On page after page of John Bates: Fashion Designer (2008), one is struck by the breadth of ideas and multiple identities locked into the designer’s clothes.

Bates began his line in 1959 after he was flagged down crossing the Edgware Road by investors looking for the next big thing. London was full of post-war impertinence and Bates was poised to give it the shortest skirts, the newest silhouettes. Having begun his career in the mid-1950s under Gérard Pipart at Herbert Sidon of Sloane Street, Bates had by 1969 helmed 5 different labels that sold in 44 countries, creating a vast empire with his partner in work and life, John Siggins. His work spanned the flirty mini dresses donned in discos across the nation and the glittering costumes of television and film stars including Diana Rigg, Elaine Stritch and Siân Phillips. Bates dominated the British fashion scene alongside Jean Muir, Bill Gibb, Ossie Clark and Zandra Rhodes before closing the business in 1980 and later leaving London for the rural thrum of Wales. Today, both Johns live in an old farmhouse overlooking Carmarthen Bay together with a 5-year-old white rescue dog and a 21-year-old black cat. Over a three-hour lunch, they recalled the period with all of its grit and promise.

If John was ever missing from the office, you’d find him in some shop somewhere asking “oh, what does that do?” He’d go rummaging around these really dirty looking places in Soho that were filled with stock from before the war and find the most wonderful silk flowers that had been untouched for years.

John Bates: I’d use them on something and then the production in the business would say: “where'd you get the flower from? We can’t find them!” and they’d be so annoyed, but whoever had made them, did it so beautifully. I don't care if somebody says: “oh, that's old fashioned” – who cares? If you're going to use it, do it in a different way. There was a little shop next to us when we were on Berwick Street that had plastic which they were selling for tabletops and I thought, I wonder if I can use that for something. So, I bought a few yards, but we found that when you machined it together, it just opened like a stamp! It took a while to sort that out.

We tend to see all of those plastics and manmade materials that were being used in the 1960s and 1970s as a nod to the Space Age or something more futuristic. Was that something you were thinking about?

Not really, I just love plastic! And I did it with pure wool, which was expensive. The plastic was dirt cheap. People said it was silly, but it got publicity because it was very new in the late 1950s. We did two versions, both skirts actually and the papers photographed it so then we had to get it to work in real life! I'm sure there are machines you can use these days, but when you first start something, you've got to go through the problem pages. It was nice to do it first because everybody ohhh and ahhhed about it.

John would use anything if he could. I mean, the knockoff merchants used to copy us very quickly, but we did one dress with a shirt underneath and they couldn't undercut us because the fabric was so cheap. They were furious.

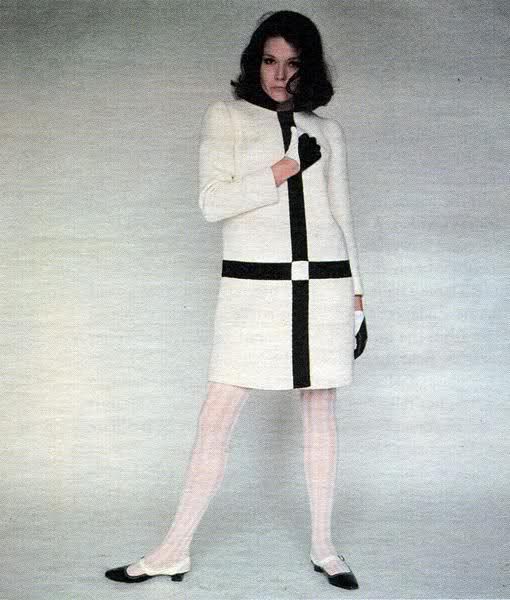

You had a couple of different labels – one called Jean Varon, which sold widely and then Capricorn, which was your coats and suits line.

JB: Yes, and they were very expensive. People looked at them and said, “hmmm very nice. Next!” But we kept on doing the softest leathers you could think of, they felt like silk, and beautiful furs, but the price when they were finished was astronomical.

JS: We had one customer from Leicester who came down every season to buy. She cost us more in smoked salmon sandwiches. That’s how many dresses she bought. She’d always buy 12 frocks and no more. People come in and begin to know what you do better than you do – they look around the rails and if anything hasn't changed then they get bored. I always used to say: “change everything around! Make it look different!”

DC: You had shop in shops too, where you could offer your own vision of the collections rather than an edit bought by someone else.

