Inside the UK’s Brilliant

New Grace Jones Exhibition

Who is it?

Artist and performer Grace Jones skewers the vanity of identity politics – in her image lies sexual potency, gender play, fashion mannequin, Afrofuturism, extra-terrestrial, punk performer, flirty chanteuse, Black androgyne. She was intersectionality before the term was coined, but radiates a resistance against classification. In her 2015 biography she writes: ‘I got […] arrested for disorderly conduct. My first official trouble with the authorities. When they tried to take my mug shot at the police station, their camera never worked when I was put in front of it. Perhaps I was too demonic. They tried a few times. It worked when I wasn’t being photographed. As soon as they tried to capture my image, nothing would happen.’ Grace Jones is impossible to hold captive.

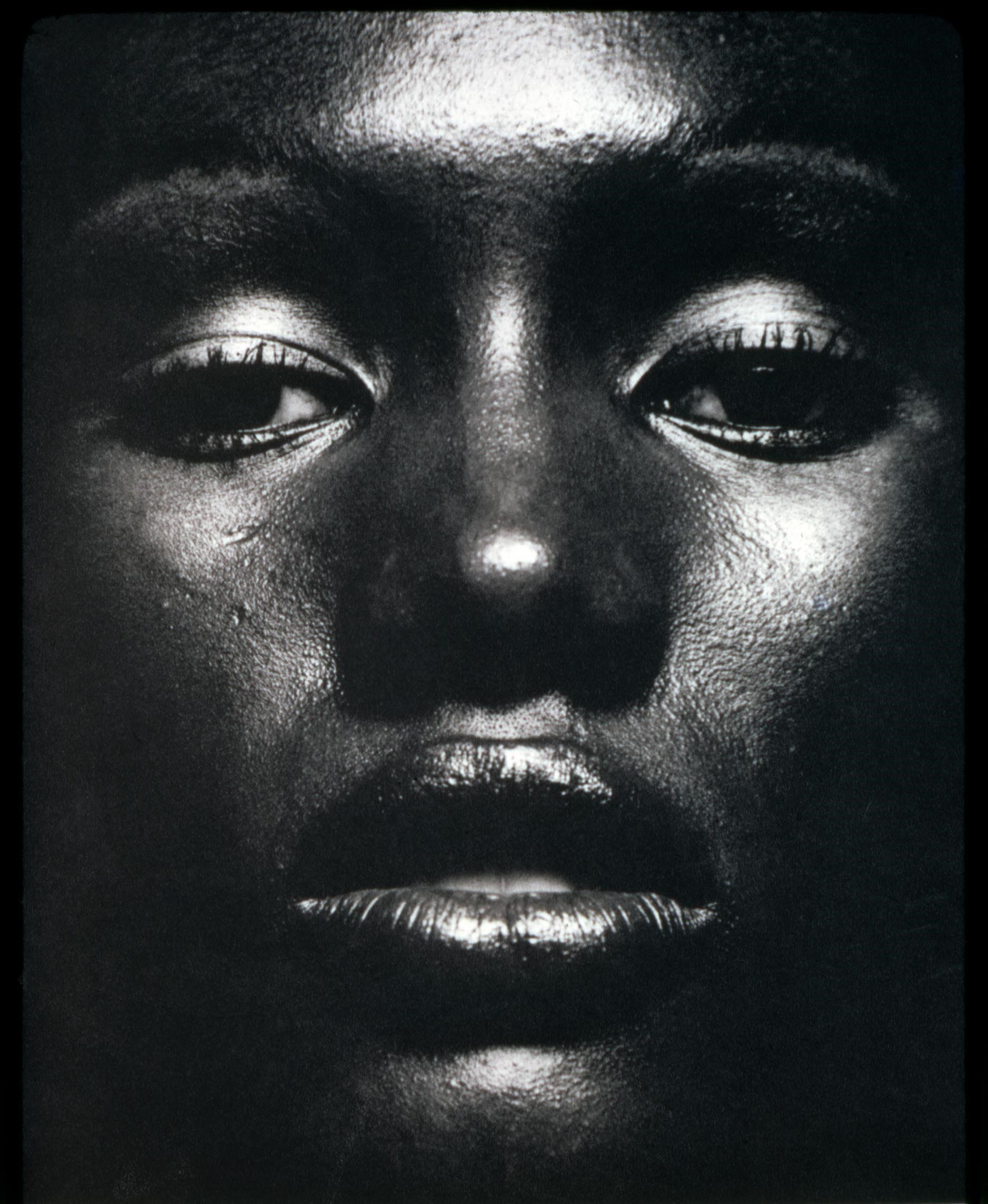

!['Grace Jones NYC' (1970s), Anthony Barboza]()

