The Art of Joy

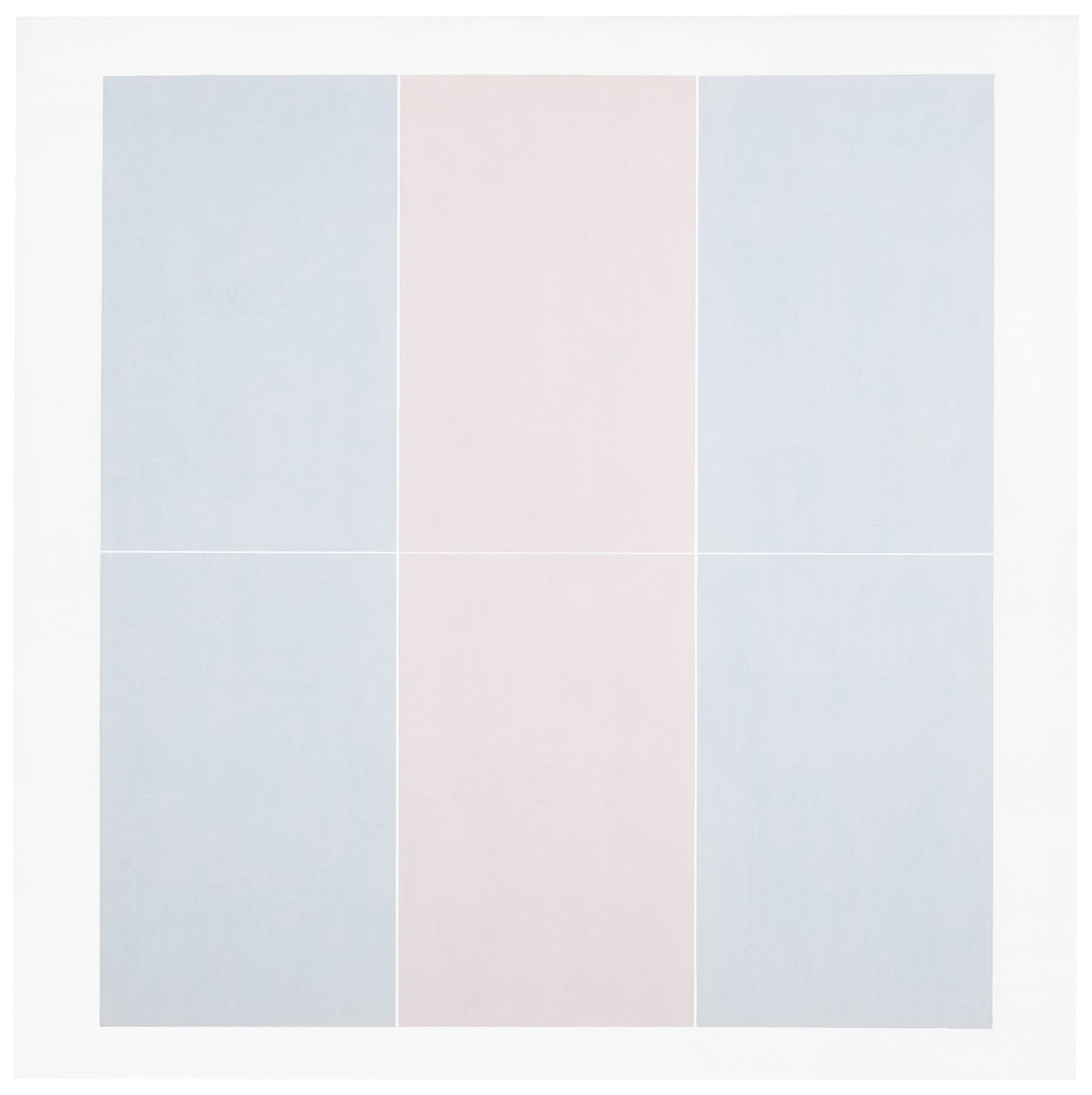

On this screen, pixels – tiny squares upon squares – align themselves to present an image of Agnes Martin’s art that is clear and crisp. At Tate Modern’s new retrospective her six-by-six foot canvases appear regal and sincere. In both settings, these grids of pale colour punctuate the chaos of our minds, daring us to see beyond the flux of daily life.

