Every Last Breath

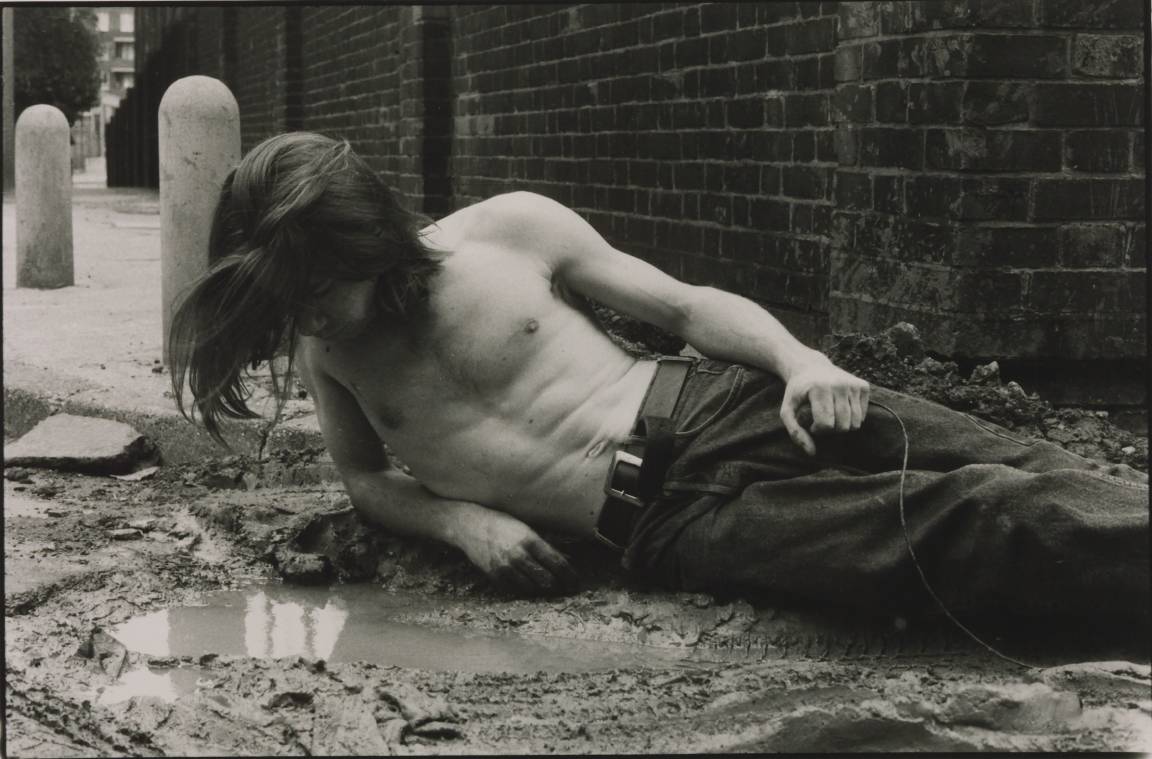

Much has been yammered about Instagram and its devilish ways. It has bribed a generation with the promise of democracy and visibility, yet birthed a malaise of self obsession and self loathing. Photostreams are a parade of pity: I am here looking available because I was just rejected. I am here looking thin and tanned and happy when I think I am heavy, pallid and sad. Pictures are worth less than the words it takes to denounce them because they say it all, in an instant.

