2010

Christophe Lemaire

Published in B Magazine N°2

An interview

![Portrait by Lydia Gorges]()

![]()

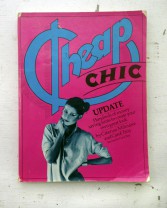

![]() Two copies of the 1970s fashion manual Cheap Chic Update, with their bright pink and yellow covers and playfully gamine, go-getter cover stars seem a little at odds in their present surroundings of Christophe Lemaire’s serene Paris showroom. The store – located in the Marais district – is replete with whitewashed wooden floorboards, cane furniture and bamboo plants, nestled in-between brands more concerned with flashy logos and fast fashion. It is clear that the designer Christophe Lemaire is often solitary in his approach to fashion.

Two copies of the 1970s fashion manual Cheap Chic Update, with their bright pink and yellow covers and playfully gamine, go-getter cover stars seem a little at odds in their present surroundings of Christophe Lemaire’s serene Paris showroom. The store – located in the Marais district – is replete with whitewashed wooden floorboards, cane furniture and bamboo plants, nestled in-between brands more concerned with flashy logos and fast fashion. It is clear that the designer Christophe Lemaire is often solitary in his approach to fashion.

Almost 20 years since starting his own label, Lemaire is still relatively unknown; embracing a level of anonymity, he says is key to his brand. Building his experience alongside Christian Lacroix and Jean Patou as well as Yves Saint Laurent and Thierry Mugler, Lemaire launched his own brand in 1991, the success of which brought the designer to melting point – Lemaire admits he was close to a breakdown.

‘I was always a bit on the side of the fashion circus,’ he says. ‘When I used to have my own fashion shows at the end of the 90s, now that

I look at it, I realise they weren’t really mature enough.’ Taking a break from his label in 2003, Lemaire focused on his role as artistic director at Lacoste. Returning in 2007, today he is self-assured, more confident and more defiant than he used to be. ‘It was a positive crisis because it was like stepping back and asking myself real questions about my motivations. I have come back much clearer in what I want to say.’

‘I was never really attracted to the star system and the whole media-obsessed fashion of

the 80s. I really think it was something that preserved fashion more than it served it,’ he reflects. Fingering his ‘bible’ – his copy

of Cheap Chic Update: the 1970s fashion guidebook he discovered after meeting its editor, Carol Troy, at a dinner in late-1980s New York, he confesses his design philosophy is in stark contrast to his beginnings. ‘Fashion for me is less of this runway culture, when I am designing, the goal is the person who will wear it. I was always more interested in creating refined and creative, wearable fashion than just images.’ Modern, working women from the actor Lauren Hutton to the photographer Ewa Rudling are immortalised on the pages of Cheap Chic Update, dissecting personal style and discussing the importance of a good white T-shirt over fad clothing – central to Lemaire’s sartorial philosophy.

A key selection of Lemaire’s work for Lacoste sits in his own store alongside his own

mens and womenswear collections – the link between the two can be validated by the fact that both are about casualwear. As Lemaire interprets it: ‘easy-wear but with style, which I find extremely now.’ The vocabulary for his brand, however, is far more complex. ‘I have to invent it. I am interested in style more than fashion, timelessness more than trends, quality in simplicity. My ultimate goal is to bring sophistication across using simplicity.’

With fanfare, a new luxury is returning to fashion: a new simplicity, a new modernity. Such obsession with purity is not new to Lemaire, always remaining faithful to his muted colour palette. He says: ‘I have a feeling that it is not just a trend, but we will have to find an evolution within that exercise because the problem with timeless fashion is it can become boring. As much as I believe in timeless fashion, I also believe in newness and evolution. There is a way to make this vision of fashion evolve with new volumes and proportions, but the philosophy behind it, I still believe, will remain pertinent.’ As he speaks, a theatrical storm hurls heavy beads of rain against the showroom window: ‘There will always be people attracted to timelessness.’

