2018

Nick Knight

Published in Modern Matter N°15

It’s About Seeing Death and Violence as a Transferral of Energy

Dal Chodha: I’m interested in your journey from documenting skin heads on the streets of 1980s London to photographing couture for British Vogue – which to me is the apex of commerciality, a sort of guidebook for fanatical consumption. They’re at different ends of a very, very long scale.

Nick Knight: I just see them as things that interest me. Life is so chok-a-block with things that are interesting, and I tend to get quite drawn to things I don’t know about. I’ve always been interested in sub-cultures, like the skinheads. I was a middle class white boy who didn’t need to be a part of that; I could have skipped it and gone to medical college, and never looked back.

!['Devon Aoki for Alexander McQueen' (1997), Nick Knight]()

DC: You’ve told me before that you became a skinhead to reject middle-class values. There was a huge sense of self-discovery too, wasn’t there?

NK: As a middle-class white boy in Seventies England, you were a bit of rebel without a cause because, you know, there wasn’t anything wrong. The whole of society was built to push and protect people like me, I wasn’t the underdog. Women were not represented. Ethnic minorities were not represented. Young middle-class white boys were where it was at. So I didn’t have anything to go against; but at the same time because of the arrogance of youth, I wanted to get involved in things to find out who I was. I think that happens to everybody. Skinhead was my way of finding out what and who I was.

DC: What part of the young man who did Skinhead is in you today?

NK: Quite a lot, actually. I’ve always had a sort of interest in violence – I think it’s an interesting force within society. In nearly everything around us – war films, or action films like Mission: Impossible, football hooligan culture, the military, boxing matches – the aggression is there. It’s a huge part of our culture and we tend not to acknowledge that. I’m interested in the energy and the beauty of violence, which I know is an odd thing to say.

!['Sleep, Natasha Prince' (2001), Nick Knight]()

DC: What do you mean by that?

NK: Like the end scene of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point – a modernist house is blown up and the pieces rain down like poetry. The physicality and that leitmotif has always been in my work, partly in the form of not seeing death and violence as a problem, but seeing it more as a transferal of energy. That is well represented in that scene: the contents of the fridge and the book case go up in flames and the books float down in slow motion, flapping gently, looking like birds. When I watched that film in the early eighties, it made me look at things in a different way. Images I am interested in are on one hand quite difficult but end up being beautiful. I’ve always wanted to do a photograph of two boxers fighting, like two thunder clouds coming together and in that way you can imagine it to be quite poetic, and romantic. Violence is in us in lots of different ways and I think the fact that we don’t really know how to talk about it is interesting.

DC: Did you see an aggression in fashion? Is that what interested you about it?

KN: A bit – my original entry into fashion was through youth culture, so there was the uniform, the code, the gang, that sort of thing. I saw the power of fashion. If you know the codes, if you’re wearing them well, you walk down the street with a certain arrogance. It’s always been there as part of my growing up, the idea of that cocksure, slightly aggressive street attitude that was prevalent in 70s Britain, which I don’t think is the same now. In terms of today, if you look at people like Gareth Pugh and Rick Owens, there’s a whole range of designers that play on coded violent messages. With McQueen, there was a lot of darkness. One of the things I’m working on at the moment is to do with people who have encountered extreme violence. I photographed a guy who was maimed in the Manchester bombing: his legs were blown up and his sister was killed. He wrote to me about a year ago and said he has his leg back together again and he was trying to emotionally get over the whole thing and it was would really make him feel that he had survived if I took his portrait. I got quite interested in this idea of people who encountered extreme violence but hadn’t signed up fit – who aren’t military people, or boxers, or whatever.

!['WAR' (1997), Nick Knight]()

DC: Would you say your fashion pictures are political in terms of how they’re made too? You’re working with such difficult subjects: how can a fashion image even begin to negotiate something like that?