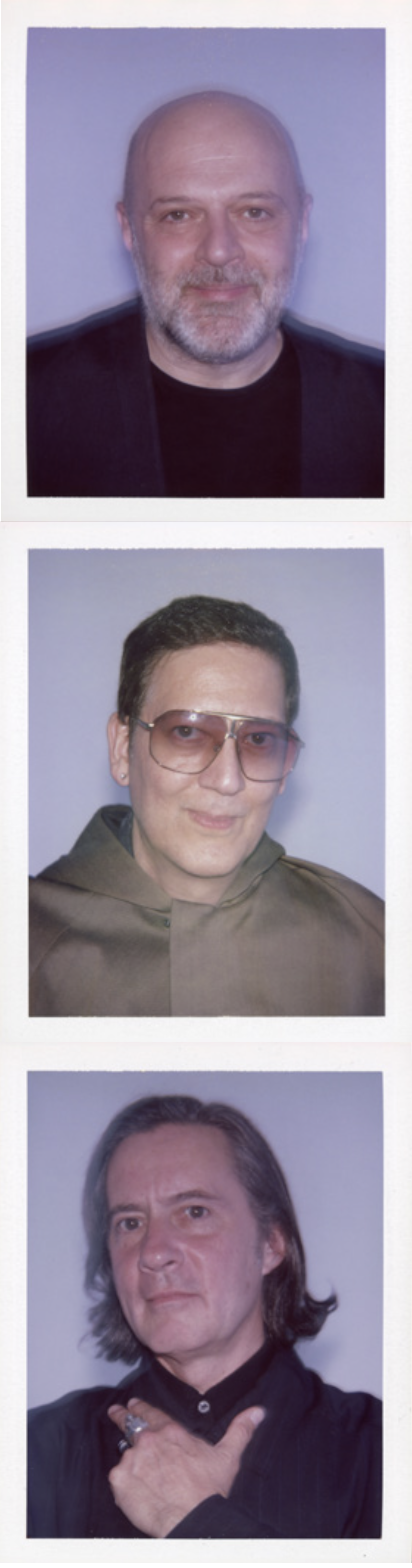

Warholian attempts to claim our 15 minutes have rendered basic human interaction an irritant distraction, a chaos outside the clipping of our lives into cohesive lots of lonely, gossamer frames. ‘Now many people want the contrary: to be invisible if only for fifteen minutes,’ Hito Steryl wrote in her 2012 essay The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation. We have entered a peak-paparazzi, peak-voyeurism, peak-exhibitionist time. We have got what we deserved.

‘The chicest thing,’ designer Phoebe Philo told the Evening Standard in 2013, ‘is when you don’t exist on Google. God, I would love to be that person!’ Today there are a crop of Instagram accounts organised in her name. ‘I Miss Phoebe’, ‘RESPECT THE É’ and ‘BRING BACK PHILO’ were printed across cotton t-shirts upon her departure from the Céline fashion house in waspish panic. Instagram emboldens this idea that everything is important, all of us are important. All of us matter. It is a rolling, blinding billboard of the last 60 seconds. The shores of the internet are awash with what Steryl decrees as ‘the spam of the earth’ - images stay on hard drives much longer than they will be in front of our eyes. They are clipped memories of an imagined, algorithmically aestheticized life. Unreal in their familiarity.

Content ad infinitum. A swipe and a tap promise a surge of pointless, beautiful data. Each of us is engaged in the mucky minutiae of breathing, spitting, crying and bleeding – now we have a way to authenticate it. Instagram has spawned a pop narrative that we celebrate ourselves 24/7. It has woken us up to social injustice. It has provided a stage on which we dance for each other just as the hungry and the poor danced and danced and died in Horace McCoy's 1935 Depression-era novel They Shoot Horse Don't they? Dragging their sad limbs around the floor, as a jeering public watched and screamed. Today identity is performed, displayed and proffered up for perusal, but who owns us? In 2017, Jenny Afia, a privacy lawyer and partner at Schillings law firm in London rewrote Instagram’s turgid terms & conditions as part of a study commissioned by the government: ‘Officially you own any original pictures and videos you post, but we are allowed to use them, and we can let others use them as well, anywhere around the world. Other people might pay us to use them and we will not pay you for that.’ The images we share online aren’t tethered to any sort of reality – where are they? They are jpegs floating in an impenetrable fog. We deliberately misconstrue their value because they are themselves perfectly perfunctory.

