March 2021

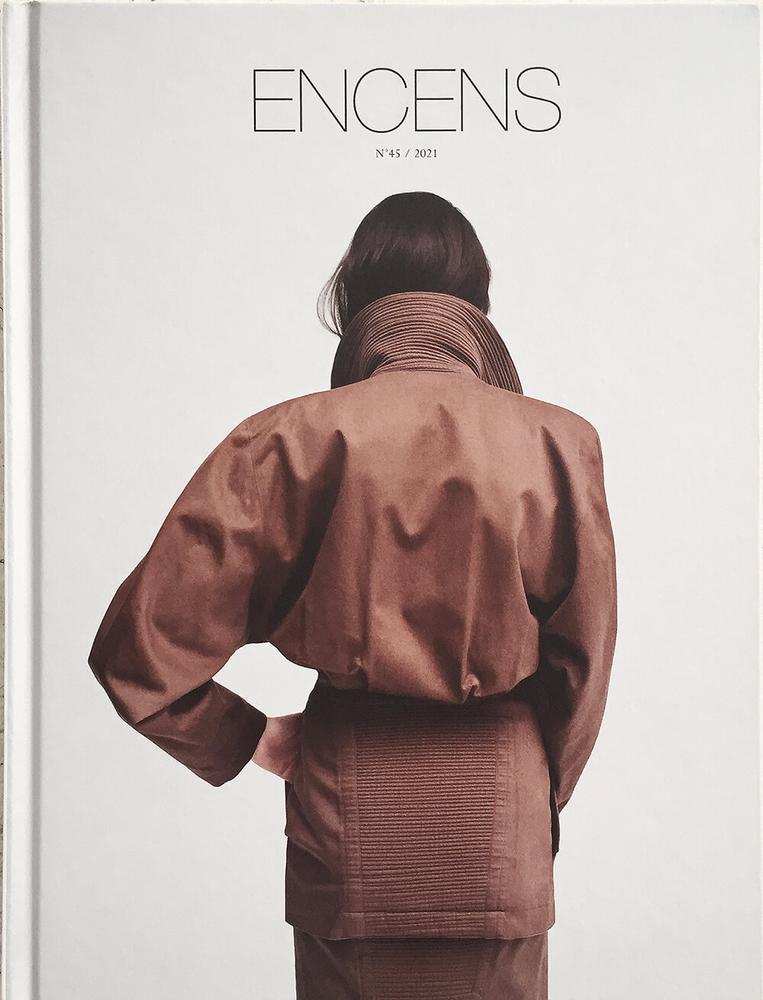

Hed Mayner

Published in Encens N°45

Private Lives

In these restricted times, the cavalier gestures we once performed in private have taken on a pacifying logic. Well-worn elbows now rest listlessly on desks. Stray cat hairs are steadily gathered from thick cashmere, hands rubbed anxiously clean on denim thighs.

I have been thinking about how we wear things if the days drag on with no one to see.

I have been thinking too about a picture Bill Cunningham took of Isabella Blow running around Fashion Week in the early 00s. Draped in Yoshiki Hishinuma’s waxed plastic wind coat made up of multi-coloured boxed shapes, she dashes through a cobbled courtyard as security guards look on in awe. The drama! The theatre! The unfettered glamour of impracticality. The whimsy. The shows! Paris! The picture is a fragment of a fashion industry that is as dead as its noblest auteurs.

![Hed Mayner A/W 2021]()

![Hed Mayner A/W 2021]()

Good clothes mirror the times – in the poetic work of the Israeli designer Hed Mayner there is an ode to performance. With their sculptural largesse, his clothes are just as showy and just as alive as that billowing vampy red, bogey green, deep oxblood and Barbie pink coat. Full of sensual froideur, what he does is confusingly relatable – extreme in its twist on the ordinary. ‘It is something blurry. Harder to understand. The clothes create some kind of distance when you wear them, but it isn’t a distance related to status,’ he says. Mayner’s padded button-down shirt jacket, fitted poncho-trench and 8-pleat herringbone pants obfuscate gender, body and attitude in a way that is often mistaken as aloof. His are clothes you can move in and get dirty with. ‘People in my clothes, they transform, I love seeing it, it’s related to the textures maybe and the fit, but it’s important for me to see that. It’s a person in their body, in their stuff.’

