Lessons We Can Learn

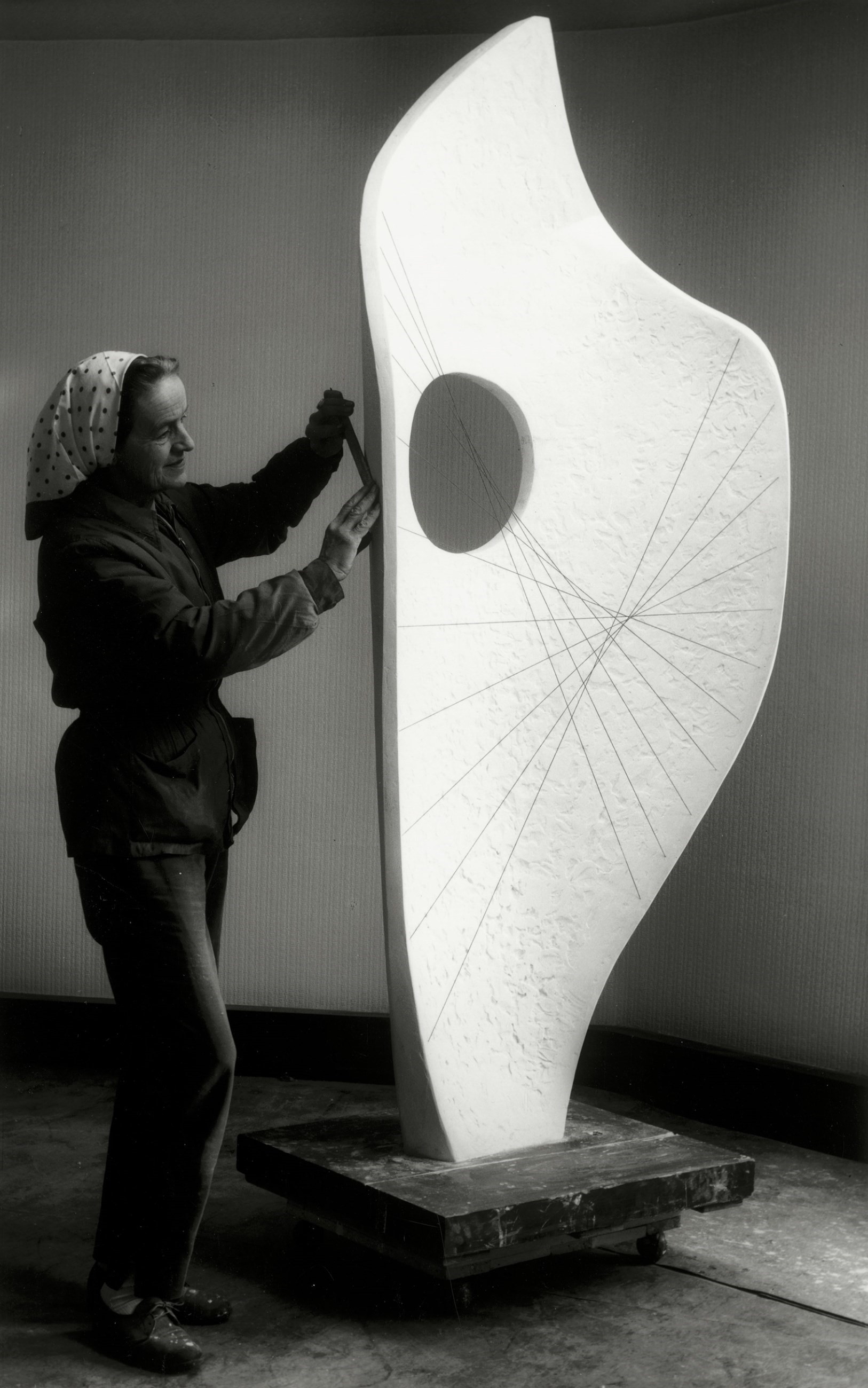

There are all manner of morals lurking behind the surface of art. Most important are those works that remind us of our place in the world. For this, we should look no further than the British sculptor Barbara Hepworth. Hepworth believed in the power of art to shape society, inspired by the groupings of totemic stones found dotted across the Cornish landscape.

‘Whenever I am embraced by land and seascape I draw ideas for new sculptures; new forms to touch and walk around, new people to embrace, with an exactitude of form that those without sight can hold and realise…It is essentially practical and passionate,’ she said in 1966.