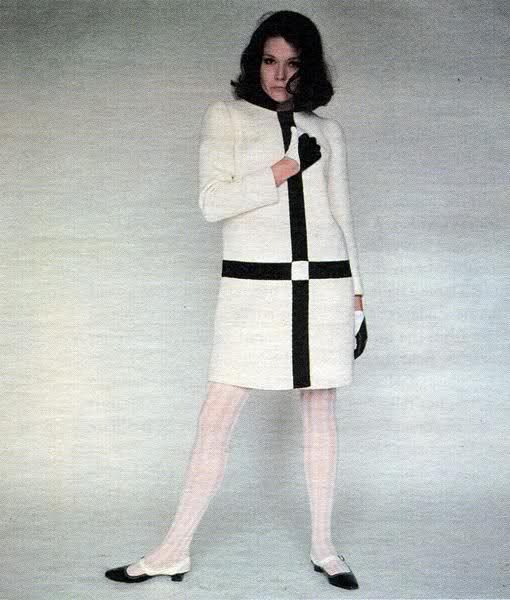

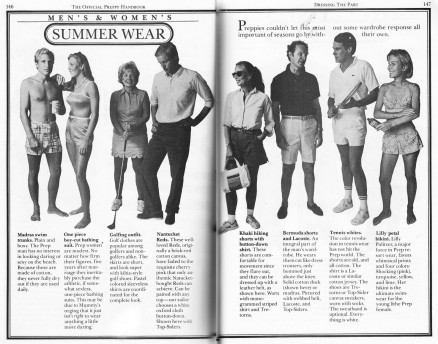

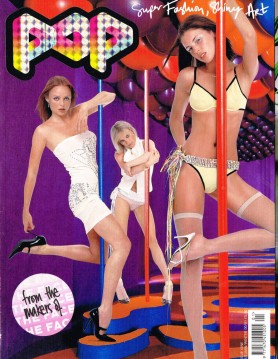

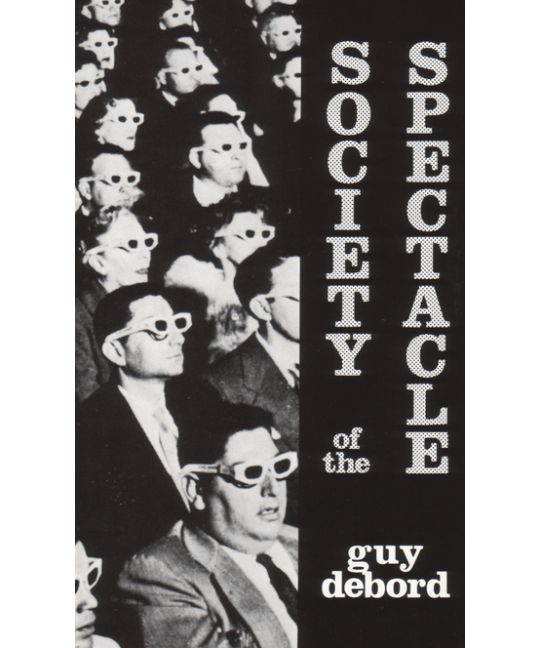

Instagram’s slutty algorithm crushes every second of life into jumbled crumbs of colour under glass. Just as theorist and philosopher Guy Debord warned about the nature of contemporary capitalism and modern culture in The Society of the Spectacle published in 1967, each of us is valued more by snapshot and less by substance: ‘The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images,’ Debord wrote. And in this re-hieroglyphic world, yellow emoji are generic to some and racist to others. Body positive selfies are stripped of any sexual subtext by a new wave of green feminism; the artist Richard Prince profits from pilfered Instagram selfies. The image is capital. Debord was writing at the exact time that Warhol made his infamous silk screen portraits of pop pin-ups Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor; Debord hoped to shake up a public dazed, confused and high on the glamour of the free market.

Today his words read as divination of our A.I. future. Each time you peer into an automated CCTV doorbell, watch your dog bored at home alone via a pet parenting app or Facetune yourself into an aged bot – you are negotiating with the world through image alone. Ten years ago, author and critic Fred Ritchin wrote:

‘The increasing cyborgization of people in which cell phones, iPods, and laptops reach near-appendage state will see photography extended into an all-day strategy ... The camera will also be circulating within our bodies and stationed in our homes, acting proactively to warn us of and possibly attempt to correct any problems (disease, fire, an accident), even on the molecular level.’

Our world may as well be on mute. The proliferation of podcasts related to visual material – to discussing art, design or film – is a glitch in the reduced role that sound plays in our world. ‘The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images,’ Debord wrote. Each of us is umpired by our own mirror image.

