any sort of demarcation between the disciplines of fine art and fashion photography is futile. What we need to consider is the content of all of these pictures and what they might tell us about fashion today. In Swan’s work, we are perhaps over fashion, drained by its excesses, its lies, its fantasies. Her work seems to feel like now because it is grounded in an inky, earthy truth.

January 2023

Today's Self-Portrait

︎︎︎Published in Encens N°49

Today's Self-Portrait

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

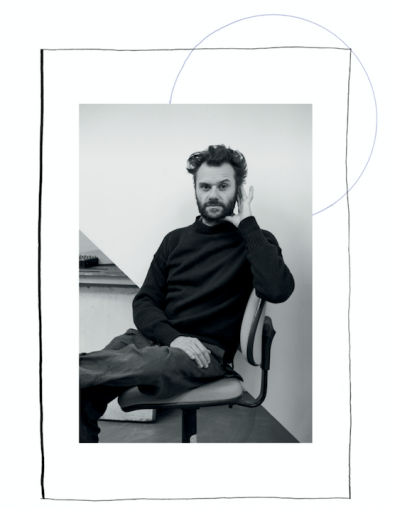

Dal Chodha: Most of your life – your creative life – you have been in London and New York. Today you are working inside of a 400-year-old well in the Spanish countryside. You live in the same village as six generations of your family in a house that is 770 years old. How has your perspective changed now that you are based where you are?

Miguel Adrover: I’m really aware of what is going on in the planet but, yes, for a little while I stepped out of it because I found it really overwhelming. A lot of my work is dedicated to this kind of awareness and for a long time, fashion was the only way I could do, or at least say something. Ten years ago we could see the Amazon burning but if you mentioned it, people thought you were crazy. But that is the life of an activist. For many years I was considered toxic… but what I was talking about is being embraced by everyone now.

DC: The appropriation of logos, repurposing deadstock fabrics, re-thinking the two-season norm, questioning corporate power – you did all of this two decades ago with your collections. You’ve said that your studies were much more geopolitical.

MA: Exactly. Now, being here, I’ve had the opportunity to watch the world through a window and not participate in it. I can see it all happening again and young people don’t even know who I am. They think that they’re the first to use fashion in this way.

DC: What you were doing – what you are still doing through your photography and self-portraiture – is so vital, carnal, tribal, powerful. Is that why you were considered toxic?

MA: In the three appointments I had for corporate companies, that’s what I was always told. I was totally freaked out because that was the opposite of what I was doing. I was trying to get people to look up and see how unsustainable everything had become. The industry is still working in the same context. I would love to have a show in New York and express all of the division in the country but these days it’s dangerous because there’s a lot of censorship. Even from young people who can label you as “racist” and “homophobic” because they don't know what you have done before. That happened to me because of something I posted on Instagram, and I was so shocked, like WTF? I buried so many of my best friends when I was 20 years old, they were all dying because of Aids, and here these kids are calling me these awful names. I felt so much freer to say things 30 years ago.

DC: The generational differences are very nuanced and for sure, very complicated. Many young fashion followers share images of your collections – they know of your clothes, but they continually extract them from their contexts. Do you feel protected from some of these cultural shifts because of where you are? It is difficult to maintain a healthy perspective if you are in a city like New York, in the thick of it all.

MA: In truth, I am in total isolation. I don’t have a social life. I don’t even have friends. I opened this window on Instagram two years ago because I was so full of things that I needed to drop. My assistant Constanza had the page already, but I did not do anything with it because I didn’t have a mobile phone – I haven’t had one for 9 years now. I don’t experience the world through a screen on a phone. Going back to your question and how I feel here, people in the countryside are more conservative and it is the women, my mum for example, who run things. They are in control. Seeing all the stories around the #metoo movement made me think about my shows because I always presented women in spaces often only occupied by men. I did sartorial tailoring for spring/summer 2001 and everyone thought they were all lesbians! I cannot be more feminist than what I have been in my work. Throughout my life I have fought for equality; I was in Washington, I got beat up, spat at, insulted. I dropped out of school when I was 12 but ended up in London the early 1980s. I was on the Kings Road, I met Leigh Bowery, I used to go to Taboo with Michael Clark, Blitz. I studied; I was a goth. I grew up in London. The first designers I knew were BodyMap – they were so influential on everything, and no one is talking about them today. There should be a monument to them.

DC: That was a period that was about collaboration: art, music, performance – it was avant-garde. Some people think we are coming back to that.

MA: These days we don’t know what avant-garde is. Back then it was about being a modern person. It was not about selling. I used to come back to Majorca and DJ and in between that, I worked with my mum and dad on collecting almonds on their farm. I’ve always been between worlds.