And that supported the whole collection. I remember when I was working at Hebert Sidon, he loved French clothes, but every season in the showroom you’d hear: “Oh, it's very nice but hmmm I don't like the colour. I really don't like this…” Everything was going downhill. Have you ever seen people's faces when they are buying a collection?

DC: Oh, during the sales period? Yes. It’s quite brutal.

They all go: “Yes, it's lovely. But it's not for me.” I was never allowed in the showroom because I would say to people: “Well, you have to have the clientele. If you don't then it's not the right thing to buy” and the sales staff would throw me out! When the Paris things used to come out, all the shops read the magazines and the papers.

DC: What was it like for you working with the press? You had some important long-standing relationships with many editors.

A fashion editor on a paper will have a different attitude towards fashion and what's right to wear. Vogue and Harpers have another idea based on what photographs well. I mean, I didn’t know much about business when I started out or that you’d have to go around to parties talking to people, which I’ve never been very good at. When I first met John, if we ever went out together, he’d sail into a room and talk to everyone. I’d look for the nearest corner and stay there.

DC: How did you both meet?

JB: I was invited for dinner at a mutual friend’s place. It was around 1965. This friend, Dennis, had a piano covered in lots of silver framed pictures and right at the front there was a wonderful photograph of this man. I sort of stopped and said: “Who's that! I’d like to meet him,” which is a pretty bold thing to say, and it was John. It's funny how lucky you are with things. It was very unusual for me to do that, to be so pushy about meeting John.

JS: I was at my flat in Maida Vale painting the walls and there was a knock at the door. It was Dennis and he said: “Hello. We've come for a drink” but by the time he’d got that out, John had run back down into the lift.

JB: And that was the opener! A day later John got a telephone call from me saying: “If I buy a cake, can I come for tea?” I mean, talk about corny.

JS: We started working together a year later, around 1966. John had a PR guy who worked for an agency, and he’d decided that he was going to Hollywood to become a script writer. I was doing ad hoc days for someone who had a PR agency, oh, what was his name?

Lampuki!

JS: No, Lampuki was a PR agency on the Kings Road. I did one day a week there. One of the founders was Geoffrey Aquilina Ross, that’s it, he worked for Vogue doing menswear. That was absolutely mad. The office was full of real Chelsea Girls, swishing about town. They’d come in at 11am because they were so tired – they all worked at Mary Quant’s restaurant in the evening or waited tables at Alexander's. Then they’d go out to parties, so you never knew where they were going. It was a madhouse. One day they all went off on holiday and left me in the office. We had a huge Guerlain job on. They were launching a campaign for skincare for women over 40 and the first ad was going to be in Nova. I got the proofs and went along to show the client and he signed it off but when the campaign was printed, she was bright red – it killed the whole thing! Talk about panic stations, the phone was going off the hook. After that disaster I started to work for the guy who did John’s PR.

JB: He did a few people, but he wasn't pushy. He knew girls that were working as assistants at the magazines. He was a charmer. He knew Penelope Vincenzi and she’d just got that job at the Daily Mirror, so he introduced her to us. You couldn’t get anything good in newspapers at the time.

DC: What was that PR game like, because from reading the book it feels like you had so many champions? Prudence Glynn and Ernestine Carter were real fans of what you were doing. And Marit Allen.

The trade read The Sunday Times so that made a big difference. If Ernestine put you in the paper, the shops would come in immediately and other manufacturers would take note. When I took over the PR, the first thing I did was to develop the provincial press because they were starved of stuff – they couldn’t afford come to London.

DC: How did you show the collections?

JS: There were no coordinated shows. We had the showroom and would show three times a day to buyers each season. Press got in when they could, I mean, I basically went to lunch with them, or John did and showed them the collection afterwards. Ernestine was great.

JB: She was. A lot of people said all sorts of things about her.

JS: She did like a drink, but she was very proper. After a big business lunch, you’d take her back to the showroom and you’d always have to angle the rail at 45 degrees because she couldn't actually walk in a straight line. She’d always pick something – it didn’t affect her eye.

DC: How did you feel about that? People critiquing or editing your clothes?

JB: There aren’t many people who can look at a rail full of clothes and know exactly how the designer wants them to be shown. It's very difficult. But some of them know immediately. Ernestine was wonderful. And Prue [Glynn]. And Marit Allen who I met when she was at Queen and just about to go off to Vogue. She came in and looked at 12 things on the rail and said: “Oh, I could do all of these” – she was with Caterine Milinaire. The frocks were short and when I saw the pictures in Queen, she’d put them on Grace Coddington and another girl. Grace was sitting with her leg up over the other and I thought, “oh my god, nobody’s going to come in and ask for a bum freezer skirt!”

