September 2022

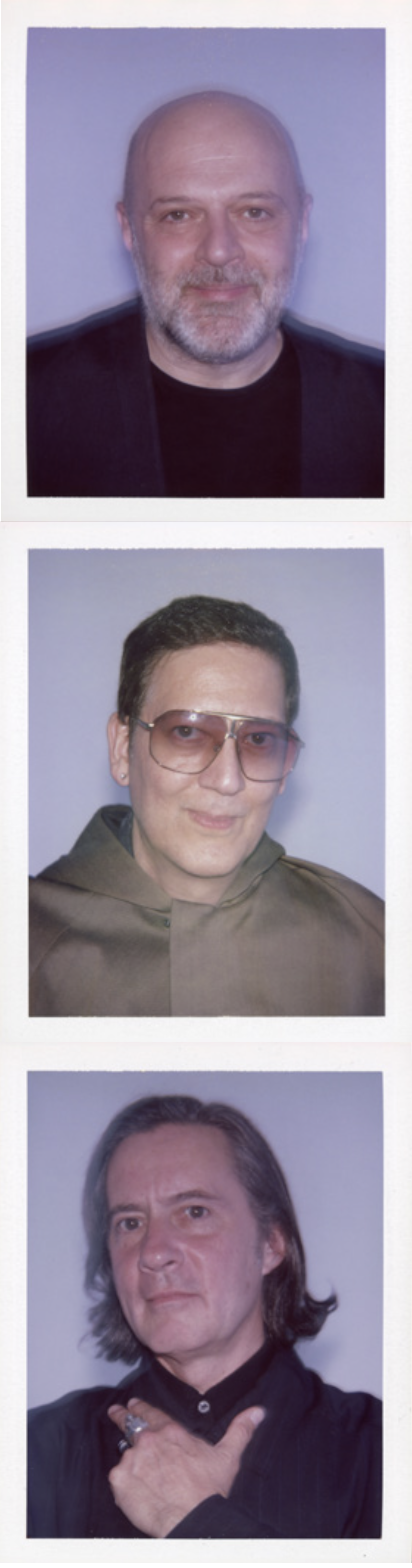

Barry & Dylan

︎︎︎Published in Encens N°48

Barry & Dylan

He gets the beauty out of somebody

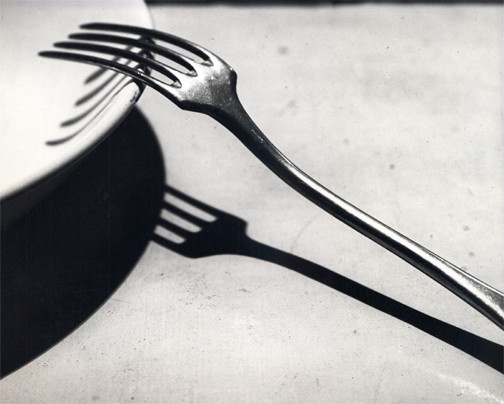

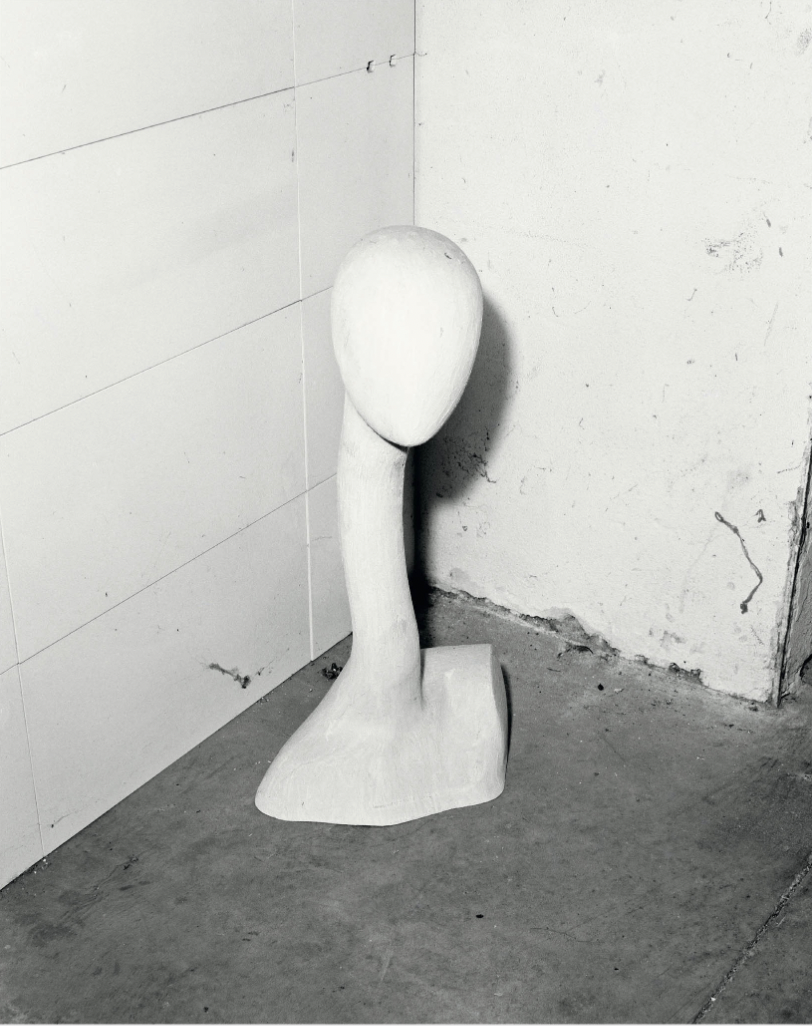

Part way through reading Nathan Jurgenson’s The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media recently, I began thinking about the value we place on pictures – and how this changes when we interrogate what a photograph actually is. Whether it is a physical object or a digital copy, a photograph remains ethereal.

The omnipresence of pictures has disrupted the human instinct to preserve and store. Jurgenson calls the type of digital pictures we are used to making on a daily basis ‘social photographs’ – they function more as language, used to charge an emotion, or exchange a point of view. This is a photography that will often only be looked at once before it is quickly passed over in favour of the next. He writes: ‘Photography, both permanent and ephemeral and everywhere in between, plays on the tension between the momentary and the forever, the transient and the fixed.’ This ephemerality responds to a ‘photographic abundance.’ The richness of our surroundings means that every single image requires its own classification. ‘In their scarcity, photographs can age like wine, with grace and importance. In their abundance, photos can sometimes curdle, spoil and rot.’ How does this help us to reconsider the photographic archive not as an ordered and neat space but instead as a site of immense hostility and complexity?