KN: Are fashion pictures political? Yeah, I think so. They have a point of view. I’ve always quite emotionally attached to injustice, and that comes out a lot in my work – so depending on what I can do, I try and change things. Even within a big commercial cosmetics campaign, there are subtle things you can do. I tend to photograph people from below looking up because that’s a respectful position to have of somebody. Automatically that means that the women I photographed for Lancôme, for example, were being looked up at around the world, rather than being looked down on. It’s that little switch – a couple of inches of movement on the camera – that makes a big difference.

!['Iman, stills from More Beautiful Women' (2002), Nick Knight]()

!['Sleep, Zora Star' (2001), Nick Knight]()

DC: You once said that you liked fashion because it’s a hard thing to come to terms with.

KN: You can do a certain picture that everybody loves, and what it means is that you are in fashion; but then you’re also out of fashion. There isn’t a structure. If you are an actor, you do a small cult film, and then a mainstream film, and each time you’re building and building – like a young painter doing a show that flies in the face of contemporary art, and makes everything before it seem old fashioned and out of date. Fashion by its definition is built up and then taken down again. So if you’re fashionable, by the same token you’ll be unfashionable next season.

DC: So it is a bit like a game that you have to work out how to play. Have you felt that pressure?

KN: Yes, that has always been there. You always have to work out when to say what, when the right time is to do a particular type of imagery, or work with a particular designer. There’s an art to it. It isn’t a career structure based on you getting much support. Obviously photographers have managed to, but so many end up just playing the game. I think we suffer slightly from a problem with fashion imagery now: the dumbing down of the purpose of fashion, which is what I think a lot of mainstream fashion magazines did for a long time.

DC: They took out the complicated, challenging imagery.

KN: For a while, it presented women like they had nothing in their heads. Fashion has suffered; there has been a stupidification of it, a sort of ‘anybody can do it’ attitude, where the camera goes off and that’s it, you’ve got the picture – and that’s good because it looks fresh and new, but ultimately, it shows no investment in the craft of getting an idea across with imagery. Social media needs constant feeding too, so big brands who would invest money in ten images that would last six months, now do so for pictures that will last less than 5 days. They aren’t putting the same investment into it. Different times do have different ways of communicating, none of which I think are right or wrong. I think social media is a different system and we need to learn how to play it, we need to know what sort of images work in that way; but I think the abandoning of your craft isn’t good. I think the presentation of women who have nothing inside their heads isn’t good, and I think the idea that people under-invest and still think they have can have performing imagery that will stay in people’s minds isn’t good.

DC: Your campaigns with John Galliano for Dior from the early noughties are popping up online a lot at the moment. It might have something to do with the return of the saddle bag, but it made me think about the power of those pictures. You used to be given weeks to create that imagery, hours and hours of shooting and we’d only see a 10th of a second of it all. Do clients come to you with those photos and ask you to do them again? What do you say?

!['Devon, stills from More Beautiful Women' (2002), Nick Knight]()

KN: I have certain things I am trying to say when I take an image. If you think of photography as communication – that you are saying something, or at least that you feel you are – you wouldn’t want to go back and have the same conversation you were having ten years ago, would you? The excitement is in trying to do something new.

!['Dolls' (2000), Nick Knight]()

DC: But how do you avoid falling into that trap? You talked earlier about Skinheads, being out in the field, and being very physical with the work, being outside and open to the elements. Yet I think a lot of people recognise your work from the last decade as being firmly situated in the studio, a hallmark being the grey backdrop.

KN: The reason I started going to the studio was firstly because of logistics and secondly because I try to understand something. So when a Yohji Yamamoto coat comes out that looks like a mac at the front, a Crombie at the back and has a huge red bustle sticking out of it, I really didn’t need to see a tree, or a car or a bush or a café in the image with it, because this thing was so fascinating. When you look at that McQueen piece and it is a skirt made out of wood, and it’s like an angel’s wing: I just need that. The other day I was looking for something and I Nick Knight into Google image search and I thought, they’ve all got fucking grey backgrounds! They look like the same image, what’s going on!? For somebody like me who always wants to do something new all the time, I thought, my God, I actually haven’t.