DC: Now you're between worlds again because you have this Instagram presence, but you don't have a phone. You work methodically on studied self-portraits totally on your own. You express the tensions and joy of the world through a single picture that you share online to thousands of strangers.

MA: I work really hard on those pictures, and they are based on my mood but then I can change mood many times during the day. I can go for weeks without seeing anybody besides my mum and dad because I work underground – when I close that door, the world disappears. It’s only my imagination and my creativity. I have got to find something between walking from home to the well to work with, a piece of plastic I find, or a stone. Anything.

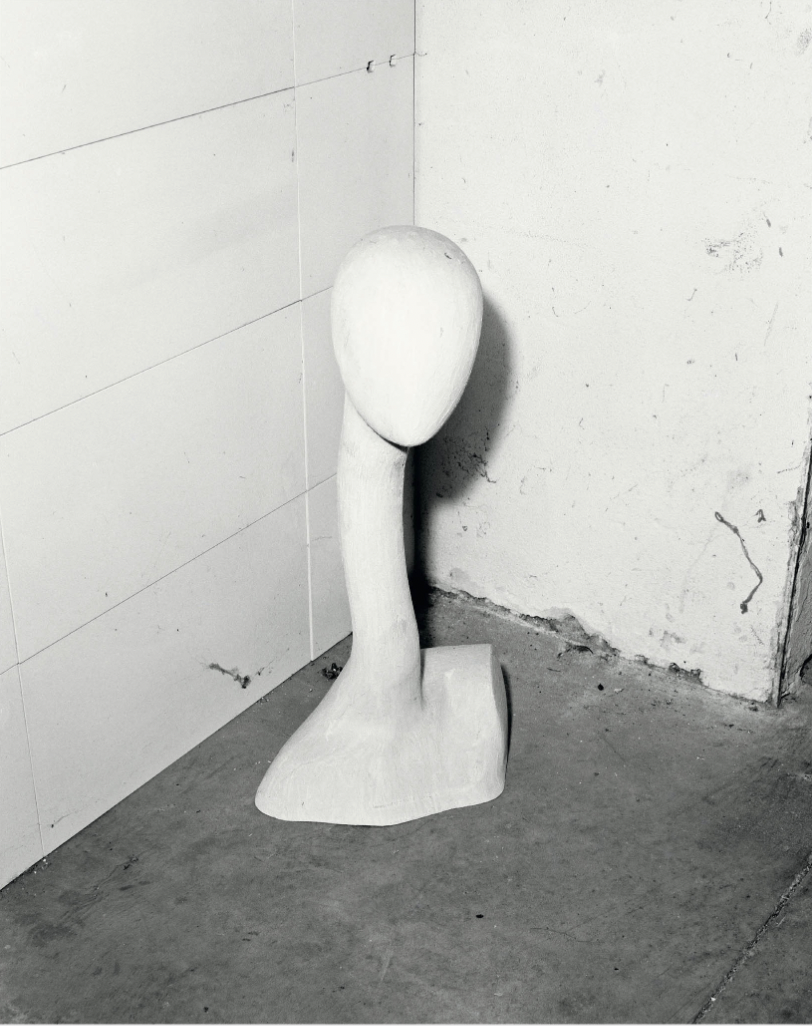

DC: In a lot of your earlier pictures you used mannequins rather than shooting yourself?

MA: Yes, I have about 20 of them and over seven years I have made about 300 pictures with them. I was going through a lot of stuff, I stopped drinking and taking drugs. I realised it was not working for me here in the village, it was okay in New York, it was okay in the middle of the stress of everything, but here it wasn’t great. My two friends were Patrón and Jose Cuervo and they were bad bitches to hang out with. So, I thought, forget it. All that energy I got through alcohol I expressed it through the mannequins. I created these big installations making my own universe, using the things around here, my grandma’s tablecloth, feathers from animals being killed for food, my communion clothes. I am 57 years old, and I have always collected stuff, so I have a lot to work with. The mannequins express a number of emotions that I think we (humans) have lost.

DC: A lot of these tableaus take on the look of classic fashion pictures – they are very theatrical and dramatic in a Steven Meisel kind of way.

MA: When I was with Lee McQueen, I had the opportunity to work with Katy England on styling with a lot of photographers like Meisel, Steven Klein and Richard Avedon. Now I don't have any assistants, and I don’t spend any money. Even on lighting because the only thing I have in the well is this little window – that’s the only light I use. It is a light that is invited into darkness. The pictures have this feeling of 18th century paintings because the light comes from the top and I am at the bottom of the frame. The self-portraits happen because I never go out. I used to be a New Romantic and, in those days, it was more exciting to dress up in your room with your friends than it was to actually go out! This energy I have inside me has to come out and it does in these pictures. When I am homesick for New York, and London I dress up like a New Romantic. I’m not dressing up for anyone but myself.

