Beyond the humble sandal

The sleepy German town of Görlitz — 60 miles east of Dresden — is a chocolate box of cobbled market squares, dormant fountains and architectural styles from late-gothic to art nouveau. Numerous Hollywood blockbusters have been set against its grand buildings and romantic, pink and cumin facades. A short drive out of its centre, some 90,000 pairs of Birkenstock sandals are manufactured each day, every pair passing through 17 different processes by dedicated human hands. Here 244 years of tradition are played out by a 21st century workforce.

![]()

Birkenstock have seven locations across Germany and it is in Görlitz where the brand’s iconic cork footbeds are finally assembled and produced. Nearby Bernstadt is where the buckles and rivets are certified and the uppers are cut using intelligent software. Both factories are a hub of activity staffed by German and Polish workers, who cross the bridge over the Lusatian Neisse river from the nearby city of Zgorzelec.

![]()

A sandwich of jute, cork and latex, the Birkenstock sandal has inspired consternation over the decades because of its utilitarian appearance, yet today the rest of the world seems desperate to align with its core principles of sustainability, wellbeing and comfort. ‘Products like Birkenstock have this recognition where people don’t know how they feel about them. “Is it nice? Or not nice,” but it is always something deeper. When people start asking questions about products, that’s when things get interesting,’ Klaus Baumann, Birkenstock’s chief sales officer says. ‘When people understand a product immediately, you eat it, you take it for a while and then you forget it. I think it is important when you have questions, when people come up to you and say “I hate your shoes!” That’s great! Because I love them.’

![]()

This polarising shift from seemingly anti-fashion style to hot-ticket item is due in some part to the brand’s pioneering design and unpretentious attitude. It was in the late 1890s that its founder’s great-great-grandson Konrad Birkenstock questioned why the inside of shoes were flat when the soles of our feet aren’t – his answer is there in the many thousands of footbeds made each day that are based on the cast of a healthy foot in the sand. In an age preoccupied with the mechanisation of shopping, sex and friendship, surprisingly every single pair produced is caressed by human hand.

![]()

