March 2021

Skyscraper

Published in Modern Matter N°18

Architecture and Politics

Wrapped together, stone, steel, chrome and glass become symbolic gestures of dominance, all-seeing totems to capitalism, class and charisma.

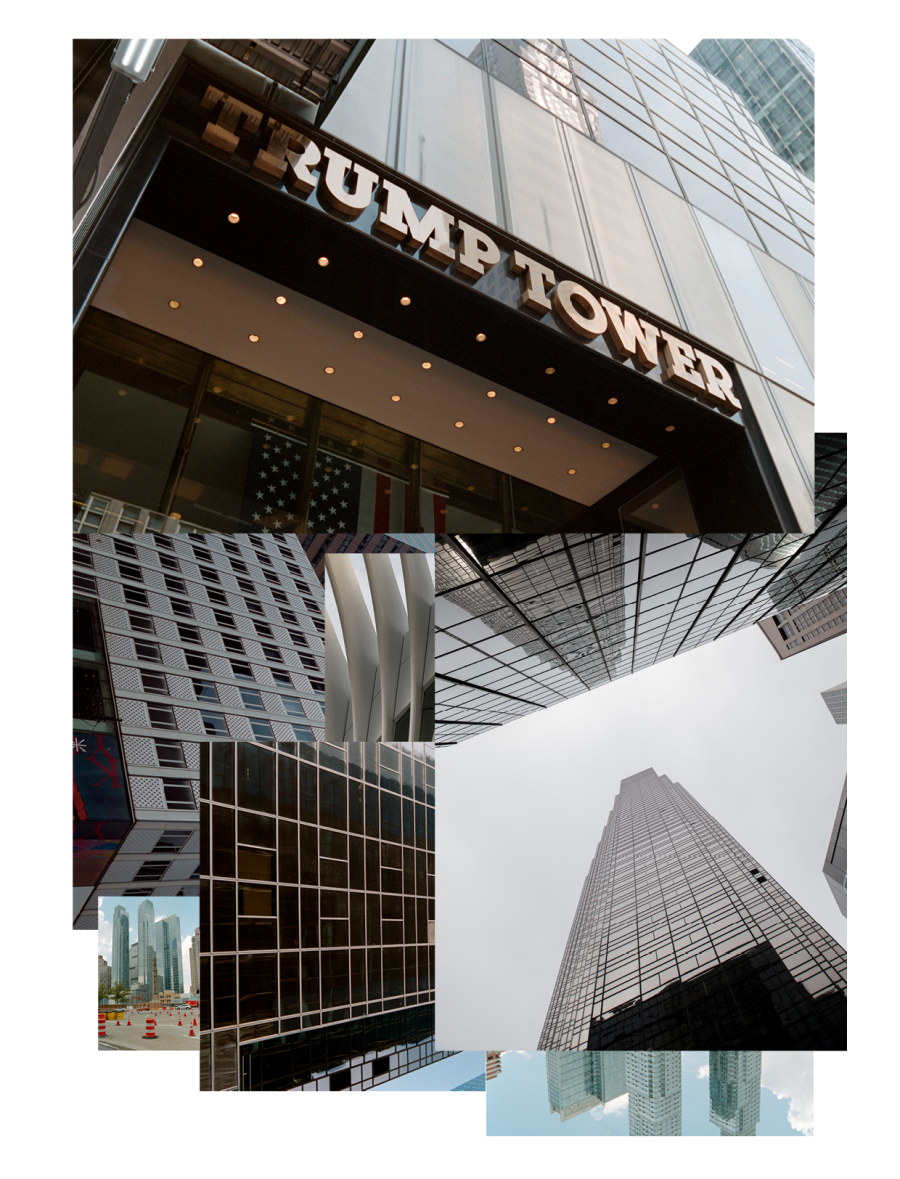

Donald Trump’s paean to high living at 721–725 Fifth Avenue between 56th and 57th Streets stands as cavalier as it did on a chilly Valentine’s Day in 1983, when its atrium and flotilla of glossy boutiques first opened to a bedazzled public. Even though a Bloomberg report last year found that the Trump Tower is now one of New York’s ‘least-desirable’ luxury buildings, its 240 tonnes of plump pink Italian limestone veined with white remain a site of pilgrimage for fans of the president’s boorish, bombastic style. An amalgam of apartments, offices and shops, its 58 floors are testament to a national ethos driven by a mania for prosperity and personal success above all: the reward of upward social mobility in return for hard graft.

Upon completion, the vertiginous living quarters once billed as ‘totally inaccessible to the public’ and meant exclusively for ‘the world’s best people,’ ignored the crime-riddled metropolis that languished far below. From his triplex dwelling, Trump could see the tops of yellow cabs, not the graffitied carts of the subway; he could look across Central Park to the north but not see its homeless; he was safe from the rising levels of crime, ‘encased’ as Trump biographer Gwenda Blair said, ‘within this bubble of serenity and privilege.’

Four gold-painted elevators still transport visitors to Trump Tower from the lobby to the higher floors, which feature a 60-foot waterfall along the eastern wall made up of geometric platforms and acidic underlighting. Tourists flock to its ‘ok nothing special’ three restaurants, leaving gushing reviews on Tripadvisor. It remains a gaudy erection of hi-gloss and nerve – a fitting backdrop for the 2012 runway debut of Kendall and Kylie Jenner who are themselves, like the skyscraper, bodacious constructions of capitalist-scented invention.

The modern city is defined by its tall buildings and the power that is wielded within them.

![Photography by Dan McMahon]()