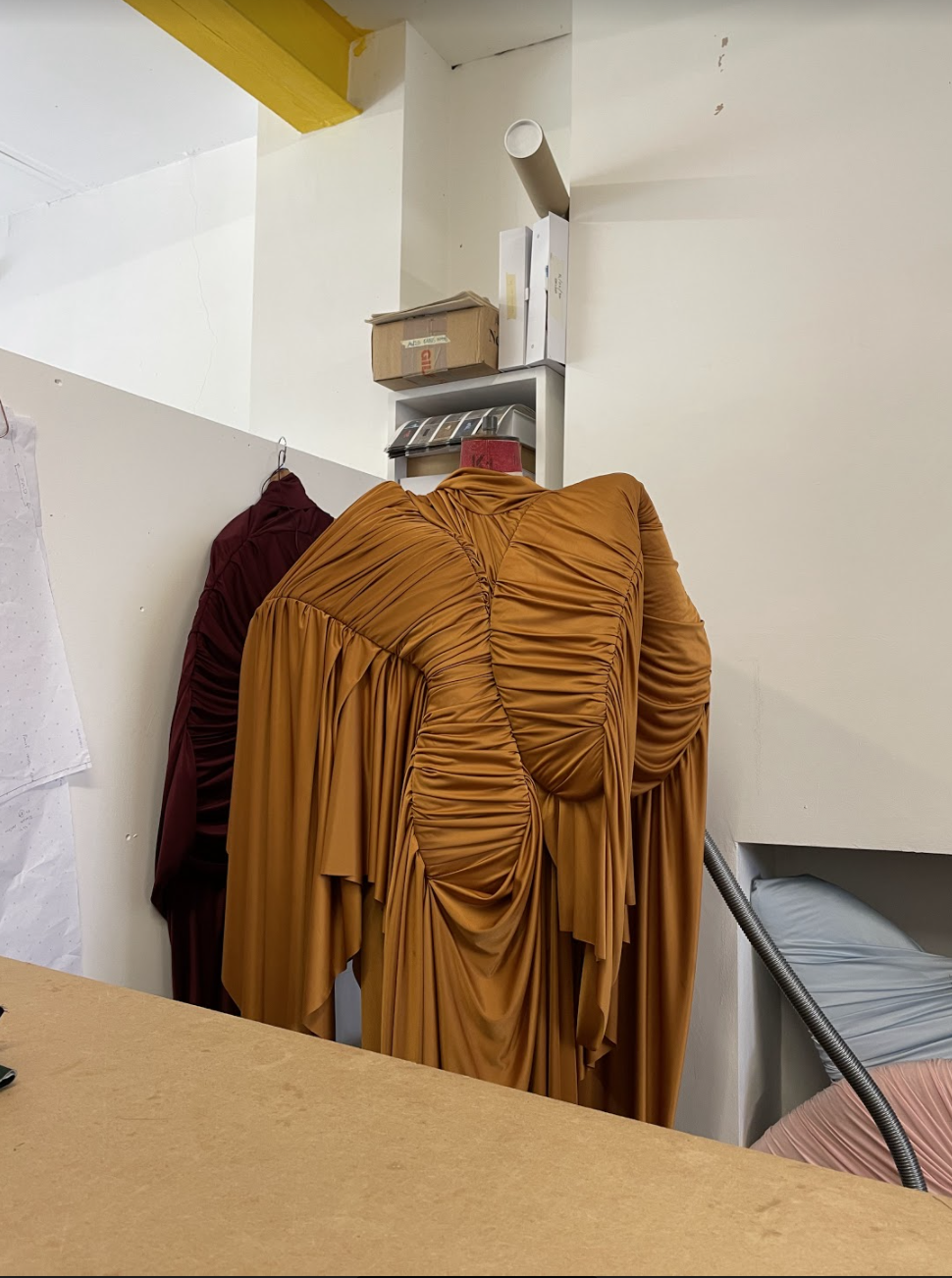

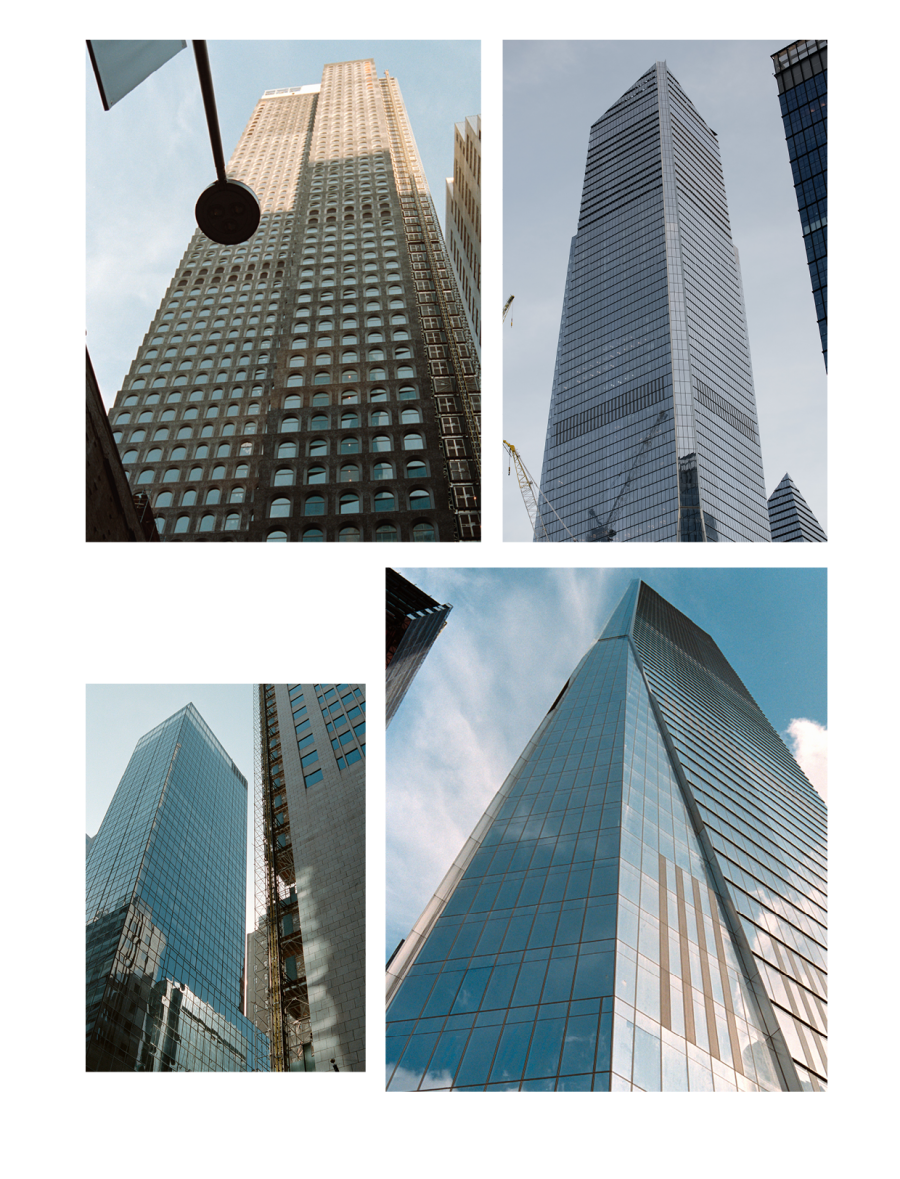

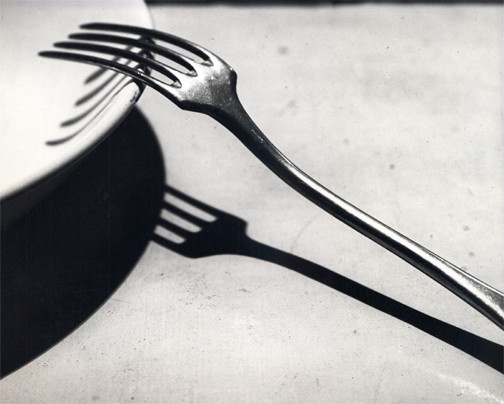

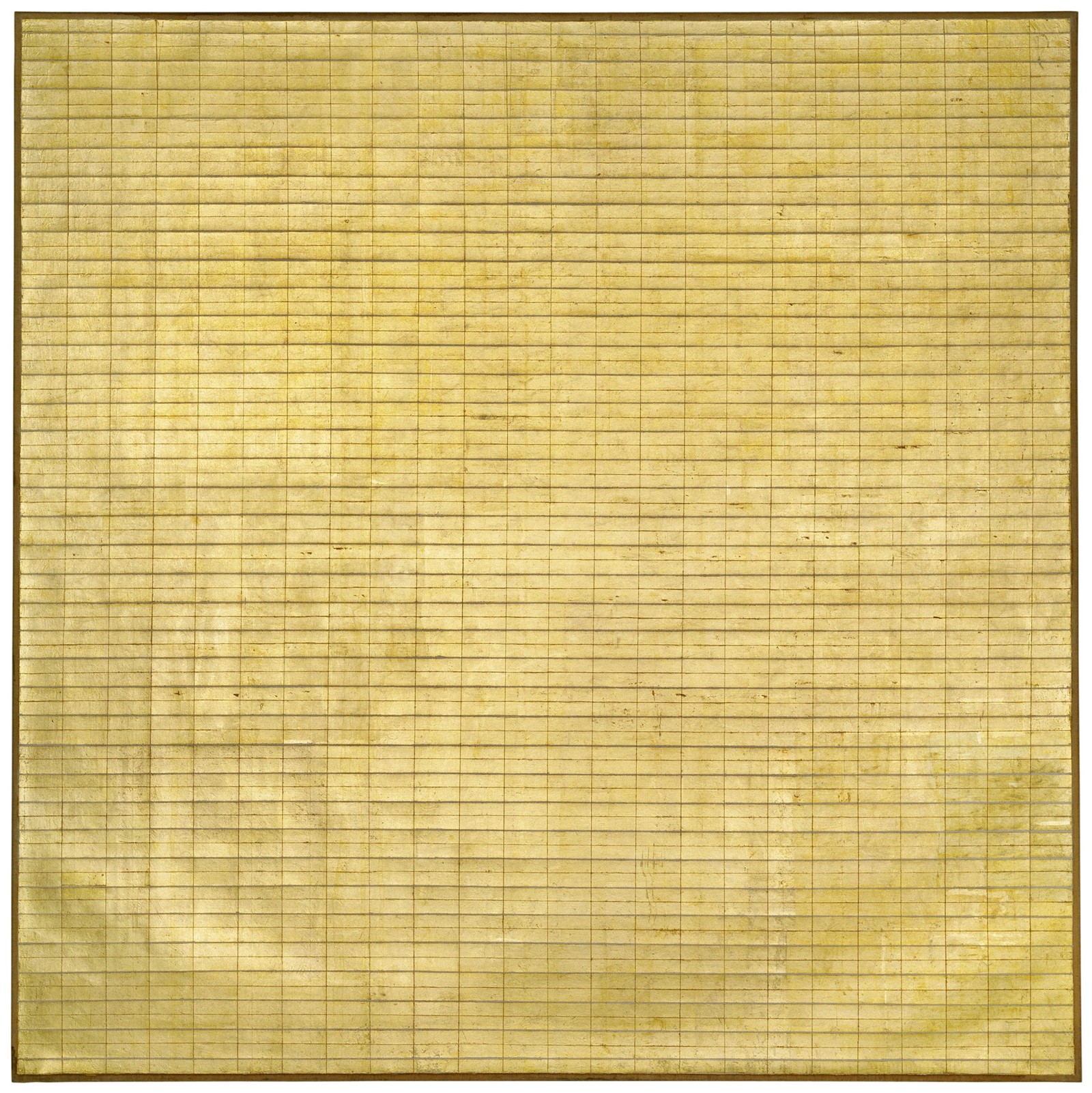

I sat and watched a 20-something take much care over the documentation of a flat white. Her brain in that moment was editing, cropping, assessing the lighting. She was art director, journalist, editor. A living, breathing, thirsty magazine, elevating a quotidian act into a vanitas still life with raw wooden table, weird hanging plants and low-slung, exposed filament light bulbs. Instagram is her canvas. This still life will slip neatly into a vortex of more complicated messages; a tapestry of ideas and problems and thighs and owls and buildings and plants and beaches and handbags and volcanoes. ‘The spectacle presents itself as something enormously positive, indisputable and inaccessible. It says nothing more than “that which appears is good, that which is good appears. The attitude which it demands in principle is passive acceptance which in fact it already obtained by its manner of appearing without reply, by its monopoly of appearance,’ Debord wrote. The uploader’s #mood doesn’t come into it.