Growing up, the young Lemaire was interested in the quality of life objects could bring and was first attracted by industrial design. ‘For me, style, fashion and clothes were part of a more global interest in the stuff that surrounds us. Now I have rediscovered why I wanted to make fashion and I’m extremely clear about what I want to do.’ Lemaire talks of his clothes in a way that relates them to a kind of costume or uniform – costume to be worn for the theatre of life – it is paramount that his collections work in the everyday. ‘I can only do 50% of the job,’ he smiles. ‘It’s commonsense that style is very much linked to the person who wears the clothes. I never believed that fashion could be some style that you could buy. I can only try being as precise as possible in the way that I make clothes that will underline a personality.’

Although fluent in the romanticism of simplicity, the softly spoken designer is sentient to the risk that it could be seen as dull. ‘The problem with simplicity is that it can be very boring or poorly done,’ he agrees. ‘To get to a stage where simplicity is rich is the goal. Simplicity is more difficult to achieve than something spectacular.’

‘When you have beautiful fabric and you reduce it to the maximum essential design – you can mix it and play with it and then you can tell

your own story. I don’t believe the designer can tell you which story you can tell.’

Fascinated with the timeless nature of clothing, Lemaire’s points of reference are diverse and notably not from popular culture, which he

finds ‘actually quite ugly and uninspiring.’ He references classic Mongolian clothing with its flat patterns and deconstructed softness and a heavy focus on 1970s French glamour as inspiration. The work of Sonia Rykiel, early Calvin Klein and the designer Guy Paulin’s collections from the late 70s also provide stimulation. ‘My mother and my grandmother were very stylish, they used to wear Ted Lapidus and

Saint Laurent and what was interesting with

my mother is that she married a rich man for a while so we had quite a glamorous life. But after she divorced, we lived a normal middle-class life but even when she went though difficult times, she had a very strong sense of style.’ Growing up in Paris and Senegal impacted on Lemaire’s imagination and passion for colour.

The 1970s provides not merely childhood nostalgia for him; the characters of that era resonate too. ‘My uncle was CEO of French Vogue, so I remember when I was taking my vacations in the south of France in the summertime, he would arrive in a Jaguar with Gucci shoes and no socks and he was a party guy...it was very much of this time.’ Lemaire’s vision of this French glamour can be seen in the tranquil silhouette of a wool coat inspired by French military uniforms of the late 19th century, mixed with details from a Chinese jacket. ‘If I love Cheap Chic, I have to love the 70s!’

Antonioni’s 1972 documentary about China, Chung Kuo – Cina, is also admired by the designer, relating back to Lemaire’s awareness of uniform, his own experience being a traditional British school uniform of a navy blazer, white shirt, blue and green striped tie and grey flannels he wore at boarding school. ‘Socially, uniforms are very interesting. Of course I am not talking about dictatorship,

but I very much think that if they were more forced in schools in France, it would change the attitude a lot. I find uniforms fascinating. I love the Mao uniforms you can see in Antonioni’s movie – it’s so beautiful and interesting.”

Insight also comes from the Situationist culture of the late 1960s and the philosopher Guy Debord’s book Society of the Spectacle from 1967: a critique of contemporary consumer culture and commodity fetishism. Images, Debord said, supplanted genuine human interaction, something Lemaire felt first-hand. ‘We are conditioned in our lives to be alienated from ourselves and be stimulated by stupid things for business reasons. We

are alienated from what we should focus on – real culture is everyday culture. What we eat, what we decide to do, what we decide to read, what we decide to wear – we have to free ourselves from the culture of stupidity. I think it creates a lot of unhappiness.’

‘I hate museums and galleries, as for me, that is artificial culture; it’s a little like going to church. You go to a museum and you feel you have had your culture for the day and then you go home and watch a stupid programme on television and eat junk food.’ He smiles: ‘I’m not against junk food ... of course, I like that sometimes, but disposable culture irritates me. Bringing culture to every day – that is what I am interested in doing with my fashion.’