DC: What's your intention with your self-portraits? Why are you sharing them with us?

MA: That's a very good question because I'm giving it away for free. Miguel Adrover is not about selling product – this is a campaign for myself that I don’t get anything out of. It poses questions, which is more powerful than selling something because it is true. I’m connected to actuality – to what happens today. I'm not inspired by old Hollywood movies, I’m inspired by what's going on in Somalia, or Sudan or London. That’s why I don’t really understand these old houses like Balenciaga making what they do today. We have this big corporate monopoly controlling the industry that is brainwashing young minds. We're not progressing. Fashion – if we want to take it to another level – needs to take that risk of letting things die because new blood is there, waiting.

DC: Did you work with stylists when you were in New York?

MA: I worked with Eric Daman who had a fantastic American knowledge of style – and that was important for me. I was really clear with what I wanted but I knew I was in safe hands. The energy at my shows was so crazy – I remember before they would start there would be around 500 people chanting backstage – the camaraderie was so intense. And the models were all representing something bigger than themselves, they’d come from Sudan for castings for Tommy or Ralph and then wouldn’t get booked, but we’d use them. It was inclusive and representation was important. Back then designers would use only one or two black girls in a show to be politically correct, but we didn’t think like that. I really felt like the king of the underdogs.

DC: Do you still feel like an underdog?

MA: I do, but also a lot of the people now working as I was are my babies. And they should know who their mother is. It’s important that we know history – I’m not into removing things, we cannot sanitise the planet and our culture. I believe we need to confront and somehow live with what we don't like. It’s dangerous when you want to eliminate everything because then it is too easy to forget what you are fighting for. I’m part of a past. New generations need to be aware that somebody was already fighting for things, and they never did it for money. The last time I sold a collection was probably when I was creative director at Hessnatur around 2008. I remember Vogue writing at the time of my appointment that it was like hiring Amy Winehouse as lead in a church choir.

DC: I’m interested in what you said about “removing” yourself. After your last show in New York in 2012, did you consciously feel like you had taken yourself out of fashion or was it just a consequence of your beliefs?

MA: I invested everything in fashion and I never got anything back. That show, which was called Out of My Mind, wasn’t done for sales. It was the first show I did after stopping in 2004. I made the clothes out of garments I had collected from wealthy women in Palma. I’d meet them at their houses and sit in a cupboard and ask them to put all the garments that they liked on a rack. I made new clothes from their existing wardrobes. It wasn’t recycling; it was much more than that. I’m always interested in the soul inside the clothes. I haven’t been selling anything for a long time but this kind of detachment from the fashion industry happened naturally. I was really tired of having a team, of my own dependence on them and my accountability for their salaries. A lot of young people want to have a career in fashion, but it is not the same as when I used to go to London and help Lee. I used to be there for a month sleeping under the cutting tables, or a lot of the time being sent to his house to make sure he’d be okay to come into the studio the next day.

DC: Did you know what you were going to do when you moved back to Majorca?

MA: I had no idea. I had this little €200 camera so then photography happened. One day when I went down into the well, the damp and dark atmosphere felt right to me because it seemed as if we were all sleepwalking into chaos with the climate crisis. And then when I came off the drugs and alcohol, I invested energy into me. My first series was with the mannequins – I dressed three of them up in my collections and did their hair and make-up and put them in my car. I drove around the village, up into the mountains, the hills, inside a castle, into a monastery – people thought I was going crazy! It looked like I was sat next to Anna Wintour in the front seat of my car. From then I started to see myself more and things became lighter, I started working inside the well with this small window of light and I felt so happy – I felt that I could finally express myself without needing anyone else. I had no deadlines, I did it because it was a necessity for me. I have no show coming up, but I run around like I do all of the time.

DC: Do you have everything in your archive? Is it well organised?

MA: The archive is always moving because it’s not like an archive. It’s my wardrobe. I have everything! Some people stole a few things, but I have the Yankees baseball caps sweatshirts, the United Nations shawl, the Burberry raincoat. I reproduced some of them for my self-portraits too. If I know that I am doing a picture tomorrow, I need to prepare. I have a problem with shoes because I am size 47 and my shoes only go up to 41 so I need to customize them with elastic. Everyday my pictures are getting better and better and when I look at ones, I have done earlier I want to re-do them. I will never let anything go with my name on it if I am not totally pleased with it. My body, my soul and my suffering are inside everything I do. I am very tragic, very Spanish in that way.

DC: If you liked Miguel Adrover the designer, you will like Miguel Adrover today because now, what you’re doing seems even more pure.