JS: Beatrix Miller left Queen and went to edit British Vogue and took Marit with her in the end.

Marit got hold of the Queen guy, the publisher Jocelyn Stevens, when he was in the lift and she said to him: “I could do your pages you know! I read them all the time and I can do it better!” She must have put on a pretty good show because she suddenly got the job! I must say she pulled out all the stops. People thought that Queen was about the horsey set, but you know at the back of the magazine were two fashion pages and that was where the two fashion girls shone. As an editor of something like that you have to be careful of what you do, because everybody’s looking.

And they all wanted exclusivity. I mean, the big mistake people make about Vogue is that it’s fashion. They're in the publishing industry. They're not in the fashion industry. They're selling magazines so advertising is important for the editorial content. It’s all business. If we were starting up business now, I don’t think we’d even bother with the press. These days, you've only got to look at the papers, the weekend magazines don't photograph fashion anymore. It’s got nothing to do with fashion photography.

DC: Were you friends with other designers?

JB: We knew people like Mary Quant and Zandra Rhodes, but we weren’t friends because what they made didn’t really appeal to me and we rarely saw them socially.

JS: Plus, we were working. I mean, people think, you know, the “Swinging Sixties” but it was bloody hard work! We'd be working all day and instead of going home at 7pm we’d go down to San Lorenzo and have supper because that was the easiest thing to do. And we’d carry on talking business. It sounds grand but it wasn’t really. We'd sit there talking, have another bottle of wine and then the table would grow and during the course of evening we’d finish up with about eight people around the table. It was great, great fun, but we’d all come from work.

DC: There’s this misconception that the Sixties was just one big, massive party.

JB: It was hard work! Some of the times were fun, I mean, Granny Takes a Trip. I say that because I don't know anything about it, but those types of shops with all the murals on the wall, you’d go up Carnaby Street or the Kings Road and they're all there, vying with the other. Some of the things were made in very peculiar things like very cheap satin. Now, it's one thing to use cheap satin. It's quite another to make it work for you.

JS: …but it didn’t matter because it was cheap! And if you wore it, it was fun. I remember wearing a check pair of hipster flares back to Aldershot, which is a military town. I got off the train and walked through the station and I saw three army trucks pull up and boy did they give me a hard time! Talk about wolf whistles.

JB: You had to be brave. You still do. I did a lot of bare midriffs, short things and low-cut necklines and some of the girls would ask to borrow clothes to wear to parties. But you know, once you got into a party with guys, they’d always say to the girl “have a seat” and the men always flopped down onto the floor. It took me a while to work out why – it was so they could look up their skirts, so I used to say to the girls: “stay off the seats and stand around!” Most of those girls who wore designer things were brave.

DC: A lot of the clothes you made were quite revealing. You needed to have confidence. I like what you said to Model Girl in February 1967: “A dress is a prop, no more. It’s the way that she wears it that counts.”

JB: Well if you don't wear something looking happy in it then it won’t succeed. You’ve got to put something on, know it's absolutely what you want for the place you are going, and sail into the room. You can have such beautiful dresses sometimes and the wrong people wear them. People don’t know how to look alluring anymore.

DC: What do you think about this notion of “The London Look” and how much do you think Jean Varon was a part of it?

JS: I remember walking down Great Marlborough Street one day and a girl was walking towards me with just a skirt on. Nothing else. She was walking along the road as if she was out shopping. I don't know what the reason was, she wasn't being photographed or filmed, she was just walking along the street without a care in the world.

JB: That’s the best way to do it.

JS: There was absolutely nothing extraordinary about what she was doing as far as she was concerned.

I would always fit a girl with her facing the mirror because they’d never believe what you were going to say. That happened a lot with Cilla Black. She was so busy wanting to be a “star” that she didn’t know what she wanted. She was always asking if anybody else had worn the same dress.

JS: Quite often people would complain that they'd been to a function and somebody else was wearing the same dress from us. When Princess Anne had her engagement party, we had a dress called Guinevere that had sold terribly well in Harrods. It turned up in all four colours and different sizes on six people at her party. We got a very disgruntled customer ringing up the next day.

DC: What was an average day at work like for you both?

JS: John would be designing every day because he did four collections for Varon and four collections for Bates and for a period he was doing collections for another company. He had his office and workroom on the first floor and we were in a building that was the first Jewish Hotel in London. It had the most beautiful Art Deco ceiling in the showroom, which we actually boarded up.