DC: When you did that search did it make you want to start shooting differently now?

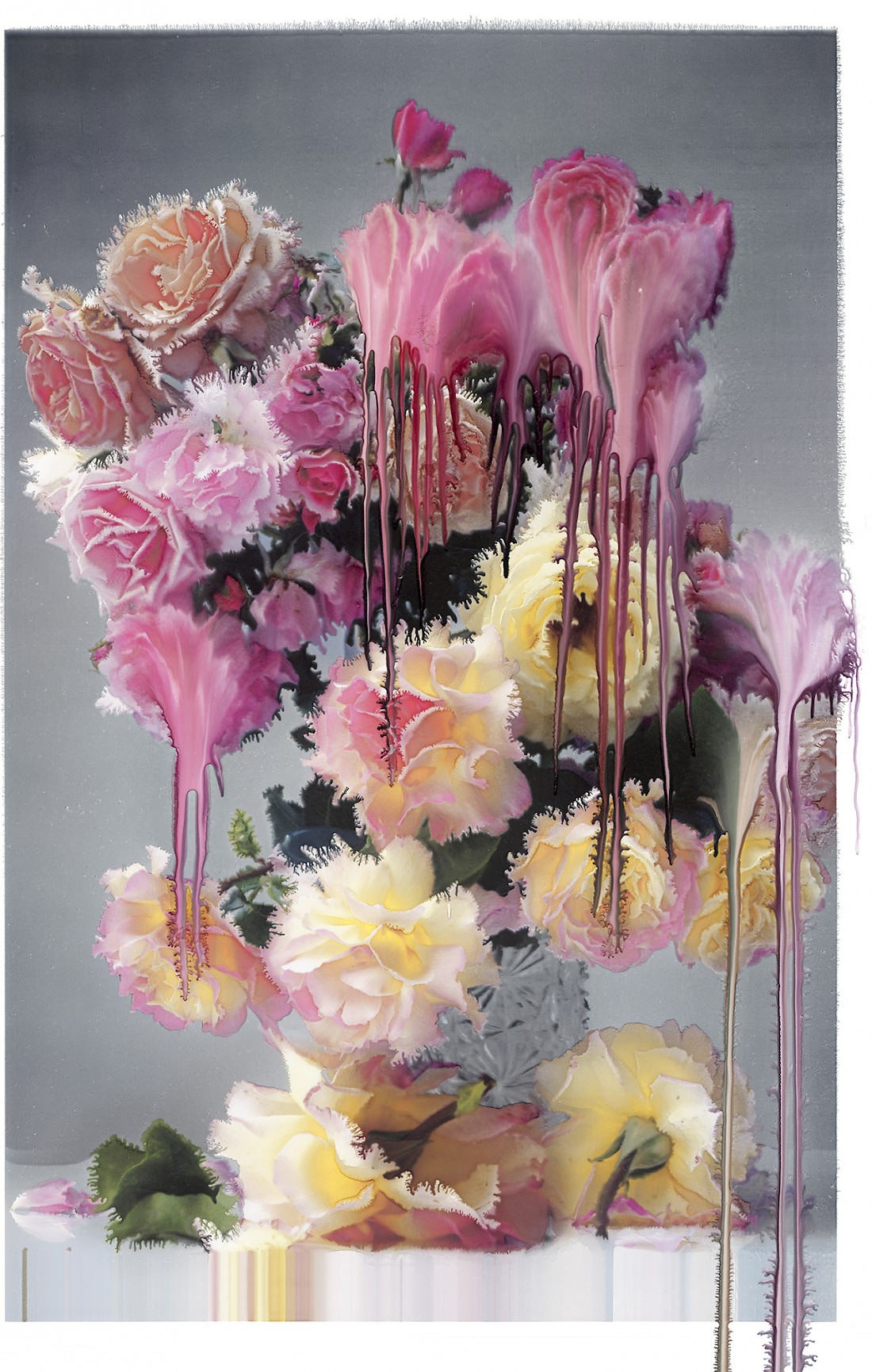

!['Rose 1' (2012), Nick Knight]()