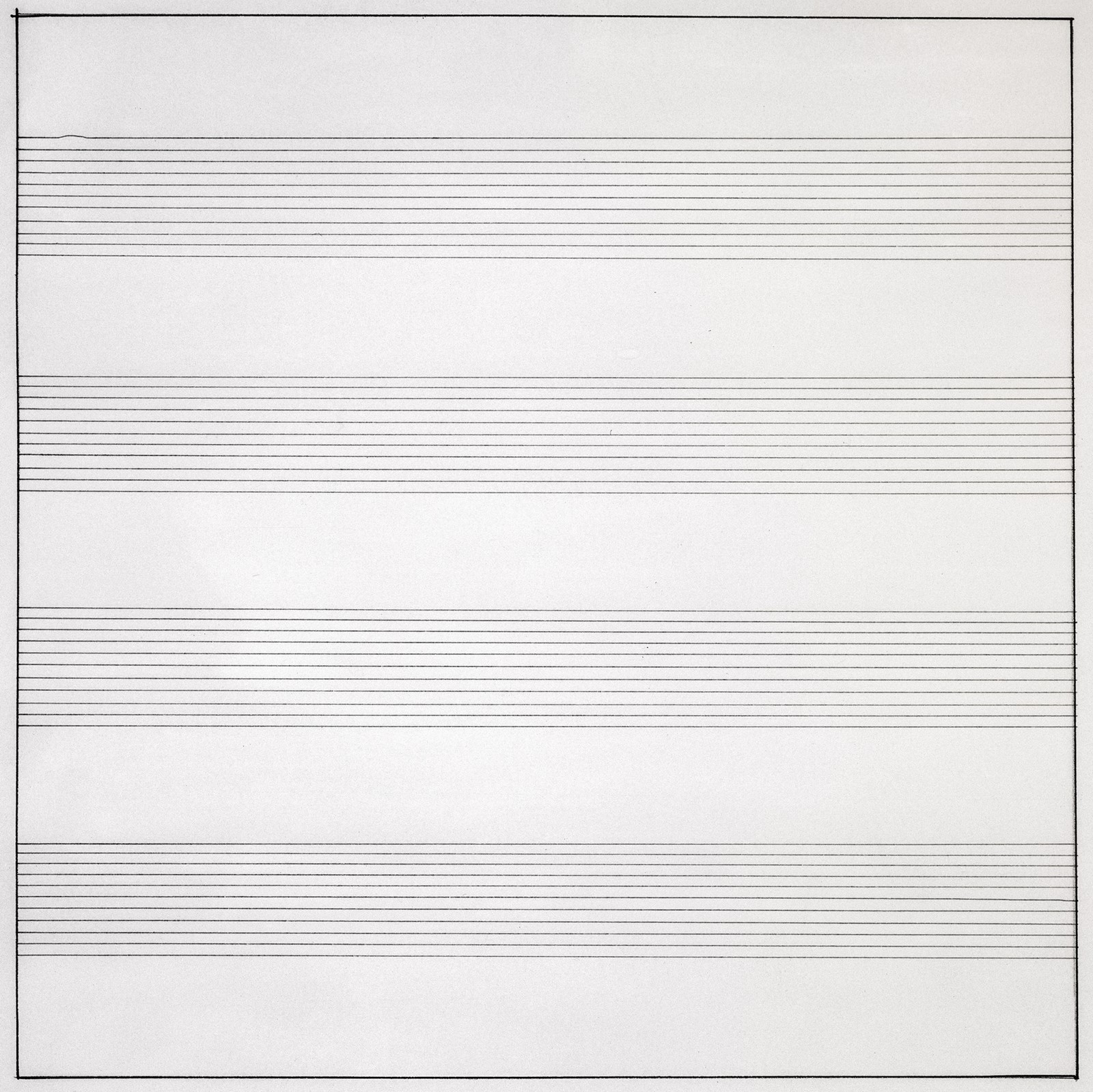

Martin’s studio practice was about waiting. ‘First, I have the experience of happiness and innocence. Then, if I can keep from being distracted, I will have an image to paint,’ she said. In a film from 1997, she talks about emptying herself of thoughts. ‘The best things in life happen to you when you’re alone; all of the revelations,’ she nods. ‘I have a vacant mind in order to do exactly what the inspiration calls for.’ Her eyes are puckish and wise.