The first major London exhibition of her work for almost 50 years opens at Tate Britain on 24 June. From Hepworth’s earliest surviving carvings to the large-scale bronzes of the 1960s we are able to consider how the intangible mystery of feelings co-exists with the fleshly realities of everyday life.

MAKE MORE SPACE FOR NATURE

Alongside her second husband, the painter Ben Nicholson, Hepworth became a key figure in the development of the artists’ colony in St Ives. Its influence on her work is best seen in the accompanying catalogue to Tate’s 1985 exhibition St Ives: Twenty Five Years of Painting, Sculpture and Pottery.

For most of us, our busy, saturated lives leave little space for nature. The artists who have lived and worked in West Cornwall often speak of the sea and its ever-changing colour from slate grey to plum to deep ink blue and moss. To her friend, the critic Herbert Read, Hepworth once wrote: ‘Imagine the critic having to climb a hill, or walk a mile through a forest … to see a sculpture.’ Hepworth loved her sculptures to be seen outside of the museum, reacting to the light and the seasons.

BELIEVE IN THE POWER OF ART

The new artistic bodies that established themselves after the war – the Arts Council and the British Council – gave a new democratic principle for sculpture. Consequently, today you can find a Hepworth everywhere from Holland Park to Wolverhampton.

Hepworth’s enthusiasm for public sculpture in the 1950s might relate to the role that democratic art had in the thinking of the Abstraction-Création group. Hepworth joined the group in the 1930s after several visits to Paris where she met leading artists like Picasso, Naum Gabo and Constantin Brancusi.

Hepworth hoped that her art presented the possibility of change in society. The erect stones in Group I (Concourse) (1951) were inspired by the piazzas she saw in Italy; the totems that make up Conversation with Magic Stones (1973) and the 6.4 meter high Single Form (1961-64) which stands outside the United Nations Building in New York, all suggest concord. As Dore Ashton wrote in the catalogue to Hepworth’s Conversations show at Marlborough Gallery in 1973, her work is about the ‘vision of a cosmos’ – a vision for collective living, despite the chaos that abounds.

CAN YOU HAVE IT ALL?

Steering clear of the facile 2011 American comedy film I Don't Know How She Does It (based on Allison Pearson's novel of the same name) the question of how a woman might balance the demands of a family whilst having any sort of career – let alone an artistic one – is not likely to go away anytime soon. It is a subject that Hepworth tackled head on.

She had a son with her first husband, the sculptor John Skeaping in 1929 although their marriage didn’t last. In 1931 Hepworth met Nicholson who shared her interest and passion for pure abstraction. They went on to have triplets three years later. In letters written to Nicholson, Hepworth worried most about ‘being separated from carving by nurses, undernurses and cooks.’ She was not about to replace her chisel with a rattle.

Some writing about Hepworth can present her as a tough, selfish mother. The triplets were farmed out to a Hampstead nursery-training college and were later given scholarships at the progressive boarding school Dartington Hall. The tenacity however with which she developed her career is impressive: ‘we shall be twice as much use to these babies if we are producing good work,’ she wrote in letters that are today nestled in the Tate Archives.

CELEBRATE THE SEXES

Hepworth speaking on 20 March 1950:

‘It is often stated that women’s work is best when it accepts the limitations of their sex and is most feminine; but that by being feminine it has never scaled the upper reaches of achievement in art and presumably never will. This belief in the inevitable inferiority of women’s art presupposes a competitive element between the sexes. I do not believe that women are in competition with men. I believe that they have a sensibility, a perception and a contribution to make which is complimentary to the masculine and which completes the total experience of life. If this is accepted, instead of feeling cheated because a woman is not a man, it becomes possible to enrich one’s experience by the contemplation of bivalent expression of idea.’

USE YOUR BODY TO FEEL SCULPTURE

In an interview in 1972 Hepworth suggests that we give her sculptures a ‘pat’ when viewing them. She was talking in particular about The Family of Man – a group of 9 individual bronze sculptures completed in 1970. One of her final works, the sculptures represent ancestors, two parents, bride and bridegroom, a youth, a young girl and something which she resolves as the ‘ultimate form.’

‘I think every person looking at a sculpture should use his own body. You can’t look at a sculpture if you’re going to stand stiff as a ramrod and stare at it. With a sculpture you must walk around it, bend towards it, touch it, walk away from it.’ she says.