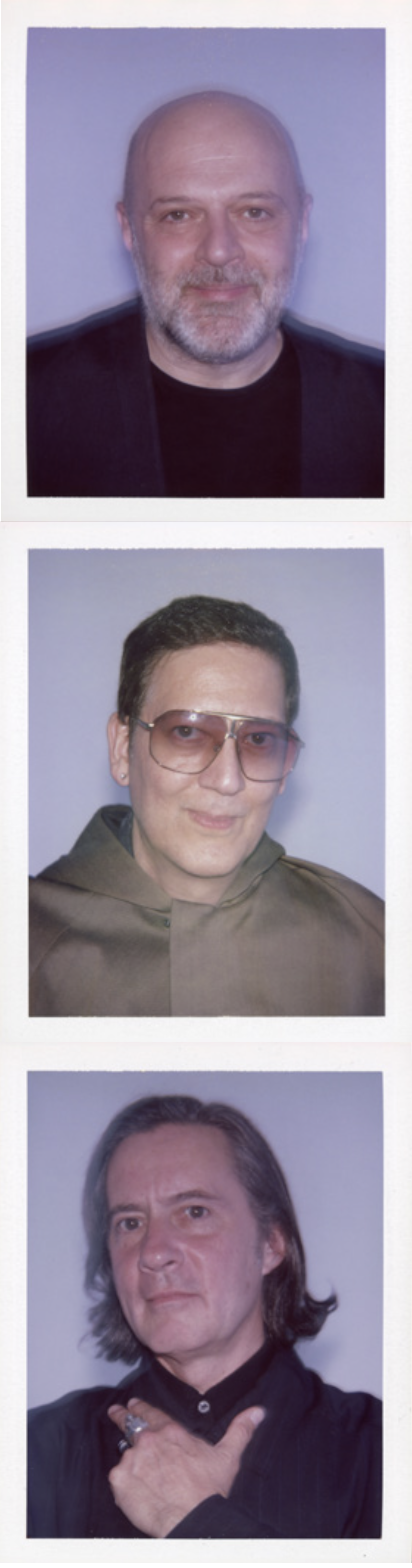

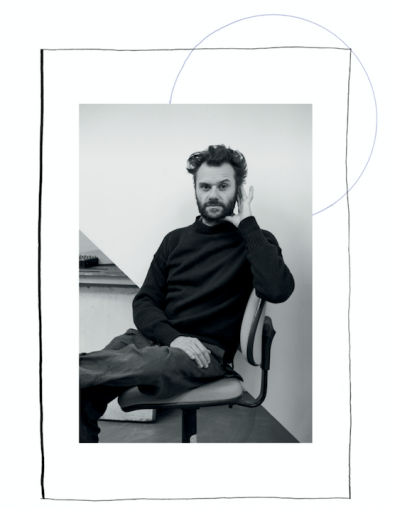

The Artist Is the Messenger

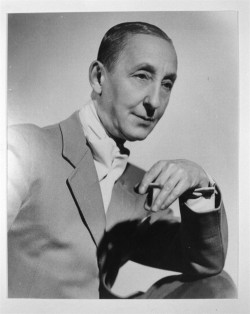

Who Shoots Himself

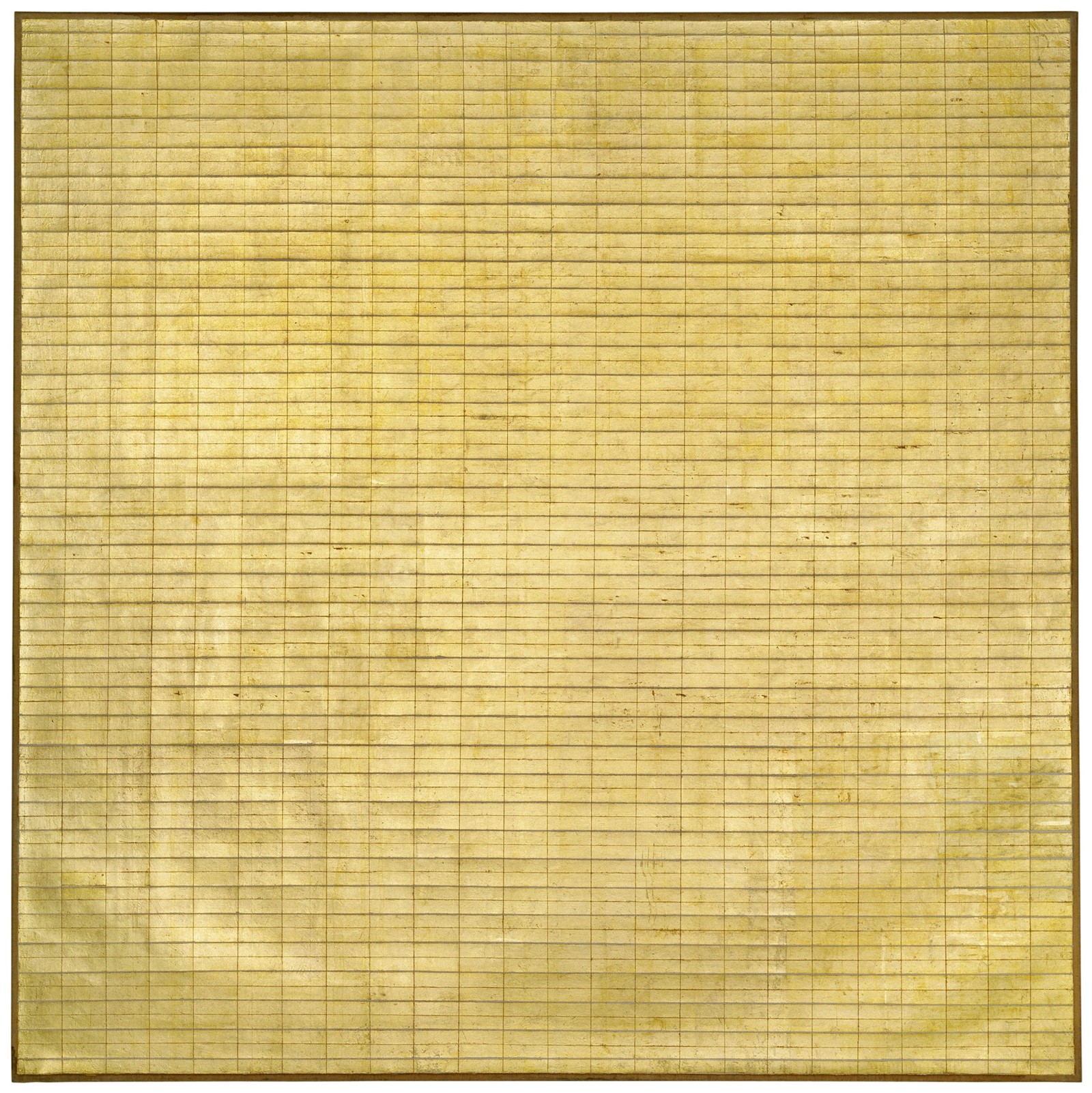

‘This era needs a way of art-making to inspire, stir and destroy our thinking.’ So says Chinese multimedia artist Xu Zhen, who has turned Andy Warhol’s bacchanalian Factory into corporate reality. Since the late 1990s, he has parodied the complexities of being a maker of art in a culture goaded by commerce. His large-scale installations, sculptures and performance works are socio-political provocations disguised as pop art. Ten years ago Zhen transformed himself into a CEO with the creation of MadeIn Company – an enterprise focused on curatorial production, research and publications that forms much of his own artistic practice. China is now the world’s third largest art market after the US and the UK, and there is a lot of money to be made, particularly in Zhen’s native city of Shanghai. His gallery is both a showroom of art product and the meeting place for international artists. For him, ‘the creation of art is almost the same as Internet start-up companies that finance quickly before going public and grow rapidly.’ Today, the template of ‘company and brand is more real’ than the traditional role of the artist as outsider. ‘It’s like a doctor who is terminally ill and just as desperate as everyone else for a cure.’ The artist is the messenger who shoots himself.

MadeIn Company isn’t limited to artistic output alone and includes the media platform Artbaba Internet forum, which brings artists together to bicker and bond over the making and selling of art. ‘Artbaba has maintained the basic requirements of directness, chaos, non-consensus and spontaneity. It is like an indiscriminately talkative child,’ he says. ‘Not pursuing political correctness has always been one of my reasons for staying alive.’

