In the window of Louis Vuitton at the corner of London’s New Bond Street and Clifford Street, a Barbie-height alabaster mannequin has tripped and fallen. Sculpted in Nicolas Ghesquière’s Sixties sci-fi silhouette, she taps a mirror with her heel. Her back is turned, her face gazing up at a trompe-l’œil staircase. She has fallen into retrospection.

At Burberry the scene is one of an aloof petting zoo filled with glossy magnolia ostriches, gibbons and pelicans. At Chanel, like its indomitable high-collared creative director, the Eighties mannequins have gone. What is left is a collage shot on the fake rooftops of Paris built inside the Grand Palais. Two fluorescent bin-men sit on smooth stone benches, staring into tiny phones. Givenchy has plastered matte black vinyl to its shopfront. Two ornate metal garden chairs sit empty in the window of Michael Kors beside a weary lemon tree. I pressed my nose up against the haughty glass at Saint Laurent and looked into a void of cold marble and glossy chrome. Bulgari’s pink velvet boxes do not hold any treasure. Hermès quivers with charm, offering a Katy Perry pastel fantasy of architectural elements and amplified silver hardware – a playhouse that now only postmen and Uber drivers will see.

When lockdown was announced, the luxury stores seized their shoes, bags and belts. The high street left theirs in full view. Oxford Circus is now Xanadu, drained. The long stretches of abandoned storefronts remain dressed. Moored in a state with no purpose, the bi-weekly deliveries of new stock and quick-fire changeovers have been disrupted: the fast fashions linger with no warm bodies on which to be pulled. No parties to be twirled around at. No office desks to graze. No spills to suffer — no lives to lead. One-shoulder crimson dresses, single-button cream blazers and knock-off cornflower mules await their fate, scorched by the sun like carefree noses in June. Lurid screens still broadcast videos of nubile, tanned bodies locked in a summery dream. A man on a scooter bellows ‘Somebody To Love’ by the Boogie Pimps. Seagulls sip puddles. Tall pink flowers wither behind glass.

These shop windows have become a sombre Vanitas. They are allegories of the long erasure of fashion’s ceremony and purpose. Much of what we revere about fashion has nothing to do with what it has become. Filmmaker Reiner Holzemer’s poignant study of Martin Margiela, In His Own Words captures the shifts that took hold after the designer sold a majority stake to the Italian entrepreneur Renzo Rosso in the early ‘00s. The term ‘Brand Management’ suddenly became the norm. A new marketing department drew up its own collection plans based on sales figures. Keywords like ‘sexy’ and ‘chic’ were introduced so they could be applied to different product categories with ease. Fashion stopped being about the clothes. ‘Even if with the new direction there was a lot of new and fresh energy, there was something very unpleasant going on for quite a while in the fashion system,’ Margiela says. ‘For me, it started when we had to go on the internet the same day as the show was shown. I like the energy that comes with surprise and this energy was completely lost. I felt more and more sad in a certain way. I thought, this is the start of a moment where there are different needs in the fashion world and I am not sure I can feed them.’ He walked away from the house the day of his twentieth anniversary show on 29th September 2008. The merry-go round began to spin too fast and so, Martin Margiela got off.

Even before our lives felt like DVD extras from Safe, Todd Haynes’s 1995 melodrama about dry coughing and conspiracy theories, health fads and environmental disease, I had noticed how designers began to initiate critiques of consumerism with every season. At a talk hosted inside a pop-up shop in Berlin, the photographer and co-founder of the menswear label GmbH, Benjamin Alexander Huseby calmly said that ‘we need to end capitalism,’ whilst bundling us into his latest fleece jackets with curved seams. Everyone ate cheesecake. But now that clothes-shopping has been deemed inessential, I receive daily press releases from brands that commit to producing new garments in sustainable ways, PR offices eager to share their riff on loungewear and brands touting discount codes.

We’re all functioning with a new-fangled high-tech anxiety that worries about the self and the social order in chorus. Does the world need another dress, I wonder? A great fucking trouser? Where does Balenciaga’s check and houndstooth double-face wool-blend wrap coat fit into what’s happening right now? Where do Gucci’s GG Marmont metallic-leather block-heel sandals stand in all this?

