2017

Gluck

Published in Article Magazine N°10

Singular

‘It used to annoy me when I was younger to be told continually how ‘original’ I was. What is there so original in just being oneself and speaking one’s mind?’

Born into a wealthy family in West Hampstead in 1895, the young Hannah Gluckstein was aware of the quirks that money would afford her, but was always secretive about her roots. On her 21st birthday, she used her trust fund to set up a studio in Lamorna, a small fishing village in west Cornwall then gaining fame as an artist’s colony; it was there that she first cut her hair short, and began to dress exclusively in men’s attire.

![]()

She had begun designing herself in the most radical way: ‘I am flourishing in a new garb. Intensely exciting. Everybody likes it,’ she wrote to her brother Louis in 1918. ‘I hope you will like it because I intend to wear that sort of thing always.’ She ordered shoes from John Lobb, and suits from Schiaparelli and Steibel. Her shirts were made on Jermyn Street, and she had her hair cut at Truefitt’s, the Bond Street barbers. Posing in the smart magazines of the day, she became a ‘young woman who affects pipes and plus-fours, and scorns prefixes.’ She insisted on being known only as Gluck; prints of her works were issued with the note ‘Please return in good condition to Gluck; no prefix, suffix, or quotes.’

She would go through several artistic periods — first painting formal portraits of glamorous upper-class women, and then intense, large-scale flower arrangements during a rumoured relationship with society florist Constance Spry. It was Spry who introduced Gluck to the married American socialite Nesta Obermer, who was to become Gluck’s lover and the subject of her most famous work; a double-portrait titled Medallion, which the artist referred to as the YouWe painting.

It’s a striking study of queer love. But Gluck’s work has none of the pioneering high conceptualism of Marlow Moss’s abstract reliefs from the same period; nor do her canvases have the bite of Claude Cahun’s brazen, surreal photographic self-portraits, that still seem so staggeringly avant-garde today. With their close-cropped hair and gentleman’s garb, both Moss and Cahun experimented with their sex and dress in far more radical ways. Gluck challenged convention, though, in conventional ways; her legacy is one of style.

!['Medallion (YouWe)' (1936), Gluck]()

In 1924, the American artist Romaine Brooks painted her as a young English girl, with a handsome, alabaster face. A year later, Gluck painted herself in a shirt, tie, braces and beret, smoking a cigarette. This image she made for herself, this androgyne pin-up, is confident, cocksure and classically chic.

It was an era that saw an increase in public awareness of lesbianism. The scandal caused upon the release of The Well of Loneliness (and its author’s subsequent trial for obscenity) gave a new language to the public who were both intrigued and repulsed by love between women. The distribution of photographic material was becoming more commonplace too, as depictions of multiple identities began to be seen more openly in magazines and newspapers. Gluck knew that her looks would whet appetites and break hearts; she was, after all, something of a hopeless romantic.

She largely retired from painting in the late Forties, embarking on a troubled thirty-year relationship with Edith Shackleton Heald, the first female reporter in the House of Lords. She threw herself instead into various crusades. She fought to be respected for her work, rather than her gender or family name; she patented a stacked picture frame design that became a staple of Modernist and Art Deco interiors. And she initiated a campaign for better quality paints, eventually ensuring the creation of a new standard regarding the naming and defining of pigments, cold-pressed linseed oil, and canvas from the British Standards Institution.

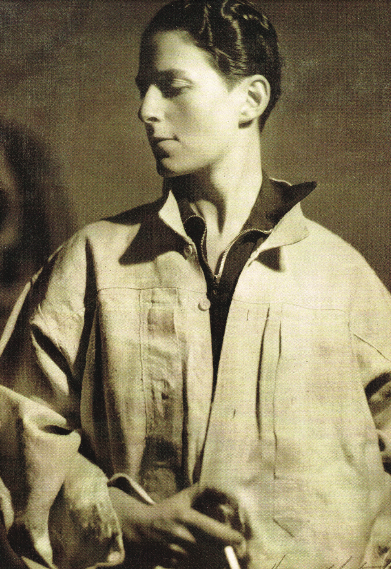

Gluck radiates a quiet majesty in this portrait of her by Howard Coster (a self-proclaimed ‘Photographer of Men’), taken when she was 31. In it, she is Orlando; at once masculine and feminine, buttoned-up and unzipped. Bathed in light, her hair is glossy, her neck unadorned. There is a slight knowing curve of the mouth.

Ultimately, Gluck’s style is more powerful than either her orientation or her art: ‘I just don’t like women’s clothes,’ she declared. ‘I don’t object to them on other women... but for myself, I won’t have them... I’ve experienced the freedom of men’s attire, and now it would be impossible for me to live in skirts.’

Almost a century ago, one newspaper dubbed her ‘ultra- modern.’ And today we’re still struck by the timeless cut of Gluck’s jib, with its impervious, impenetrable elegance. The high-priestess of lesbian chic, she foretold the power of a good look.