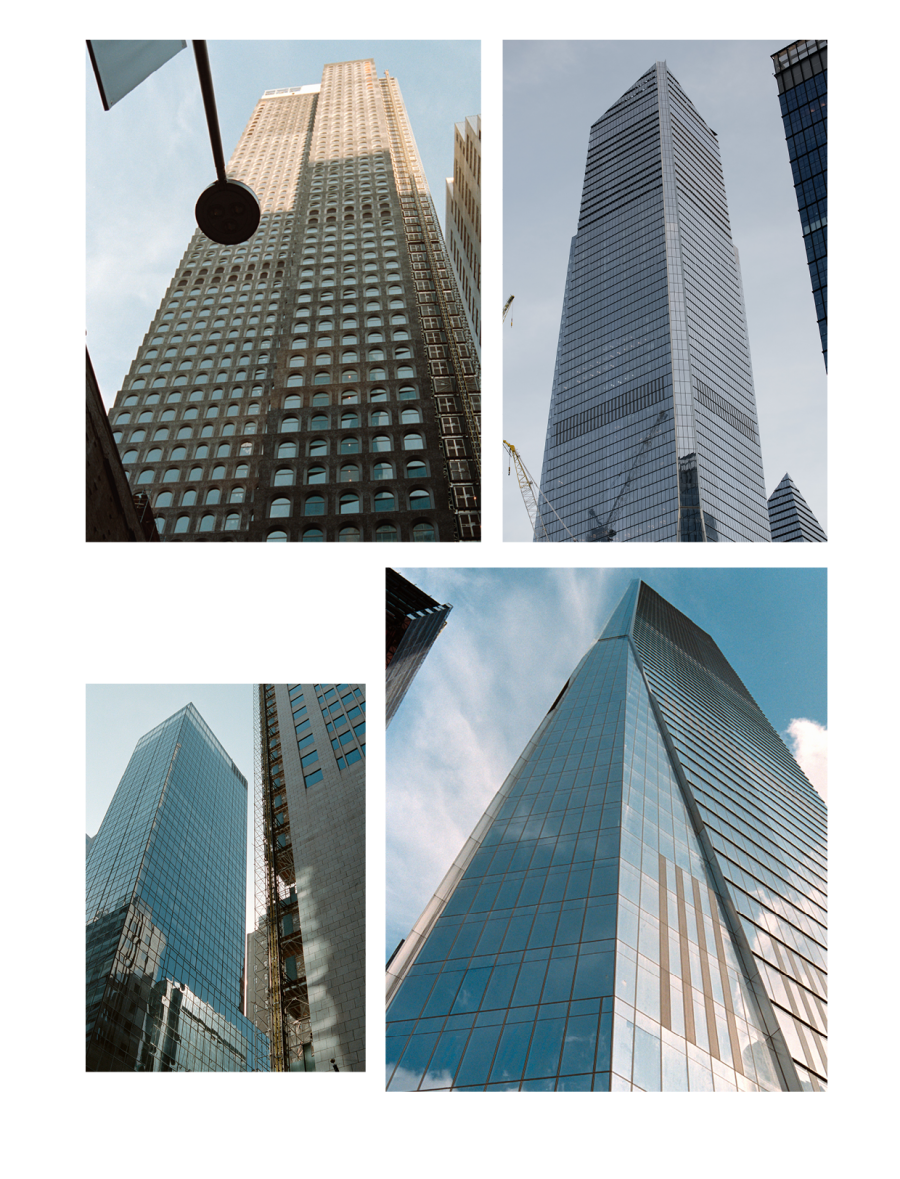

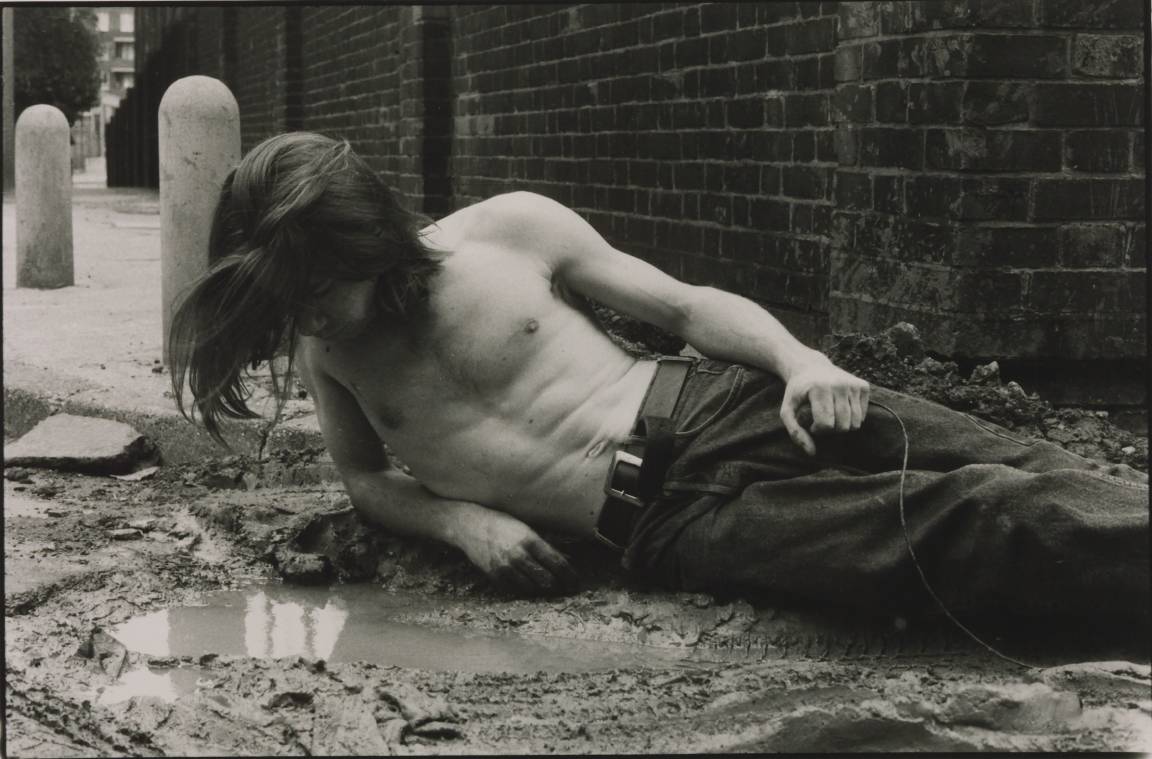

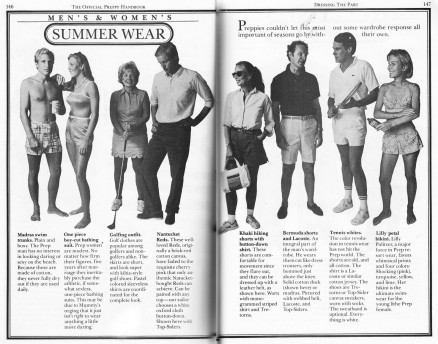

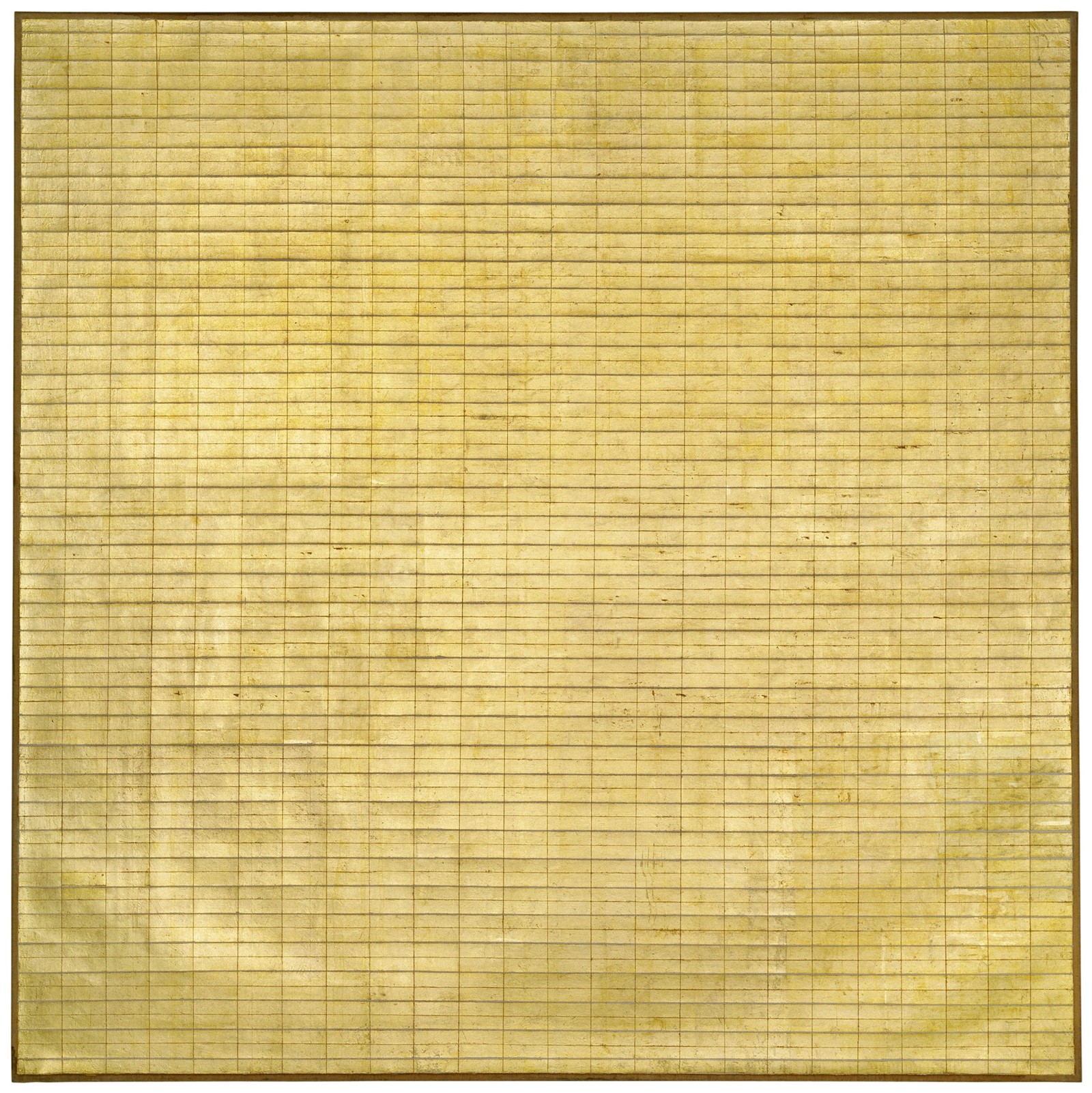

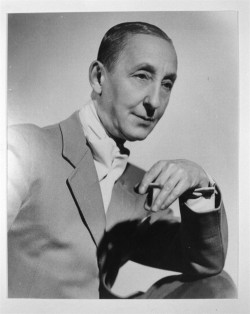

The legacy of one of the most iconic photographic talents to emerge in London in the mid-1960s – a time when the city became the epicentre for art, music and fashion – is today a few hundred plastic boxes, piles of papers, yellowed hand-written notecards, bright blue folders on Google drives, uppercase letters and digits collated onto Excel spreadsheets. Gigabytes, jpegs, tiffs. Memories and memoranda.