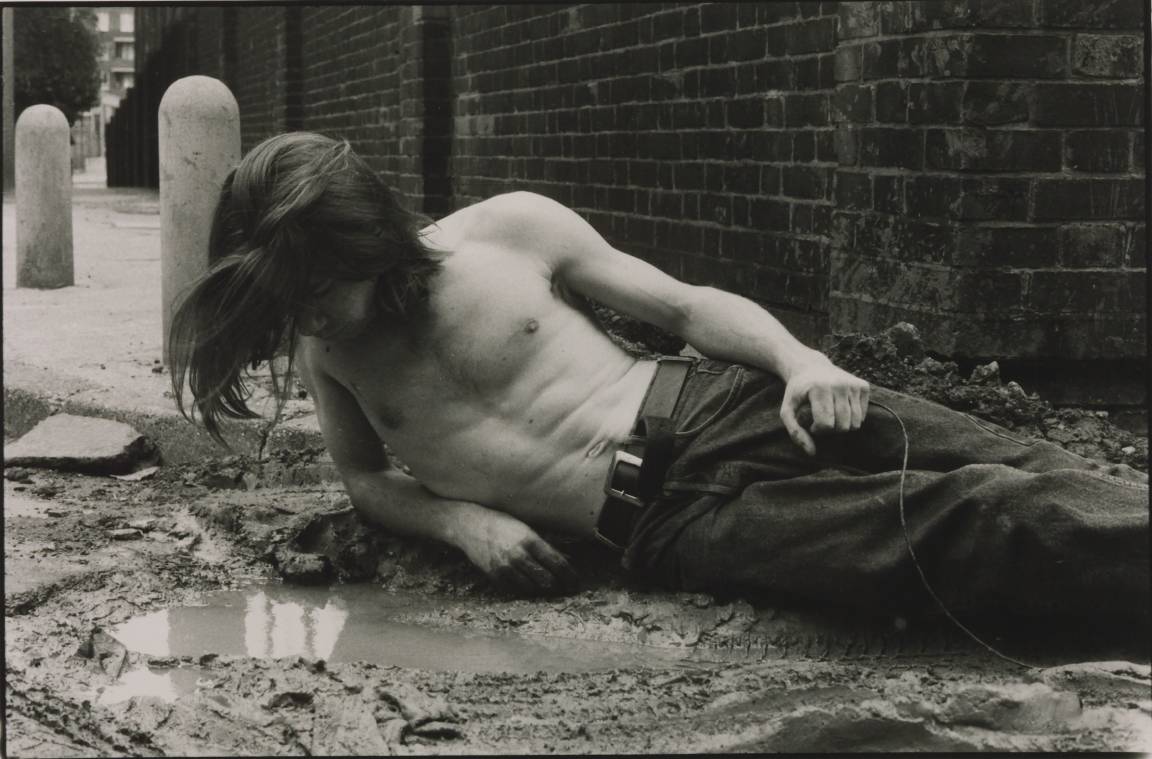

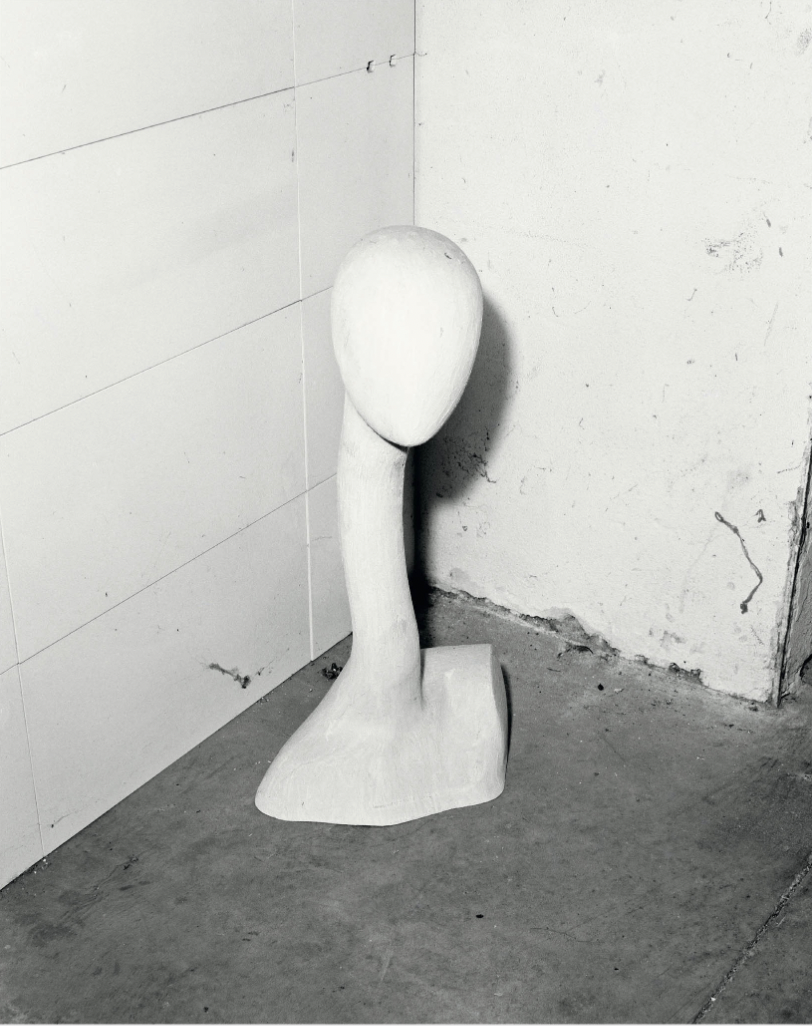

Zhen first unveiled his ‘living sculpture’ In Just a Blink of an Eye in 2005. It has recently been acquired by LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Four actors are frozen in mid-air as if about to crash to the ground; they appear to be waxworks until the blink of an eye or the twitch of a nose reveals the truth. ‘It jarringly forces viewers to question the laws of physics … and it’s something of a meditation on stillness and the fluidity of time. Among other things,’ Deborah Vankin wrote in The Los Angeles Times. These ‘other things’ are what makes the work such a powerful lamentation on the loss of autonomy. The meaning of In Just a Blink of an Eye is ruled by its surroundings, its casting and its timing.

When it was first shown in China it alluded to the instability of working conditions in factories reliant on orders from the West. At the same time, the government revalued the Yuan, ushering in a volatile global economy, putting international trade at risk. The piece has been shown all over the world and each time, its narrative is re-written and new ideas are projected onto it. It is brilliantly malleable.

‘Not pursuing political correctness has always been one of my reasons for staying alive.’