MA: I have become good at knowing how I look inside the camera – you cannot jump into a picture with the clothes, there is a mediation before on who I am or what I am doing, or what I have inside me. It’s not just dressing up. I like to see my clothes in a new environment that isn’t a big city. A lot of them have been inspired by the Mediterranean, where I am from, so they make a lot of sense here but, at some point, the clothes are the least important thing. It’s about how you feel the clothes. A style comes after many years of being around, of understanding and getting into trouble with clothing.

Fall 2022

Couture Now

︎︎︎Published in i-D N° 369

Couture Now

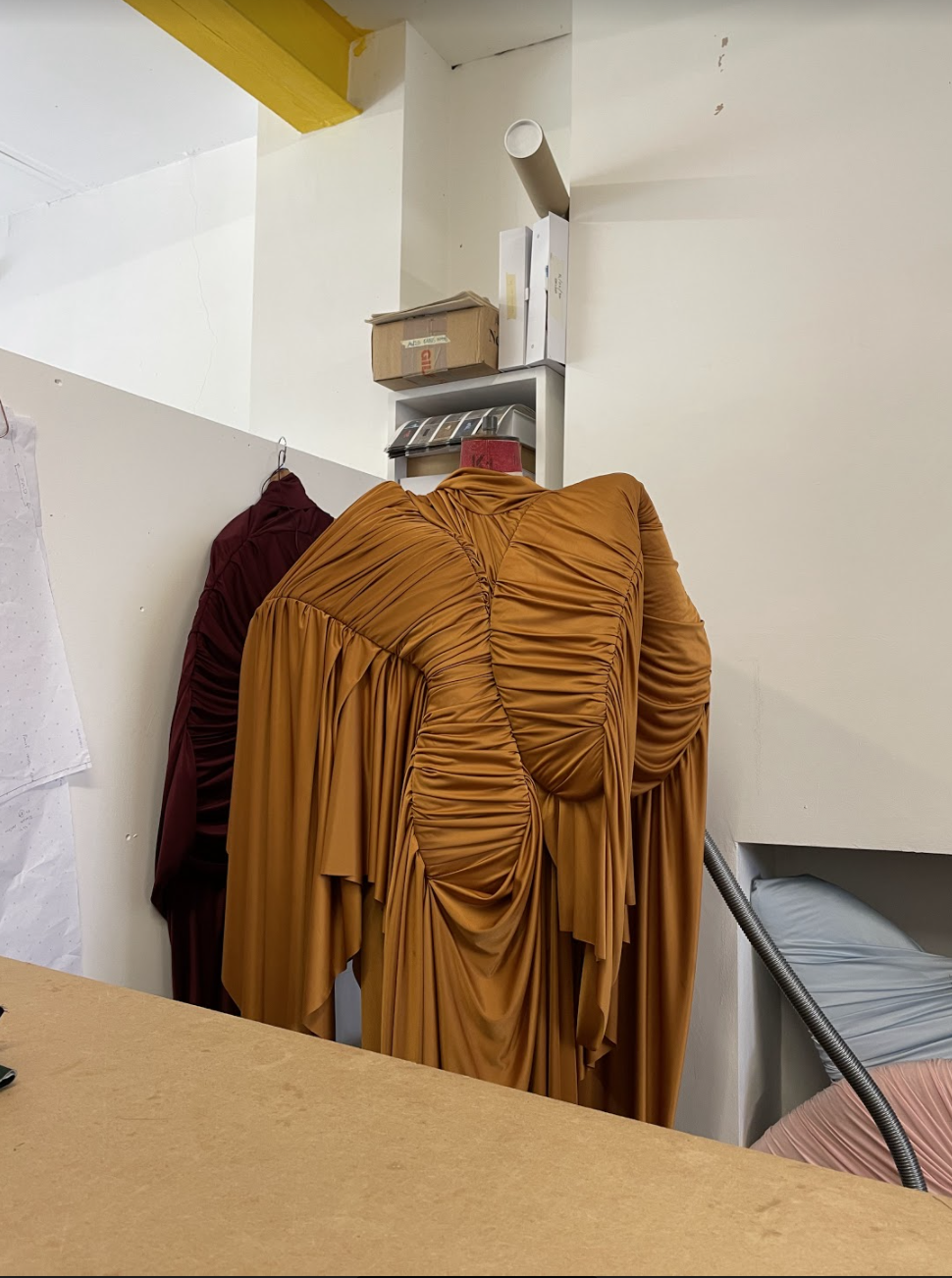

It was clear from the Autumn/Winter 22 couture shows that the designers couldn’t agree on anything. The costume gilt of Schiaparelli was trumped by the serenity of Dior. The elegance of Valentino was trumped by the camp of Oliver Rousteing’s outing at Jean Paul Gaultier. The formalism of Chanel was trumped by the strict sexiness of Alaïa. Yet the designers were unanimous that in couture the metier is all that matters.

