Tenderness

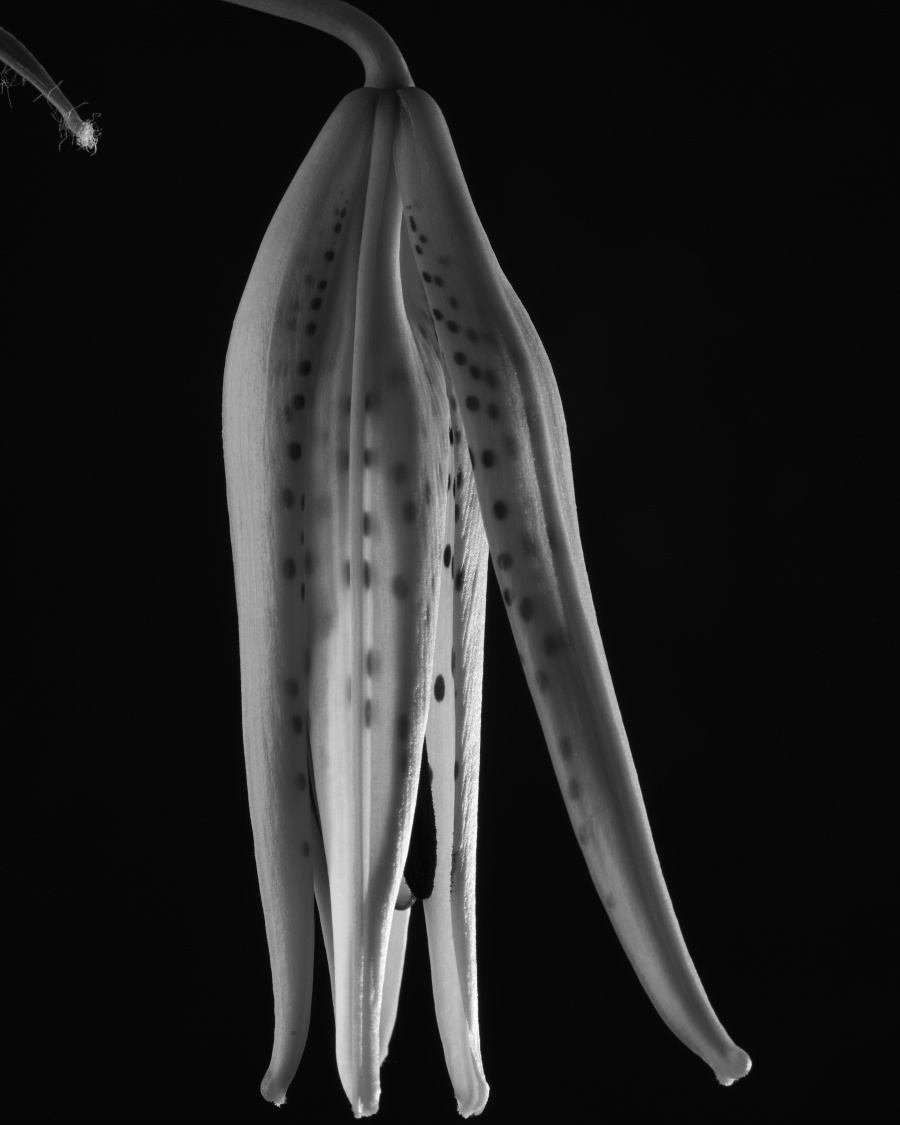

![Photography by Blommers and Schumm]()