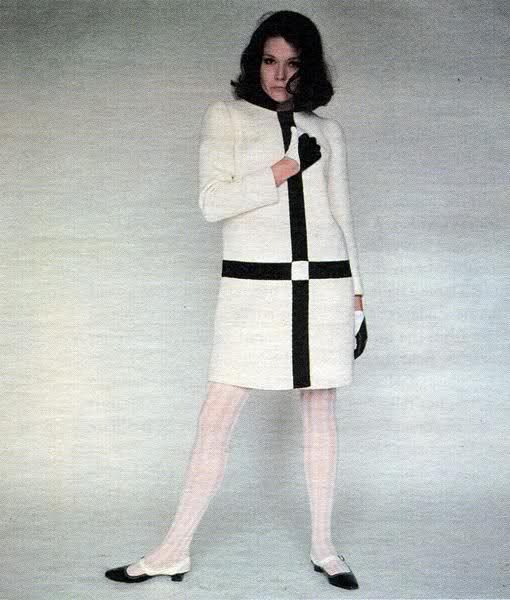

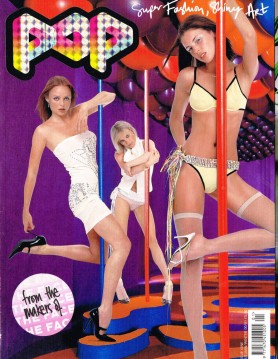

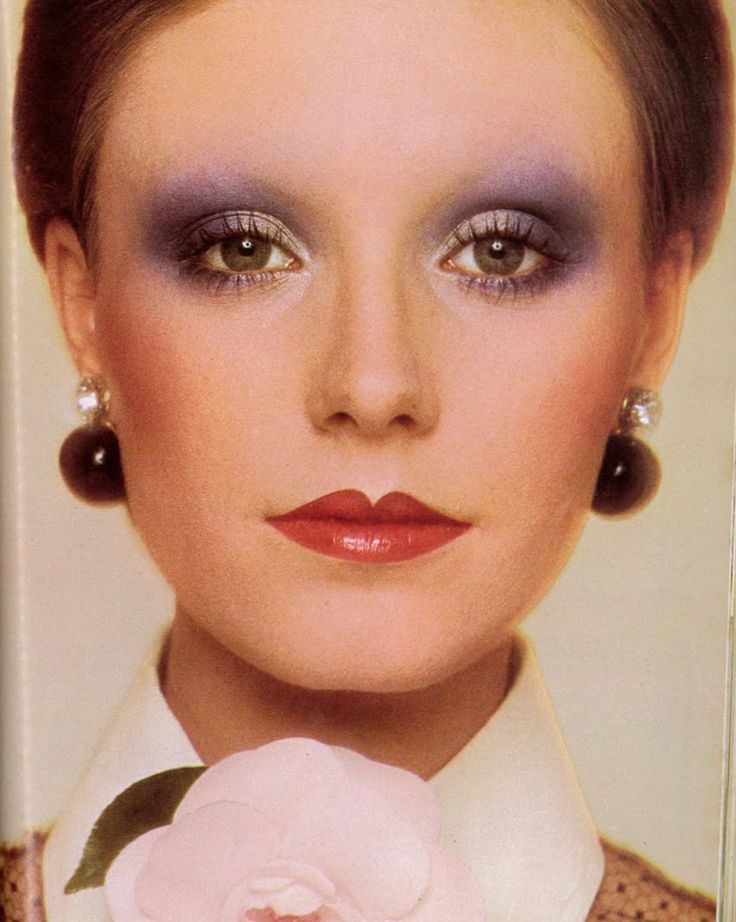

A black and white portrait of a wide-eyed teen wearing a Fair Isle jumper. Her hair trimmed short, she stares directly into the camera with eyes lined in hand-drawn lashes. She is unposed. Unabashed like a kite blown out to sea. She has just had her first ever photo session at Rossetti Studios in Chelsea with a softly spoken man called Barry Lategan. She is the ‘Face of 66’. Twiggy! In all her gawkish glory.

Lategan’s Twiggy pictures are burned in our brains – they are as much yours or mine as they are his or hers. Each of us, I think, shares ownership of the pictures we see. Yet in reality, the photographs from this seminal sitting are just negatives and prints inside an envelope inside a box to which someone has the key.

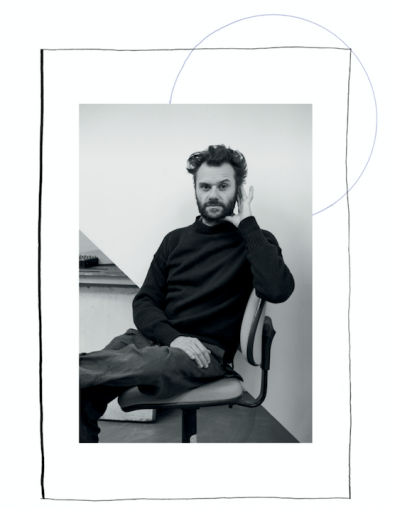

An archive is a mausoleum of memoir. A record of a lifetime’s work that still needs oxygen. Dylan Lategan is two things: a son who is anxiously managing his father’s estate and a man preserving the legacy of a legendary photographer who is unable to do it himself.

Over the course of his career, Barry Lategan established himself as one of the most renowned and influential photographers of his time. In addition to his fashion work, he photographed a range of notable figures including Paul and Linda McCartney, Calvin Klein, HRH Princess Anne, Margaret Thatcher, Salman Rushdie, Mick Jagger and many of his compatriot photographers, those guys who can be introduced with a single name: Bailey, Donovan, Duffy.