Only houses approved by a dedicated commission run by the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture can call themselves true couturiers. Their clothes must be made in Paris – although, in recent years, Dolce Gabbana, Valentino and Fendi have encroached on the term, choosing to work and show in Italy as ‘correspondent members’. The rules are thus: houses must design made-to-order clothes for private clients with more than one fitting using an atelier that employs at least 15 full time staff. They must also have 20 full time technical workers in one of their workshops.

Couture is neither haughty nor superannuated. The overarching diktat is one of anti-mass production and pro artisanal craftsmanship built around the structure of a house and its staff, from the seamstress – les petite mains as they are known – to vendeuse (sales staff), from the model to delivery boy. At Valentino this year, the magicians from the workroom took their bow at the finale with Pierpaolo Piccioli, weeping in reverie at the audience’s applause. Peter Muiller at Maison Alaïa (which is not officially couture but tacked onto its schedule) even sent out white lab coats as invitations to his show in homage to the uniform of les petites mains.

The business of ready-to-wear fashion is a more industrial project, hurried by the rapid seasonal schedule; couture is where conversations between artists and artisans flourish. This is how Maria Grazia Chiuri has approached her tenure at Dior. “I like the tree of life symbolism because it is present in all couture,” she said after her show. “This idea of the circle of life is especially important in this moment, in the world, we all have to change the way we work, we have to think about how we can build knowledge in different ways, step by step. Couture is a more intimate project, a dialogue over a few months. You approach couture because you know what you’re buying.”

The iconography of couture – the idea of it, the look of it, even what we think it smells like – is engrained into our fashion thinking. It’s understood as a place where designers can function at the highest possible vantage point, making their own dreams come to life with fabric and cloth but only with the aid of les petite mains. Pierpaolo Piccioli rooted his collection for Valentino in the atelier too, explaining it as “the coordinates in which all our journeys converge, a tree with roots as deep as the underground of this city, where the seamstresses and tailors who understand my gestures, as they understood those of Mr Valentino, interweave the plot of each dress with their lives. In Haute Couture there are no paper patterns, no map, no trace except the one left at the bottom of the soul.”

The tired old cliches of expensive frocks for frozen faced socialites; or frou frou gowns worn once before being locked up in acid free paper echo differently in an age with a steadfast appetite for beauty. That a generation of fashion enthusiasts have been on social media since birth is vital to reframing what couture stands for today. The arrival of the iPhone in 2007 catapulted fashion – and the act of dressing and performing in one’s clothes – into a new, convivial kind of theatre. Today the fantasy of fashion has largely been drained out of it by a slew of testy marketing gimmicks and quickfire trends – it is harder for us to be surprised or awed by it. Couture then becomes all the more tempting to a heavy-hearted audience bouncing between TikTok and Bravo TV, revelling in its own spectacle.

“A lot of people started to ask me after the first couture, ‘how do we buy couture, who do we call?’ especially the younger generation we want to establish a dialogue with,” Demna said after his breathtaking Balenciaga show. The question of ‘how’ is an important one, and well-exemplified in Paul Gallico’s novel Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris published in 1958. Mrs Harris is a maid working in war ravaged London who sets her sights on buying a Dior gown. When a taxi drops her off on Avenue Montaigne she discovers “...not a proper store at all, with windows for display and wax figures with pearly smiles and pink cheeks. Arms outstretched in elegant attitudes to show off the clothes that were for sale. There was nothing. Nothing at all, but some windows shaded by ruffled grey curtains and a door with an iron grille behind the glass.” Once she manages to step inside, high off the odour of parfum, her shoes sinking into thick carpet, she asks in a thick cockney accent: “could you tell me which way to the dresses?” Mrs Harris is unabashed by the secret rules of Paris high fashion and rightfully claims her place within it.

Similarly, Demna has peeled the drapes from the windows at 10 Avenue George V – the historic address for the House of Balenciaga, opening a ground floor gallery suited to new demands of a metaverse-versed couture client. He said: “We thought we needed to create some kind of an entrance to the salon, a space where people would know about it.” Couture by measure of its bespoke service is not something that can be rushed, even if clients might want to wear it the same day to the next party. So this new space – this new attitude – does away with the haughtiness of the past. A lot of the pieces deal with volume and therefore don’t require a languorous made-to-measure approach. “The idea of couture is built into the technique, the material, how it is assembled, the innovation,” Demna said.

With its artistry, the world of couture is made for our mercurial digital age. An age where for most of us, the image is the experience. For A/W 22, Maison Margiela staged Cinema Inferno, a knotty Dantean labyrinth of multi-media: a theatrical performance, played out in front of live spectators, captured by cameras that integrated film simultaneously broadcast online. It was artisanal in attitude, curiously punk in execution. Galliano’s outings for Dior during the mid 90s to early 00s designed by Michael Howells are forever enshrined in fashion folklore as some of the most lavish ever staged. This magic and mania are what couture has always stood for and here, at a different house, in a different time, Galliano’s historicism and love of thirties glamour was infused with a digital kick.