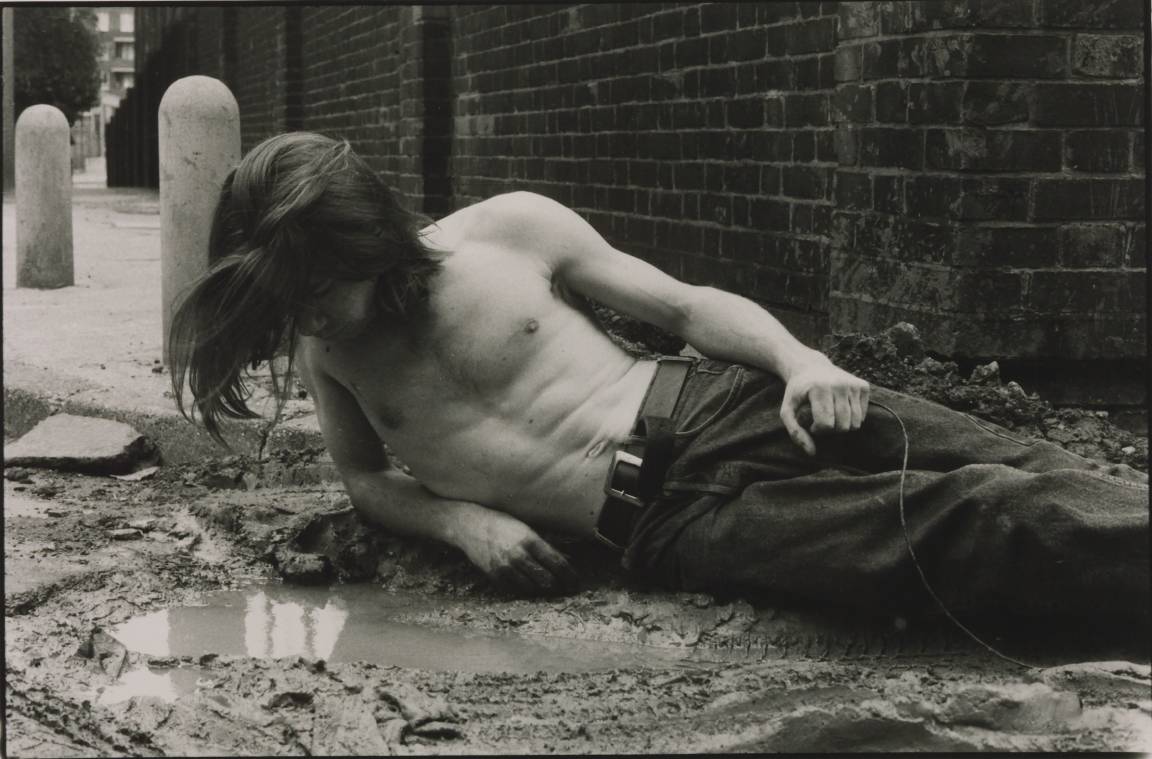

Flowers are helplessly symbolic. Cut fresh stems, slotted into cool water-filled crystal vases, endure as perilous effigies of our existence. Beside hospital beds they give solace; on vacant family dining tables they scatter joy. Passed from one hand to another they commit to kinship; loosely tied to metal railings, they ask for remembrance. In their loveliness is tenderness, in their tenderness brutality.

During lockdown, the windows of luxury stores across the city were defined not by their darkened, emptied interiors but the unkempt withered stems, burnt petals and dried vases standing within them as capitalism stalled. Grandiose floral arrangements adorning the fronts of unoccupied hotels dropped to nothing; muscular green plants commandeering the entrances to multinational corporations drooped and expired. Flowers became the prolific idols of 2020’s unyielding spring.