KN: I just thought I was more varied than that – but I also know that people just go to the images they like the most and what I saw was based on an algorithm, so it tends to be that, I hope. I do a lot of obscure visual objects that people don’t pick up on too. For example, I wanted to re-enact Shakespeare and we recontextualised The Tempest and shot it in an army barracks some years ago. I like the idea of spontaneous performance, so often I will engineer circumstances that will happen so I’m photographing a performance and you don’t know what sort of imagery you’re going to get. But sometimes those images are less understandable so they come up less. There’s lots of stuff I do that doesn’t have a grey background.

DC: Would you say the photographs are quite serious?

KN: I’m not a big fan of humour.

DC: Yes, I didn’t see your work as being very playful.

KN: A lot of people have made that comment to me. I’m relatively playful as a human being, but I don’t like humour in fashion. I laugh very occasionally; I don’t like much comedy. I’m much more likely to cry in front of something than I am to laugh, although I don’t think I’m a miserable person. So yes, I do take it seriously. I think it’s also the idea that you are putting your heart and soul into something – there are so many issues that I feel very strongly about that are not funny, and those affect my psyche quite a lot. I get quite disturbed by Brexit or social injustice, by human suffering. I don’t find life to be a big bundle of laughs – but that doesn’t mean to say that I find life miserable. I’ve found a lot of pleasure in life.

DC: But is that something that’s innate, this hunger you have, this consistency for looking, exploring, improving? Do you think you either are like that or you aren’t?

KN: I think so. You know, I think we suffer from the idea that we are looking for a plateau of happiness, that that’s what life is about, it’s about putting things in order so we can be happy and I actually don’t think that’s a good thing to do. And I’ve said in the past – mainly to my children who can’t understand it – that I don’t think life should be about being happy, I don’t think that’s what we should aim to be, I don’t think that’s important, I think there are other things. We should feel absolutely connected to all of our emotions.

DC: There doesn’t seem to be much room for nuance. Everything you see or read is about reaching for happiness, which is only once facet of being alive. If we look back, a lot of the clothes you were photographing in the early noughties weren’t about making people feel comfortable, they had a real point to make about life.

KN: I think the generation coming through right now are very interesting because they have a different structure; we were all fighting to get our voice heard, but of course now you get your voice heard straight away. I never ever want to say it was better or worse in my day. They were different times but no better, no worse. We have the same human condition. We still fall in love. We still see things that are tragic. We have the same doubts, problems and desires.

DC: You’re very careful not to fall into the “oh, kids these days” trap.

KN: Yes, because I am aware that it’s a trap that gets you nowhere. Once you fall into it, it falls around you and you dismiss everything new. It’s a closed door. You know that TV programme about grumpy old men, all in their mid-50s complaining about stuff? It would be like that. Going back to our earlier conversation about finding my identity through becoming a skinhead, my children did that to me and I remember thinking, quite naively like any young parent, “oh I’ll be different, they’ll love me and I’ll be able to talk to them about anything!” Then, of course, they find the thing that challenges you…

DC: So do you still think that fashion is the right place to push a political narrative?

KN: Yes – but you have to choose your moment. Fashion is an interesting art form, in the sense that you have to know when you can say something in a strong way, when it’s appropriate to deliver that. If you try and put it into everything you do, it loses impact – it has got to be the right time. I’ve argued for ages that fashion has an absolute right – a necessity – to be political. People dismiss fashion far too easily, and part of the birth of SHOWstudio was for people to have a platform that recognised the power and importance of fashion without trivialising and scandalising it, which is how it was treated in the main media. People always say that this or that has already been done, and it really hasn’t.