Grace Before Jones: Camera, Disco, Studio – curated by Cédric Fauq with Olivia Aherne – is a cross between fan-fiction, study and biography. Early on we see Jones lensed by Anthony Barboza for Essence in 1971, sandwiched between psychedelic soul band The Chamber Brothers, wearing a purple brocade shirt with leather pants and big silver jewellery around her waist and neck. Her afro is full and big, her face glossy. Pinned opposite are four pages of model headshots from the Black Beauty Agency (set up by Betty Forray and Dee Gipson in the 1960s) yet Grace who was briefly signed up is notable by her absence, let go after a month because her face ‘didn’t fit’ the black beauty standards of the time. This rebuttal only bolstered her plan to develop her own unique brand of being: ‘I didn’t want to be thought of as ‘black’ and certainly not as ‘negro’, because I instinctively felt that was a box I would be put in that would control me. I didn’t want to be fixed as anything specific […] I wanted to be invisible, unmarked, too elusive to be domesticated.’

!['Grace Jones Mask for Warm Leatherette' (1980), Richard Bernstein]()

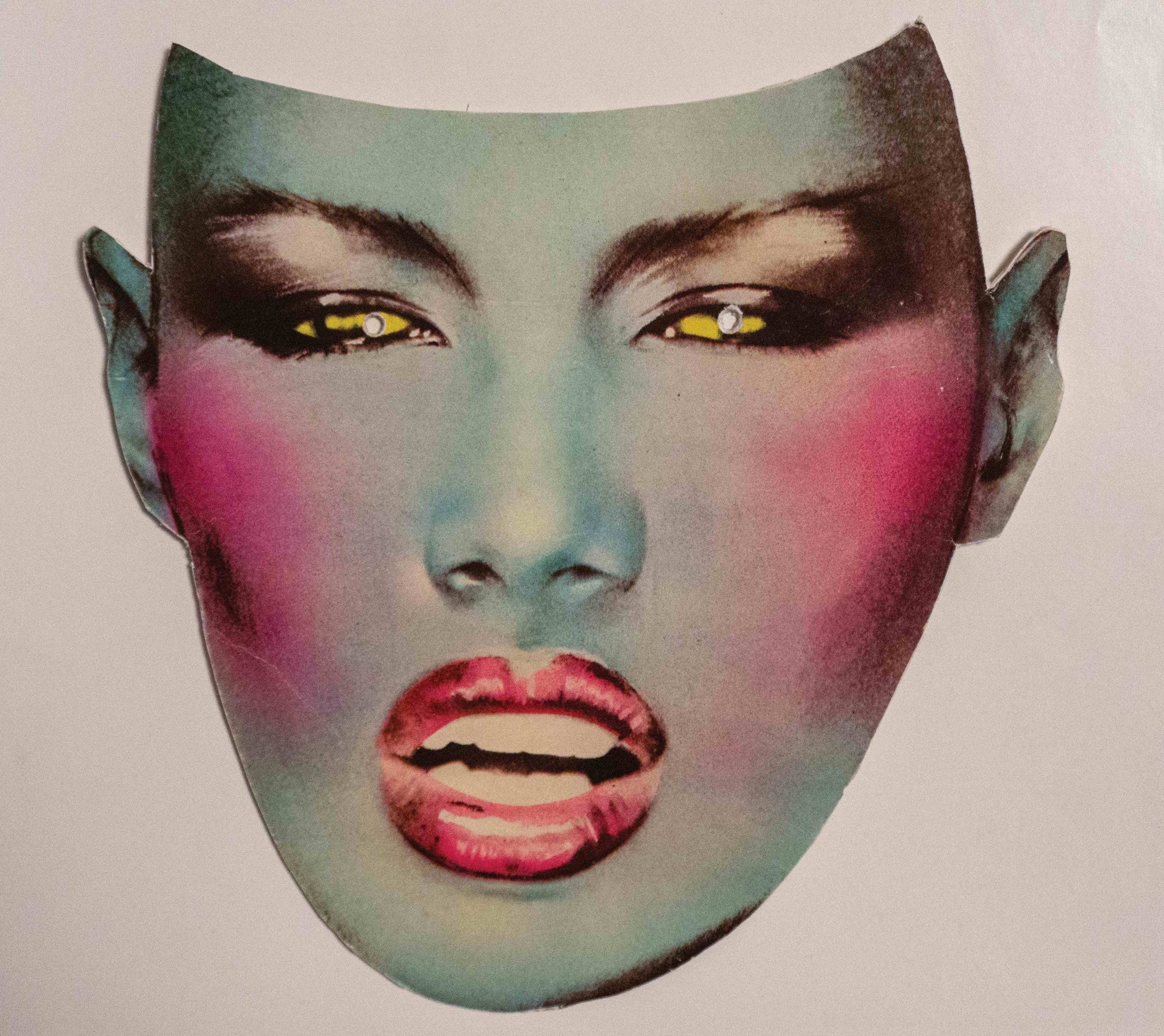

Displayed next to artist Eldzier Cortor’s lyrical mezzotint etchings from the mid 1980s is Richard Bernstein’s Grace Jones Mask for Warm Leatherette (1980) which is sublime in its femme-bot fluidity. It is brutally surreal, yet classically rendered. It is futuristic and frightening, seductive and alien. ‘Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces’, the French artist Claude Cahun wrote in 1930 reflecting on her own artistic practice of self-reinvention – the exact same can be said about Grace Jones.