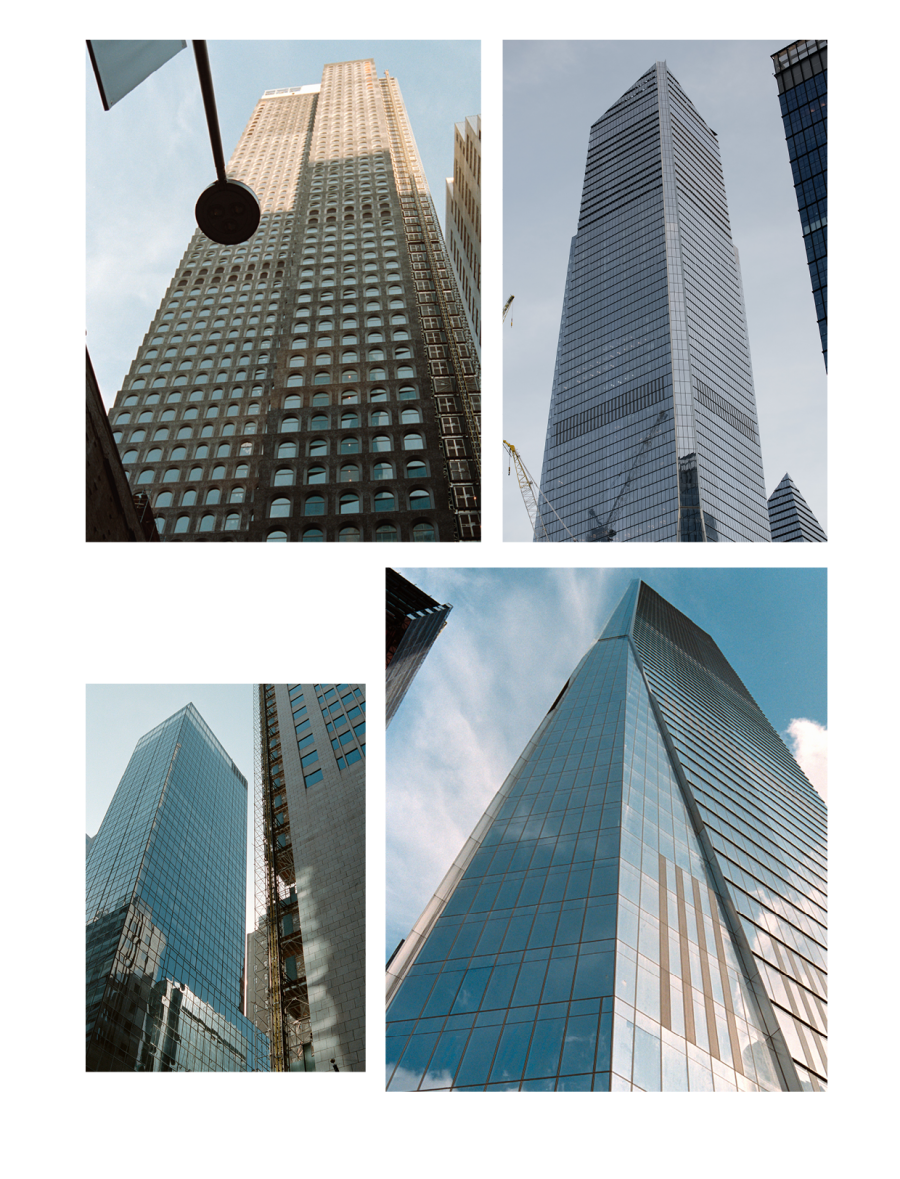

A plant is a city. The stem is the support, the roots are the underground system for nurturing and nutrients, the leaves feed on sunlight and through transpiration allow the loss of water vapor to cool the plant. Through respiration it converts sugars and starches to energy, which help it to stay alive. It is difficult not to find a parallel with the increased sense of community we have forged in the past months – caring for a plant, like living in a civilised society, requires compassion. Our repeated acts of kindness, from washing and clapping hands, shopping for neighbours, even distancing ourselves from each other, are ways of tending to our own ecosystem – of keeping things alive.

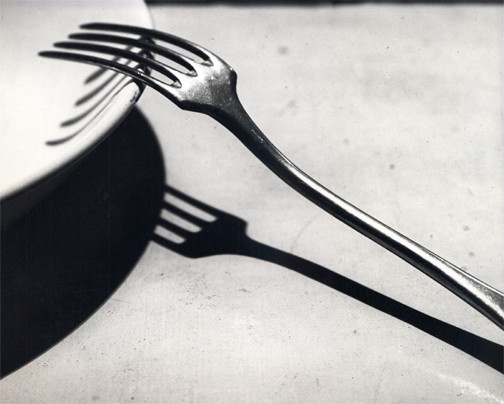

‘Nature educates us into beauty and inwardness and is a source of the most noble pleasure,’ Karl Blossfeldt, teacher at the Royal Arts Museum in Berlin said upon publication of his book Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature) in 1928. Filled with stark, graphic portraits of flora, the catalogue was intended to be a guide for industrial and commercial designers but is today celebrated as an example of early modernist photography and aesthetic philosophy. Urformen der Kunst helped its readers to look at the natural world with a new eye, linking flowers to fences, petals to patterns and stamen to spires. It is precisely in nature’s engineered beauty that we find not only the inspiration to build, but the courage to live.

Despite her most famous works being of lilies, orchids and petunias, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe once admitted ‘I hate flowers. I paint them because they’re cheaper than models and they don’t move.’