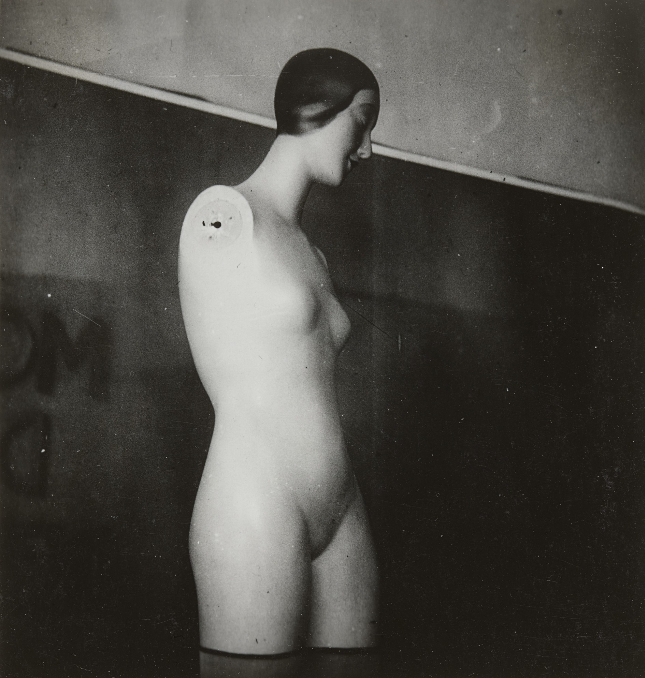

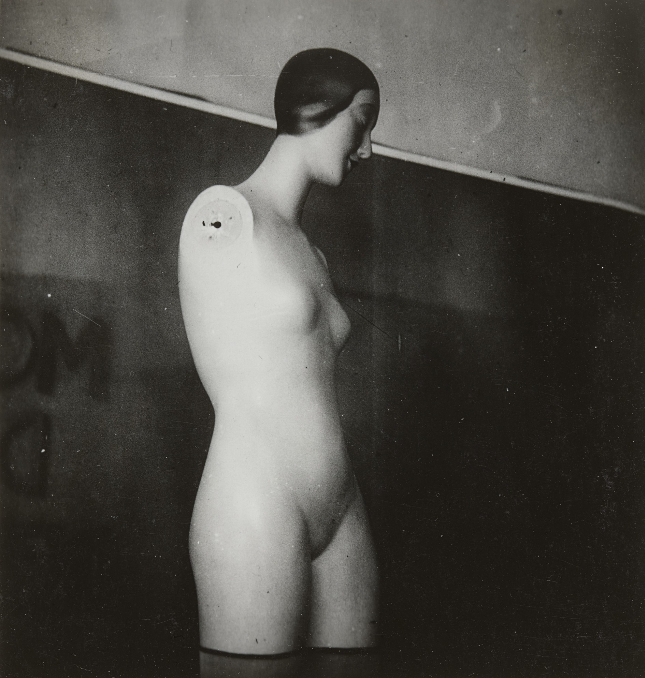

Approaching Marble Arch, I thought about Lynn Hershman’s 25 Windows, a Portrait/Project for Bonwit Teller. In 1976, the artist took over all of the department store’s Fifth Avenue windows, installing a series of tableaux vivants that were part social commentary and part fashion parade. Street theatre: in one, a male mannequin aims a pistol at a love rival, further down a body is coyly turned away from us underneath a still shower. In another, a mannequin is posed with her hand crashing through the glass that passers-by reach out and hold. Hershman’s project encapsulates the grit, danger and glamour of 1970s New York (the windows are Guy Bourdin newsreels come to still-life) but also the social commentary that fashion delivers through fantasy. The endless gifs of Naomi Campbell toting a gun at Versace’s S/S 1998 menswear show whilst wearing a pink crystal mesh dress, or the sharing of Shalom Harlow as victim of two Pygmalion robots in Alexander McQueen’s S/S 1999 show attest to that. Fashion needs to be embodied, it needs to have something to say. Cathy Horyn said in her 2012 interview with Hershman that the artist, ‘believes there is still the opportunity for stores “to deal with the moral and political issues of today” — although she suspects that most people are looking at their cellphones rather than at windows.’ The naked store window publicises Fashion’s vulnerability; the millions of garment workers, textile growers, stylists, photographers, magazine editors, store owners, button sewers, suddenly all left with no work to do. Left to find new ways of existing.

The word ‘unprecedented’ is the hook in the battle cry for political survival during these – unprecedented – times. Amongst the deaths, the sickness, the panic, the stockpiling, the zooming, the virtual gallery tours, the endless requests for Facetime, the handwashing, the dread, is a violent longing for wisdom. Each and every morning we wake to fresh podcasts, emails and PDFS, almost manic in their exhortations of what Fashion needs to learn. ‘It’s Time to Rewire the Fashion Industry’ the Business of Fashion announces. In The Guardian, Tamsin Blanchard asks: ‘Can a greener, fairer fashion industry emerge from crisis?’ suggesting that this unwelcome interruption is bringing ‘a new sense of connectedness, responsibility and empathy’ – if you know where to look for it.

At Dior, the white linen blinds are down. In self-isolated purgatory, we begin to question our need for material things. The theatre is closed, the system stalled. We consider this bloated trade that riffs off a manufactured, manicured need. We think about how much space we take up in the world, how much we miss each other. How much of what we knew will return to the empty window?