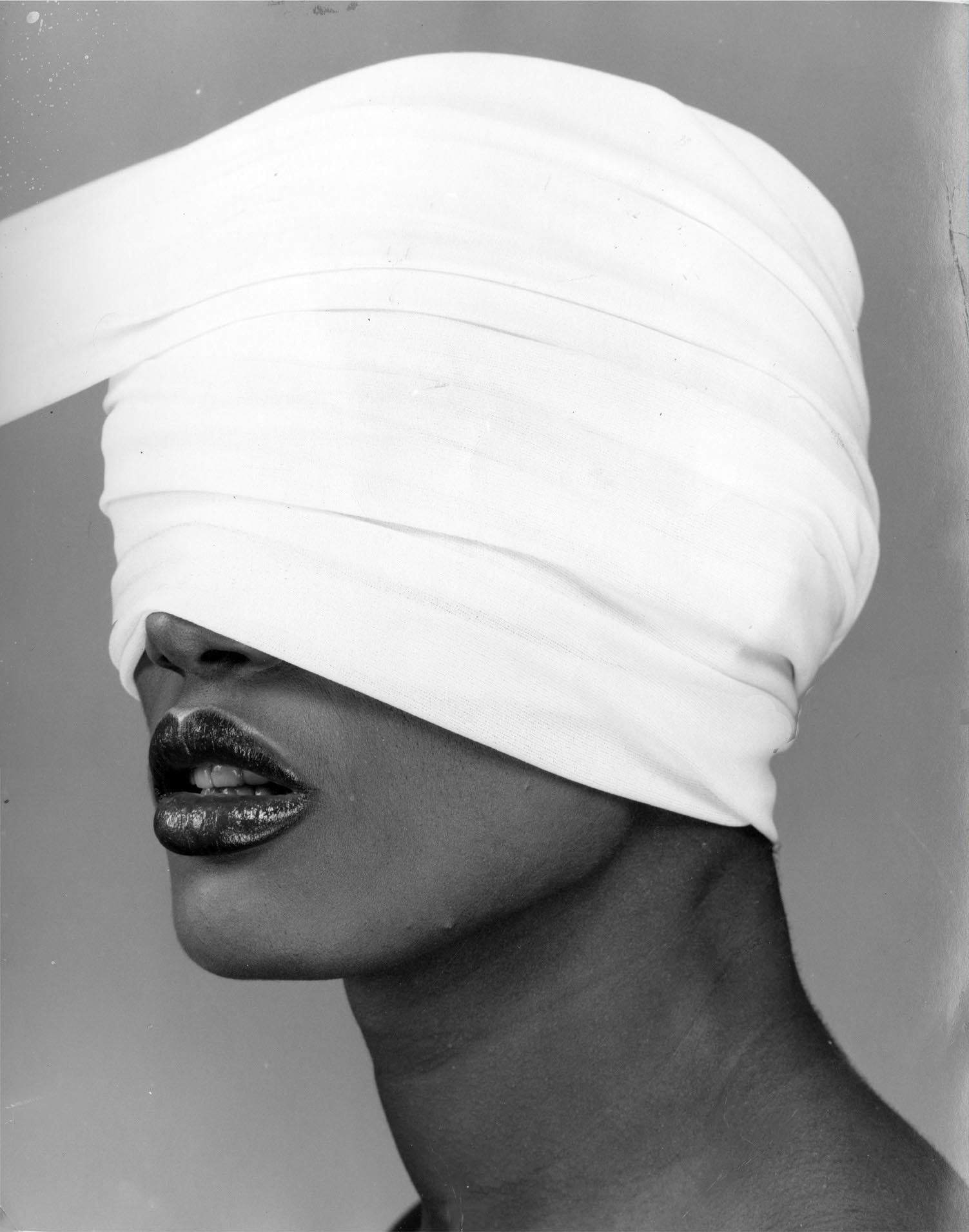

In 1979, her collaborator and then-partner Jean-Paul Goude moulded her face to produce multiple ultra-realist masks intended to be worn by fellow musicians, performers and models. In 1986 Jones stalked 30-minutes late onto an interview with David Letterman clutching a golden ornate mask in front of her face, refusing to put it down. In a clip that can be seen on YouTube, Letterman scolds her for her tardiness. ‘I wish there were 48 hours in the day!’ she playfully laments as the audience jeers for her to reveal her exquisite, real face. She is unapologetic, swinging in her chair part demonic deity, part coquette.

A number of moving image works showcase different Joneses. In William Klein’s In & Out of Fashion (1990) she is effervescent in head-to-toe Alaïa, occasionally holding her hand up to her face, the shock of her red manicure cutting through the screen like a gash. In David Spada’s Grace Jones Live at the Palladium on New Years Eve with Deee-Lite (1991) she’s shrugging into a full chainmail dress looking like a cyborgian Boudicca. In Anton Perich’s Haircut (1978) she is androgyne vamp, speaking in French about domesticity and family life whilst a blade slices through her cropped hair.