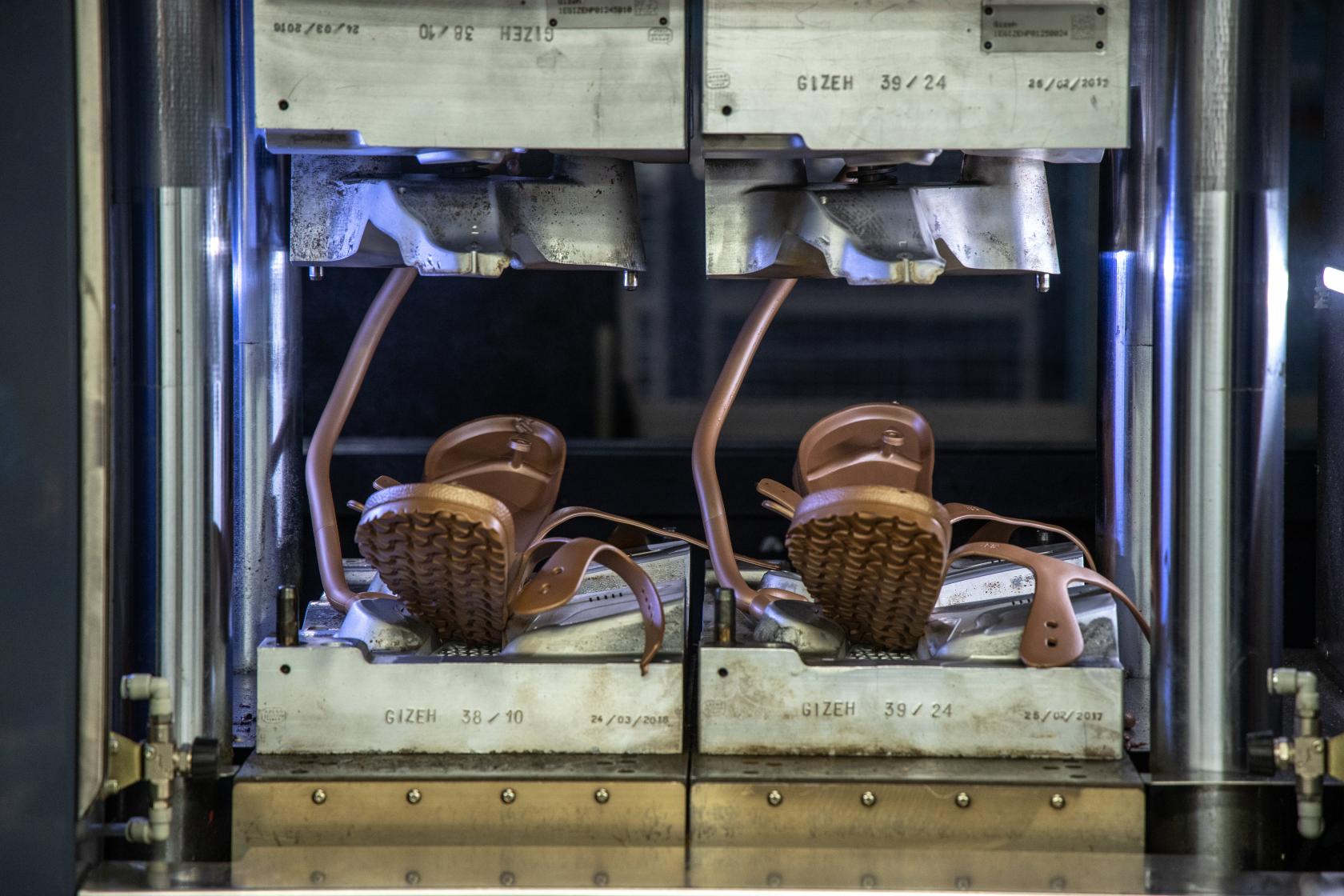

At the factory, channels of silver foil chutes stiffen with the pressure of air pumping through them; mammoth pillows of cork are freshly ground into giant vats, only to be sucked into other sections of the factory via clear, plastic tubing. Giant silver drums containing 30,000 litres of latex thrum in the corner and will need refilling after just two and a half days. The footbeds use two different types of cork, taken from naturally renewable oak trees peeled every 9-12 years in Portugal. They are ground into two weights and mixed together with latex into a gritty gruel-like soup before being baked for several minutes in their mould; these are then turned out by workers standing at large grey tables, checking for residue, trimming and cutting the excess off before the leather upper is attached. At the production line for the brand’s newish, ultra light and highly flexible EVA sandals, playful Jeff Koon-like blobs in bright white, green and blue leap out from their moulds. Only three inches wide, they are stretched over lasts and left to cool to a more recognisable size.

![]()

In the last five years, production capacity at Görlitz has grown from five million to some 30 million pairs. Increase in demand has been fuelled by a wider cultural shift towards wellbeing as well as the arrival of Birkenstock’s more premium line. The 1774 category launched in January 2019 with a focus on special projects and collaborations with entrepreneurs and innovators such as Il Pellicano hotel group, Proenza Schouler, Rick Owens and Valentino. Birkenstock is blissfully aware of its own, authentically cool status; happily outside of fashion yet loved by it. ‘This is such a democratic brand that fashion is a very small part of it,’ Baumann says. ‘Fashion isn’t our total thing but the process of the collaborations is very interesting because you get to find out why people want to talk to you. That is invaluable.’

The approach of working with different designers is less about applying a new look to Birkenstock’s own, it is about a cultural exchange. Often designers will arrive with a certain idea of what they want to do but this, Baumann says, is only where the conversation begins. The factory had to add a new step to its manufacturing process to deal with the excess pony hair clogging the machines that came from building Rick Owens’ styles. ‘First, we ask you to come and see what we do here to change the way you think. In the old days you had designers – designers who worked with their hands – but now a lot of design is coming from computers so people go somewhere and see something and think they can do anything when a lot of it is technically impossible…you have to push them back and explain the process because it isn’t always possible to do exactly what you want. If you want to do that, you need to use a 3D printer,’ Baumann says.

‘When people understand a product immediately, you eat it, you take it for a while and then you forget it. I think it is important when you have questions, when people come up to you and say “I hate your shoes!” That’s great! Because I love them’

— Klaus Baumann, Birkenstock chief sales officer