JB: London was sort of exciting because there were lots of things being tried around you, not just in fashion.

JS: The British Fashion Council started doing breakfast shows for mainly American buyers – I think you were allowed three or four things to show and so you’d find Ossie Clark and somebody else doing exactly the same things.

JB: The politics arrived once the big shows started, and everybody wanted to be in them. We got so fed-up with it that John organised a show himself.

JS: The thing that would irritate me was that everybody seemed to expect somebody else to do something for them, instead of getting off their backsides and doing it! I was great pals with Bill Gibb’s partner, Kate and we thought instead of grumbling about it, why don't we do a show instead of waiting for the Fashion Council to decide what they're going to do? So we picked a day, got hold of Jean Muir and Zandra Rhodes. We had a very strict idea, just 20 garments each, our own models. And the invitation list, if any of the designers objected to anybody on it, they didn't get an invitation. That was it.

DC: So it was a John Bates, Bill Gibb, Jean Muir and Zandra Rhodes show?

JS: Exactly. We had it at Les Ambassadeurs and we had a 300-person limit. We had 350 people inside and still people waiting to get in including American Vogue, so we squeezed them in. I remember people were shouting at me on the street.

JB: Those shows should have gone on. I mean, that caused a lot of interest.

JS: We did it once and then the next season, Ernestine Carter, Prue Glynn and Bea Miller decided they were going to put a show on which then got subsumed into British Fashion Week and all of that nonsense. So we were back to square one.

JB: It's sad, really. I mean, it's better if you have the designers and let them do what they want to do.

DC: Did the four of you all get on? What was Jean like?

JS: Jean was like a sparrow. We thought it'd be nice to give a party for the American press over here, get the designers in and then they can make appointments over a drink. We invited Jean amongst other people, and we had this room that was totally mirrored on one side. Halfway through the party I realised that Jean had turned the whole party around and they were talking to their own reflections. Instead of facing into the party, she had turned out and everybody had turned with her. It was absolutely weird. Jean was very funny; she was very scratchy. She liked me because I was not a designer.

JB: Jean liked to dance and none of us, like Bill and me, ever did so if we went out for dinner she’d always say, “is anybody going to dance then!” and then John would always get up. She was very happy to waltz off with John onto the floor.

JS: She was a very private person and quite demanding but that was fine – she’d had a pretty tough time I think with Jane and Jane, a wholesale house she had before she became Jean Muir. They've got some of those dresses down at Fashion Museum Bath.

JB: They have lots of our pieces – hundreds.

JS: A lot was given by customers after they put a call out for the exhibition they did of us in 2006. They were inundated with dresses but a lot of them had been altered.

Badly!

JS: We turned up and there were about four rails crammed with dresses. They’d come out on a hanger and John would say “NO” to each of them.

DC: And what about the mini dress…

JS: The mini dress really didn't take off until about 1969 – shops would not sell short dresses and even the press wouldn't photograph them. If they did, they photographed the girls kneeling down.

JB: David Bailey always photographed the girls on their knees as if there was something obscene about knees!

JS: There was a woman who worked for the Press Association who would put out a report for all of the papers. When we first started showing, she’d come up to me afterwards and ask, “how many inches above the knee is John during this season?” The buyers would always be nervous about it too and so the first three dresses that he would send out would be really, really high! It was so they would still be in a state of shock by the time the next looks came out and they weren’t that much longer, but they’d buy it.

JB: That's the reason why shops wanted them longer. Because if the customer wanted them short, at least they could make it themselves. If it was already short, they couldn't do very much about it.

DC: Did you have to convince people to get into this shorter length?

Oh, yes. I mean, when we first started out at the top of Bond Street, the Americans came, and they couldn't believe the length of things. And this is the one thing which always disturbs me slightly about Mary Quant getting the kudos for doing the short skirts. She wasn't the first, but she had the money man behind her so she had her own where you could actually buy it. We all did things quite often before her, but we didn't have our own shop to sell it in.

DC: Who do you think was the first the first to do the mini?

JB: Well, it wasn’t the French couturier. I had very short skirts from when we started. But you know, when you start and you do a short skirt, people just look at you as if you're raving mad. My skirts were very, very short. Nobody was shorter than me at the time.

DC: Were buyers scared of any of your more daring looks?

JB: The American companies were, yes. I mean, they had Halston and all of that crowd doing long, so they expected everybody to sort of follow the Americans, which they didn't.