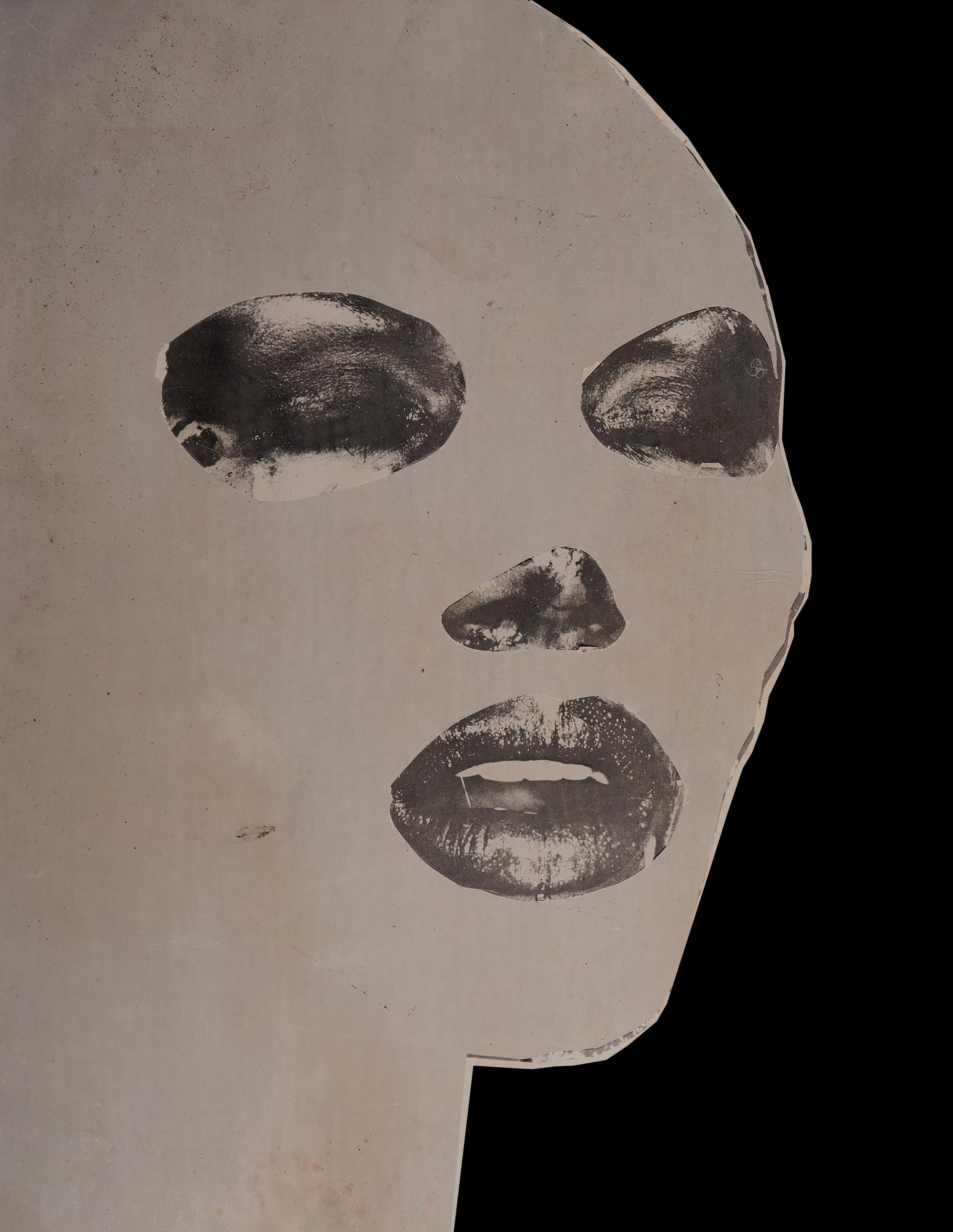

!['Inside Gatefold Art for Fame' (1977), Richard Bernstein]()

!['Grace Jones Photograph for On Your Knees' (1979) Richard Bernstein]()

Why do I want to see it?

2020’s culture war is obsessed with applying order to the ambiguous realms of gender, race and art. This only makes a person like Grace Jones all the more intoxicating. Fauq writes in the accompanying catalogue: ‘I rapidly faced many questions: should it act as a biography? Could such an exhibition include everything audiences would expect from a presentation of this kind? Did we want people to leave the exhibition knowing more about Grace?’ He shows us many images of Jones but none of them are definitive – the visual and aural canonisation of her is presented without hierarchy.