Writing around couture often lauds the material over the mythic: the pleating of a skirt, the cutting of a jacket, the texture of a print. But we should note its overwhelming emotional impact, its euphoria. “You know, my mom always asked me: ‘don't you want to design clothes for Target or Walmart and make mass produced garments that would reach a wider audience?’” Daniel Roseberry said after his Schiaparelli show. “I told her that my life wasn't changed by going to Target. It was changed by looking at fashion shows and seeing beauty and being given permission to dream those dreams for myself growing up in Texas. The democracy here is the democracy of beauty and giving beauty to the world.”

Although couture is worn by the few who can afford it, it is revered by a global multitude gazing through the opulent portals of iPhone and laptop, where its values become surprisingly universal and transformative. “Every day the urge grows stronger to get a hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeliness, its reproduction,” Walter Benjamin wrote in 1936 reflecting on works of art in the age of mechanical imitation. In the opening up of couture – in its images, its videos, its objects – we are all invited into a monumental dizzying fantasy.

Instead of ideas about what to wear in the seasons ahead, couture gives us a chance to explore how we feel about artistry and artifice: a bouquet of flowers crafted from hand-painted and sequined silk, a jacket constructed from finely pleated hand-smocking; 70,000 crystals, 80,000 silver leaves, and 200,000 sequins embroidered onto 250ms of tulle. It is a contemplative respite from the fattiness of seasonal fashion. If ready-to-wear collections are Netflix shows, created quickly and in slick succession, endlessly streamed – then couture is the art house movie. It humbles and uplifts us with its otherworldliness.

Let’s not indulge the puritan panic of “who can afford this?!” We simply can’t afford to lose the best of what talent, time and material can achieve. Couture commands the body, the face, the mind and the mouth. Say “HAUTE COUTURE” out loud. Your lips will pucker, and your head tilt upwards. At once the term conjures up elegance and artistry. Drama and transcendence.

September 2022

Barry & Dylan

︎︎︎Published in Encens N°48

Barry & Dylan

He gets the beauty out of somebody

Part way through reading Nathan Jurgenson’s The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media recently, I began thinking about the value we place on pictures – and how this changes when we interrogate what a photograph actually is. Whether it is a physical object or a digital copy, a photograph remains ethereal.

The omnipresence of pictures has disrupted the human instinct to preserve and store. Jurgenson calls the type of digital pictures we are used to making on a daily basis ‘social photographs’ – they function more as language, used to charge an emotion, or exchange a point of view. This is a photography that will often only be looked at once before it is quickly passed over in favour of the next. He writes: ‘Photography, both permanent and ephemeral and everywhere in between, plays on the tension between the momentary and the forever, the transient and the fixed.’ This ephemerality responds to a ‘photographic abundance.’ The richness of our surroundings means that every single image requires its own classification. ‘In their scarcity, photographs can age like wine, with grace and importance. In their abundance, photos can sometimes curdle, spoil and rot.’ How does this help us to reconsider the photographic archive not as an ordered and neat space but instead as a site of immense hostility and complexity?

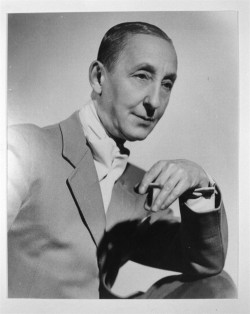

The legacy of one of the most iconic photographic talents to emerge in London in the mid-1960s – a time when the city became the epicentre for art, music and fashion – is today a few hundred plastic boxes, piles of papers, yellowed hand-written notecards, bright blue folders on Google drives, uppercase letters and digits collated onto Excel spreadsheets. Gigabytes, jpegs, tiffs. Memories and memoranda.