A person in their body, in their stuff.

A year of the same familiar curated faces mediated via screen has made it impossible to observe the small, daily actions that are so instructive to a designer like Mayner. ‘Clothes have become something that is more interior than exterior – something you put on for yourself at home, less for performance. It is really internal,’ he says. The mood around fashion now is not shaped by those attending the shows – we are just casualties of its excesses – fashion is in what people read, how they talk and what they engage with. ‘I’m very interested in interference. Thinking about how people are going to wear the clothes. For me, not travelling this past year was difficult because I need that for perspective, I need it to understand what I am doing.’ Clothes need to have a job to do. They need to have a life. They need to perform.

![Photograph by Cecile Bortoletti]()

After months under lockdown I had become used to seeing only a only handful of people on my daily walk. One bright Wednesday afternoon, as the shops had reopened, I saw groups of girls clattering in cropped sweatshirts, stroking their long hair. I saw a man in a well-worn white cotton t-shirt that had a hole at the nape of the neck. I saw frayed hems on grey jeans polishing bulbous blue sneakers. It was then that I understood what Diana Vreeland meant when she said: ‘The eye has to travel.’ I had missed looking. I had missed seeing clothes out in the wild.

A lot of what Mayner does is unpick the familiar, to take what he sees on the streets of his native Tel Aviv or Paris and reimagine it to create something curiously familial yet off-kilter, ‘honing in on the small space between familiarity and just beyond the expected.’ A year in physical isolation has changed how we use our clothes – perhaps we care less about what they say and more about how they perform. Perhaps we are more grounded to a sense of humanity – one giant swirling mass of people who are scared, confused and re-assessing. ‘I’ve always had this distance – from everybody, from the industry, from my co-workers who are in Paris, but I am not an isolated person,’ Mayner says. ‘I have a strong will to be a part of the world and the clothes are about telling stories, communicating, giving, all these kinds of things.’ There is always a dynamic between the interior and the exterior in his clothes – space between the body and the material, the back and the front.

The Hed Mayner look interrupts the line in a crowd. It doesn’t shout. It speaks confidently of a wearer who is content. ‘It’s also a very giving attitude, dressing in this way. You dress like this because in a way you care – it’s important for you that your clothes tell a story, it’s important for you to communicate. And at the same time to have some distance to protect yourself. You want to be part of the world, yet you always feel this disconnection from it. So, you search for a way to express yourself in relation to other people.’

Roomy separates in a rainbow of taupes, beiges and greys have become a kind of Corona chic for the international elite. Sexless square cut cashmere knits, minimalist loose-fitting pants, soft leather or shearling slippers – a facsimile of a look that was once the reserve of the more cerebral dresser. Mayner says, ‘these labels that have this kind of look are often seen as very conservative but that’s not what I am interested in. I am interested in the new, always.’ The oversize proportions of Mayner’s clothes come from his interest in borrowed style – they look like pieces that you’ve found and put on. They have attitude, there is a gesture already imposed in the clothes. It’s a kind of minimalism that is not minimalist. To wear his tailored double-breasted blazer which sits high on the chest but drops vividly at the shoulder is to invite conversation. You encourage furtive glances. ‘I never really felt comfortable when people use the term ‘minimalism’ to describe what I am doing,’ he says. ‘I don’t seek for the most essential white shirt, with mine there’s always a mistake in it. There’s a human element in it. I am not searching for perfection.’

In eccentricity of any kind there is a spirit of generosity. ‘It’s the magic. The alchemy. How something transforms into something new – that’s what I am into. To take something that is familiar and make it look different is part of the approach but at the same time to keep it complete, with a quietness. Maybe it is grounded in a reality or humanity, but it’s also about projecting something beyond what you can see… a feeling,’ Mayner says. It’s there in the crease of an elbow, the warmth of a collar. The snap of a button. It is in the heart of the clothes.