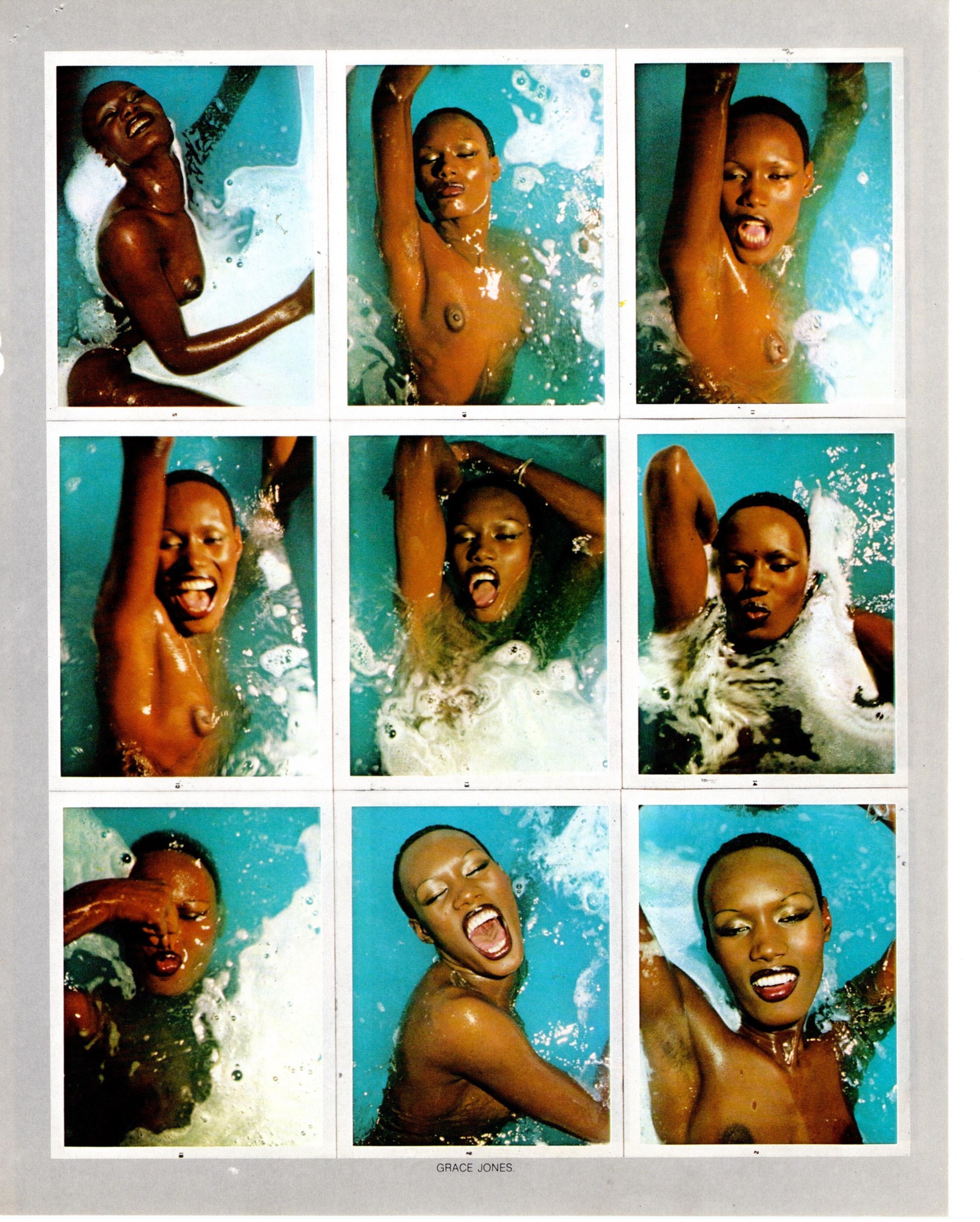

!['Nus Instamatic' (1977), Antonio Lopez]()

Much of the works come full circle: we come across Bernstein’s Grace Jones paper mask again in Meryl Meisler’s photograph of a man wearing it at party on Fire Island in 1977. In episode 2 of Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes (1987), Jones is decked in furs talking to singer Angelo Colon, both of them sitting on steel tubular chairs that remind us of Nicole Wermer’s Untitled Chair (2015) – a fabulously sleazy artwork consisting of a vintage fur coat slung over the back of a modernist chair – which is at the opening of the exhibition.

Also included are several sculptural works by the New York based artist Kayode Ojo, which explore luxury and aesthetic value. His Knockdown Centre (Peaches) (2019) sequin dress slung off a music sheet stand with rhinestone and chandelier teardrop earrings, is an architectural representation of performance. It is disco, hollowed out.

!['LUI Magazine' (1979), Antonio Lopez]()

Where is it?

Jones remains a powerful provocateur in part because she embodies all of the dualities that consistently make people uncomfortable. The show concludes with Catherine McGann’s photograph of her leaving St. Patrick’s Cathedral after Andy Warhol’s memorial in 1987. Aherne says: ‘In that final section, which we have called Curtain Call, is a moment we pause on the Aids crisis to recognise that Grace lost a lot of her collaborators. But she is still very much alive and making music, so it’s not the end.’ Throughout the show she remains a paradox, an unsolved puzzle of beauty and bacchanalia, a refreshing rebuttal of categorisation and conformity.

Grace Before Jones: Camera, Disco, Studio

September 26 2020 - January 3 2021

Nottingham Contemporary