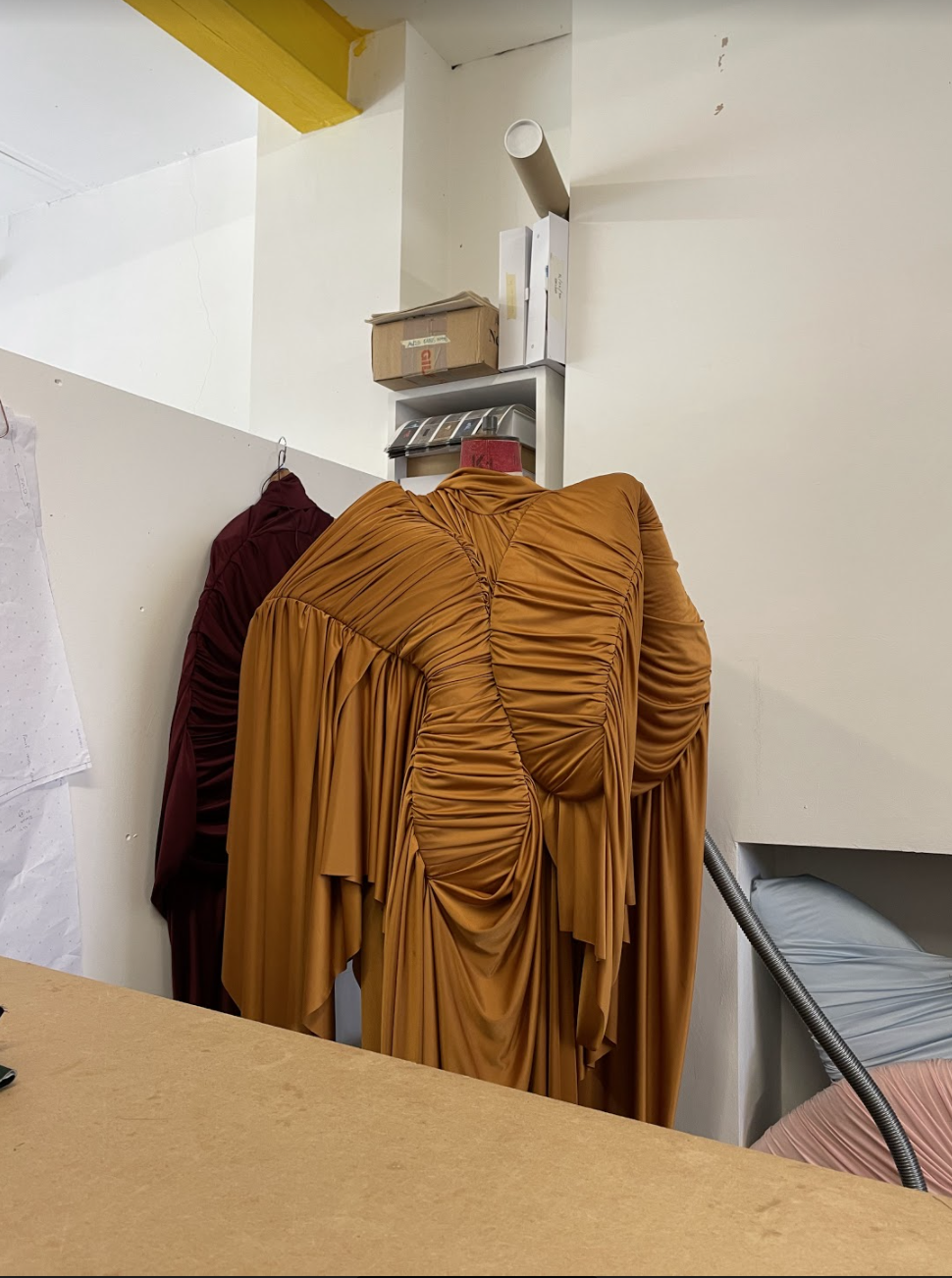

Following a traumatic brain injury in 2006 after falling down a set of concrete stairs, his mental health declined. After the loss of his London studio space in 2007, Lategan’s archive spent a number of years in storage. Dylan took photographs of piles of brown boxes, buckling under their own weight – lids crushed in, the metal arms of folders poking out. BARRY LATEGAN is written in black sharpie on the sides in various hands. Barry’s own loopy Y’s, sharp As and opulent Fs cascade down the side of one box with:

VIDAL SASSOON, nudes, Lily Cole, London Fashion Group, SALMAN Rushdie PLAYBOY, Joanna Lumley, Doris Lessing, Edward Hopper, ADAM ANT, Sarah Moon, Pirelli.