!['Untitled #3' (1974), Agnes Martin]()

Agnes Bernice Martin was born on a rural Canadian farm in 1912. Growing up in Vancouver and the United States, she studied at Western Washington University College of Education, Bellingham, WA, prior to receiving her BA in fine arts from Teachers College, Columbia University in 1942. There, she attended lectures by the Zen Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki and became interested in Asian thought as a code of ethics. As the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer wrote, ‘her art has the quality of a religious utterance, almost a form of prayer.’

!['Untitled #1' (2003), Agnes Martin]()

!['Friendship' (1963), Agnes Martin]()

Following her graduation, Martin enrolled at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, where she also taught art courses, before returning to Columbia to earn her Masters in 1952. Martin settled in Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, where her friends and neighbours included the artists Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly and Jack Youngerman. Discovered by gallery owner Betty Parsons in 1957, she had her first one-woman exhibition a year later.

!['Happy Holiday' (1999), Agnes Martin]()

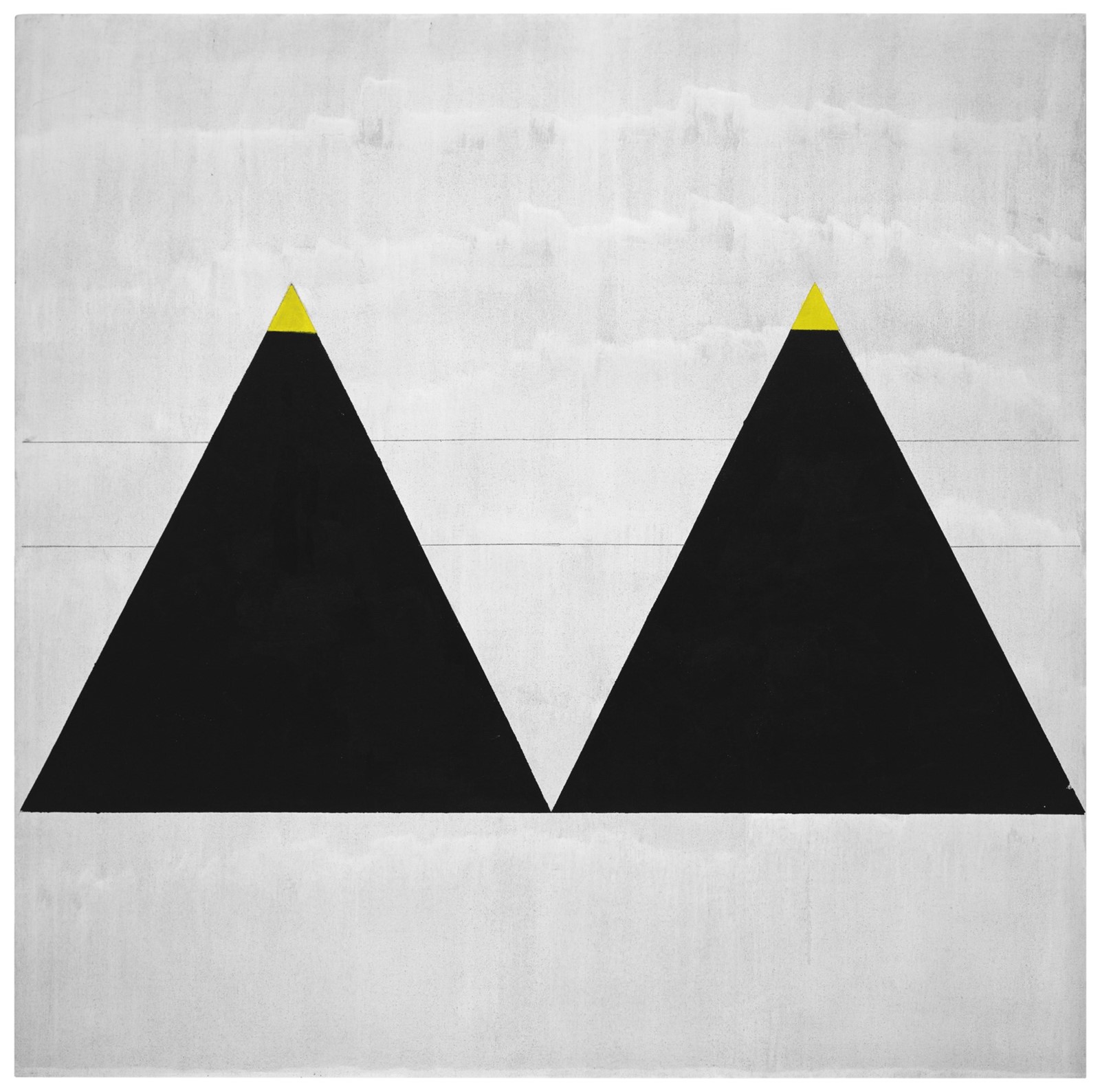

In 1967, her friend and mentor, the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt died. With her studio slated for demolition, she left the city for the desert wilderness in Cuba, New Mexico. She returned to art making in 1973, producing her seminal portfolio of 12” x 12” serigraphs on Japanese rag paper, reducing her vast surroundings to the purity of 30 hand drawn grid configurations. On a Clear Day established the grammar of linear division she would apply until her death in 2004.