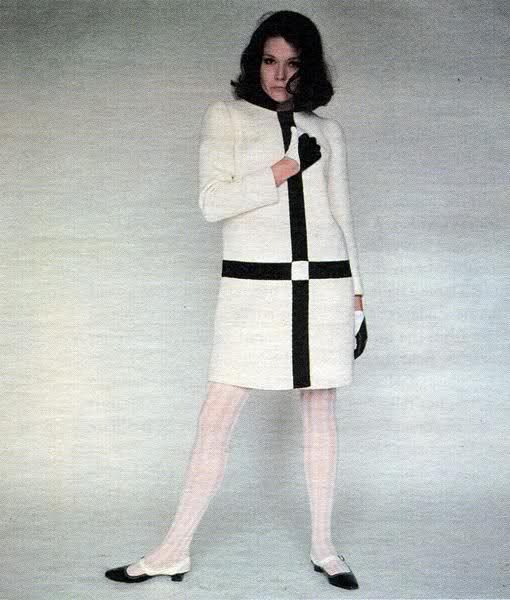

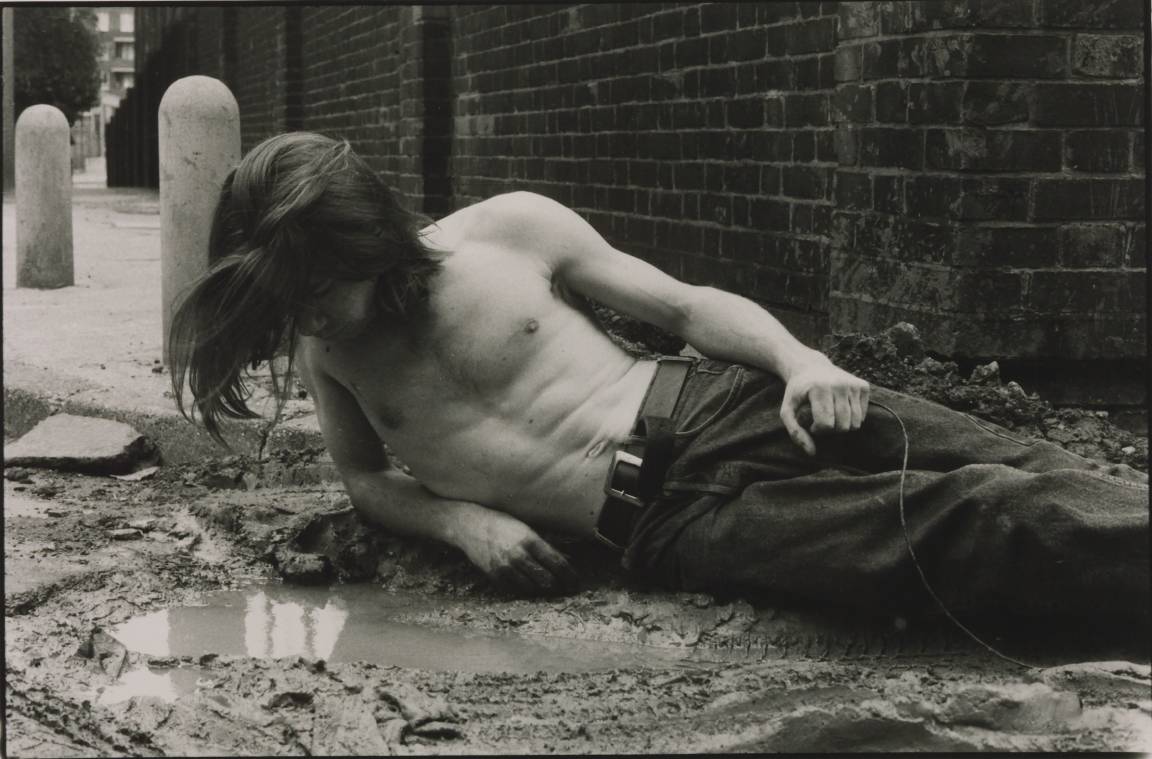

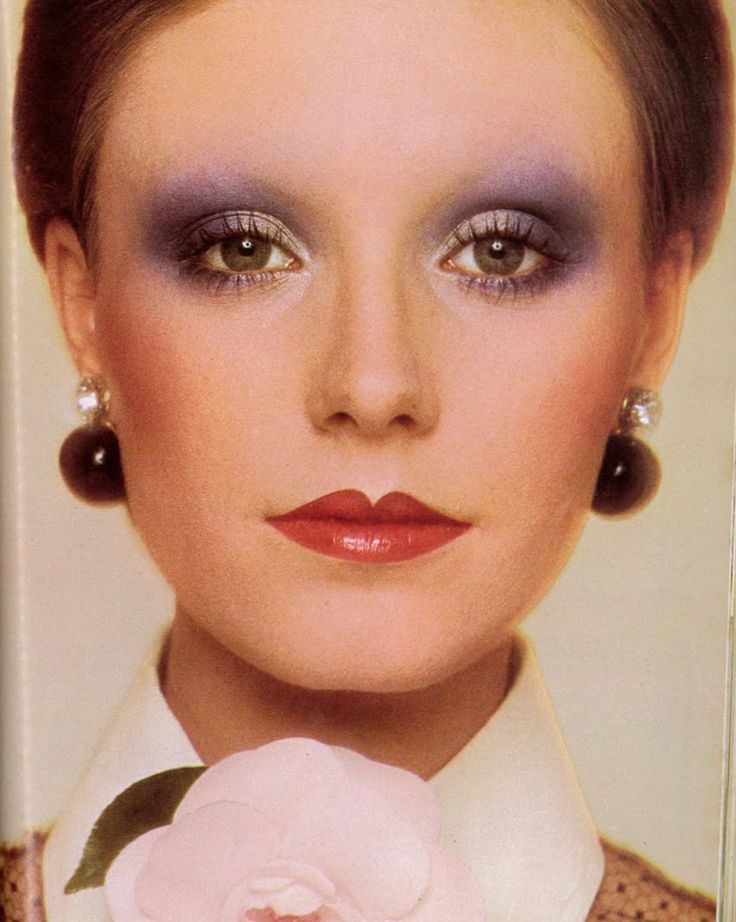

A black and white portrait of a wide-eyed teen wearing a Fair Isle jumper. Her hair trimmed short, she stares directly into the camera with eyes lined in hand-drawn lashes. She is unposed. Unabashed like a kite blown out to sea. She has just had her first ever photo session at Rossetti Studios in Chelsea with a softly spoken man called Barry Lategan. She is the ‘Face of 66’. Twiggy! In all her gawkish glory.

Lategan’s Twiggy pictures are burned in our brains – they are as much yours or mine as they are his or hers. Each of us, I think, shares ownership of the pictures we see. Yet in reality, the photographs from this seminal sitting are just negatives and prints inside an envelope inside a box to which someone has the key.

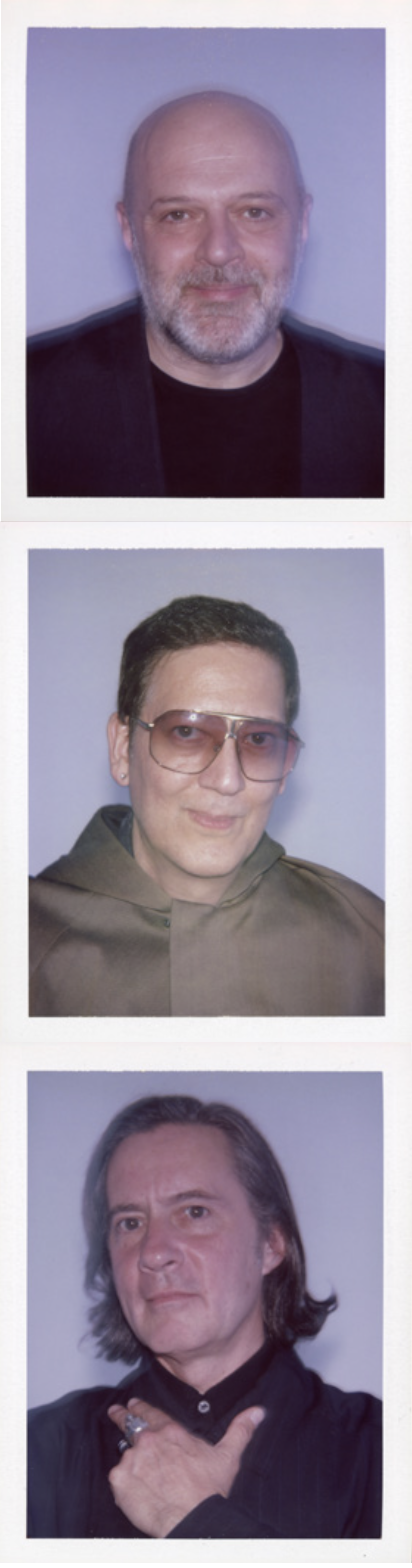

An archive is a mausoleum of memoir. A record of a lifetime’s work that still needs oxygen. Dylan Lategan is two things: a son who is anxiously managing his father’s estate and a man preserving the legacy of a legendary photographer who is unable to do it himself.

Over the course of his career, Barry Lategan established himself as one of the most renowned and influential photographers of his time. In addition to his fashion work, he photographed a range of notable figures including Paul and Linda McCartney, Calvin Klein, HRH Princess Anne, Margaret Thatcher, Salman Rushdie, Mick Jagger and many of his compatriot photographers, those guys who can be introduced with a single name: Bailey, Donovan, Duffy.

Following a traumatic brain injury in 2006 after falling down a set of concrete stairs, his mental health declined. After the loss of his London studio space in 2007, Lategan’s archive spent a number of years in storage. Dylan took photographs of piles of brown boxes, buckling under their own weight – lids crushed in, the metal arms of folders poking out. BARRY LATEGAN is written in black sharpie on the sides in various hands. Barry’s own loopy Y’s, sharp As and opulent Fs cascade down the side of one box with:

VIDAL SASSOON, nudes, Lily Cole, London Fashion Group, SALMAN Rushdie PLAYBOY, Joanna Lumley, Doris Lessing, Edward Hopper, ADAM ANT, Sarah Moon, Pirelli.