JS: It’s funny what people buy actually. One season the Royal Academy were having a Pompeii exhibition, and I used to go to lunch with the PR girl quite a lot and so I said, “Oh I’ll get John to do a Pompeii group” and so John bought this cream jersey and did a group of dresses. It was in 1976. One took half a yard of fabric. All it was, was a little triangle under the bust – we had a fantastic model, and somebody sent out for a big bunch of grapes. The Evening Standard did a whole page that day so then we had to get the dress made. The guy in the workroom laughed and said: “if you sell any of those, I’ll make them for nothing!” and it walked out of Harvey Nichols! God only knows who bought it, but we made about 300 of those and the guy made them for nothing!

DC: It seems like it was a time when a magazine had a real job to do, you know, people were looking at it to see what they could get. Whereas now the relationship between reader and editor is much more ambiguous.

JS: It’s interesting how effective covers are. John did a cover for Grace Coddington for a Christmas edition of Vogue. He made a pair of sleeves so all you could see were two arms up in the air with lacing around some gloves. The credit said ‘Dress by John Bates’ but there was no dress! I got a very irate telephone call from a customer because she couldn't find it anywhere. She was outraged when I explained that there was no dress to go with the sleeves.

DC: Did you ever feel under pressure to look at what other designers were doing?

JB: Everybody always asked me why I didn't have as much publicity as Mary Quant. She has been a very, very lucky girl. She had her husband who was out there doing everything, he was good looking and he could talk to all the editrixes. And they had a guy who supplied the money for Mary Quant, so she had that shop suddenly and whatever she did, they put it in the window straight away. I had to sell to shops first and wait for them to put my clothes in the window. Mary pushed everything that she was doing on a daily basis. I didn’t mind her doing it, she was a good designer, but it made it very difficult for somebody in my position. I started to get a lot of publicity in Vogue and a lot of it was alongside Mary Quant.

DC: Did you get on with her?

JB: It’s funny, I never knew her really. The best friend we had was Bill Gibb. He was absolutely wonderful. I’d won a Yardley award and had to go to New York in 1968 to judge the next round of the competition. There I saw this fabulous coat. It was Bill’s. They gave the award to another guy called Roger Nelson, who didn’t do the same sort of thing. We came back to London and Barney Wan, who was doing the art direction on Vogue said: “oh come to a party, we’re going to meet Bill Gibb and his partner” and we wouldn’t have gone normally but we did. There was everybody lolling around and there’s this poor guy sitting behind a counter doing things to eat and drink. It was Bill. I said “Why are you behind here, why are you doing all of this. I said if you’re the designer, why aren’t you talking to people?” and he said “Oh, well, somebody’s got to do it.”

DC: And you became friends after that?

JB: I was doing a collection for a very good company, but I wanted to leave to set up Capricorn. I introduced them to Bill, and he got the job and then I told Marit [Allen] that she needed to see him, and she gave him about three full-colour pages for his first collection! But then things went strange, and he left that job because I think he was promised a lot of money to set up on his own.

DC: Did you ever talk to him about work?

We really told him to be careful, but he went on to do those shows at the Albert Hall where all his clothes were shown on actresses. I remember saying to John, the money that has been spent on this is astronomical but what’s it going to do for him? A lot of designers were very against him.

DC: Why?

JB: I always used to think, be careful of designers because there's a sort of feeling of jealousy with some of them, which is not good. Everybody's got to succeed for God's sake. That's why I loved Gérard Pipart. He was so wonderful. In the front of the book there are three sketches of mine from around 1958, which are really his. I was having trouble getting the head to sort of fit onto the neck and the neck to fit onto the shoulder and he said, “Oh, don't worry, darling, there's a special way of doing it!” And he came up with this beautiful sketch, and I went home, and I worked like hell to try and do the same, but I couldn’t.

DC: This was at Herbert Sidon?

JB: Yes, he was a very difficult man, but he loved French couture and he loved Gérard, so he offered to pay all of his bills if he came to London. That’s how I met Gérard because I was already there. He should have had much, much more publicity than he ever had. I think they paid him an enormous amount of money and he was quite happy to work in America. That's what he was after but now and again, you’d see something in Vogue, beautifully balanced, beautifully made and he’d have one page. I always thought that was such a shame.

DC: Well, a lot of success is just about luck, isn’t it?

JB: Sure, but you have to know when the luck has reared up in front of you and grab it.

*