!['Untitled #10' (1990), Agnes Martin]()

!['Untitled' (1977), Agnes Martin]()

!['Untitled' (1959), Agnes Martin]()

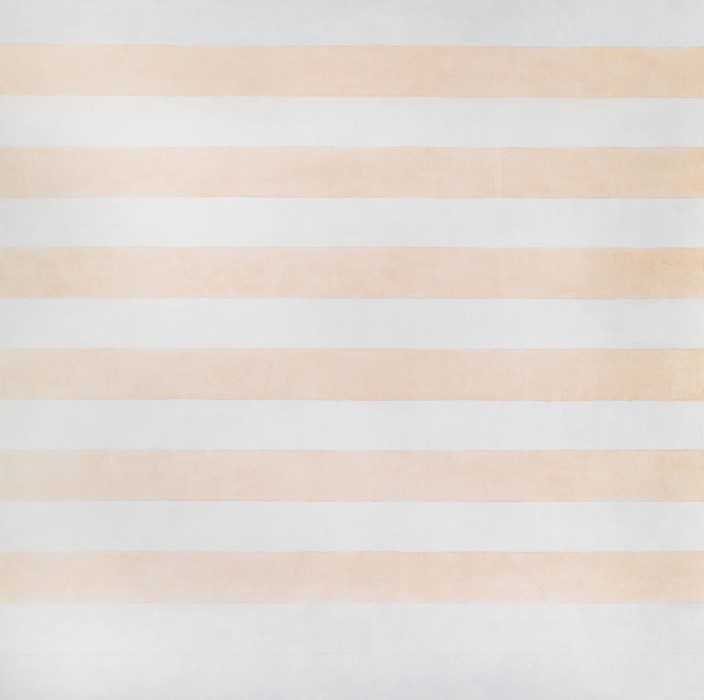

Her approach to both life and work was as austere as it was vivid. The fact that Martin had schizophrenia might explain her persistent focus on consciousness and perception. In The Tree (1964) she hoped to capture innocence; in the thirteen wide bands of alternate white and beige acrylic that make up Happy Holiday (1999) she communicates peace.

Martin’s language of geometry and monochromatic colour has been an important influence on many Minimalist painters – and, in fashion, S/S15 was her season. Designer Paula Gerbase for her label 1205 presented a series of elongated clothes inspired by Martin’s response to the desert landscape. For his second collection as Artistic Director at Hugo Boss, Jason Wu used a palette of pale greens, greys and white lifted from Martin’s canvases.

The film of Martin in 1997 shows a warm, peaceful and curious being. ‘We live a transcendent emotional life all of the time, all day long,’ she says. Earlier, she had stated: ‘absolute freedom is possible. We gradually give up things that disturb us and cover our mind. And with each relinquishment, we feel better.’ It is all too easy to dismiss the work of minimal abstractionists as clinical and unemotional, but look again. Martin’s paintings aren’t about squares or lines or grids. They are about our very existence – our struggle to find joy.

Agnes Martin

3 June - 11 October 2015

Tate Modern